Education in the McDougall Street Corridor

By Willow Key

For Black settlers, education was a means of social mobility and racial uplift. As the McDougall Street Corridor emerged in the mid-nineteenth century, the Black community in Windsor set their sights on founding institutions that would facilitate this most fundamental aspect of citizenship and freedom, the education of both children and adults.

As early as 1851, Mary Ann Shadd Cary, a prominent abolitionist and educator, established an integrated school in the former military barracks on the site of what would become Windsor’s civic square. Recognizing the desperate need for education amongst newly settled freedom seekers, she worked tirelessly to provide men, women, and children of the Corridor with fair and accessible education. Though Cary’s school was short lived, closing in 1853 due to limited funding, her work set in motion a long history of activism regarding Windsor’s Black community and access to quality education.

Institutions like Cary’s were necessary during this period of settlement as many schools in Ontario were racially segregated, a practice legalised through the Separate Schools Clause, an amendment to the Common Schools Act of 1850. The clause supported the legal segregation of children on the basis of race and religion, allowing school boards to deny entry to Black students and for white taxpayers to demand that Black students be excluded from white schools. This placed the responsibility of establishing schools for Black children not on the municipality or local school board, but on the Black community itself. While some residents of the McDougall Street Corridor fought against these discriminatory laws, others created their own schools, often with limited funding and resources. Another abolitionist and educator, Mary E. Bibb, opened an integrated private school in Windsor not long after Cary’s, where she taught mostly Black students for at least a decade.

Education was also provided by religious institutions. Sunday Schools and bible study served as an opportunity for the church to aid in the development of fundamental skills such as literacy amongst adults and children. Black education was an essential part of church life, where many adults and children learned to read and write in the process of studying religious texts. Canada’s first Black Roman Catholic mission, the Catholic Coloured Mission of Windsor, was established in 1887 by Reverend James T. Wagner. Operating for six years, the Coloured Mission was originally located in St. Alphonsus Hall, the original frame building at Goyeau Street and Park Street East. The mission school managed to enrol ninety-three students during its operation, providing education to orphans and poverty-stricken children in the area until the school closed in 1893.

The Corridor’s first official segregated public school was located in a tiny brick building on Assumption, near McDougall Street. Referred to as the St. George Coloured School, this institution was among the first public schools in the city. Following the establishment of the Separate Schools Act the city of Windsor set out to establish three public schools, a Common School or Protestant school, a separate Roman Catholic school, and a coloured school. Black students were educated in a rented shed until a proper building was erected. The St. George School opened in 1862 and operated for nearly thirty years, hiring Black educators from within the community like Mr. Nero and Mrs. Louise Williams to oversee the education of approximately one-hundred and fifty children.

It took nearly a decade for the school to receive a much-needed addition to accommodate their rapidly increasing student body. The delay in building this addition and the numerous unanswered pleas, not only from parents but also school board trustee J. C. Patterson, highlights the unfortunate conditions Black students and educators faced until an extension was added in the late 1870s.

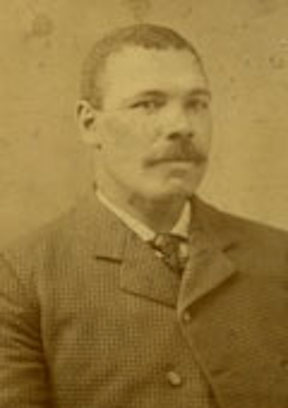

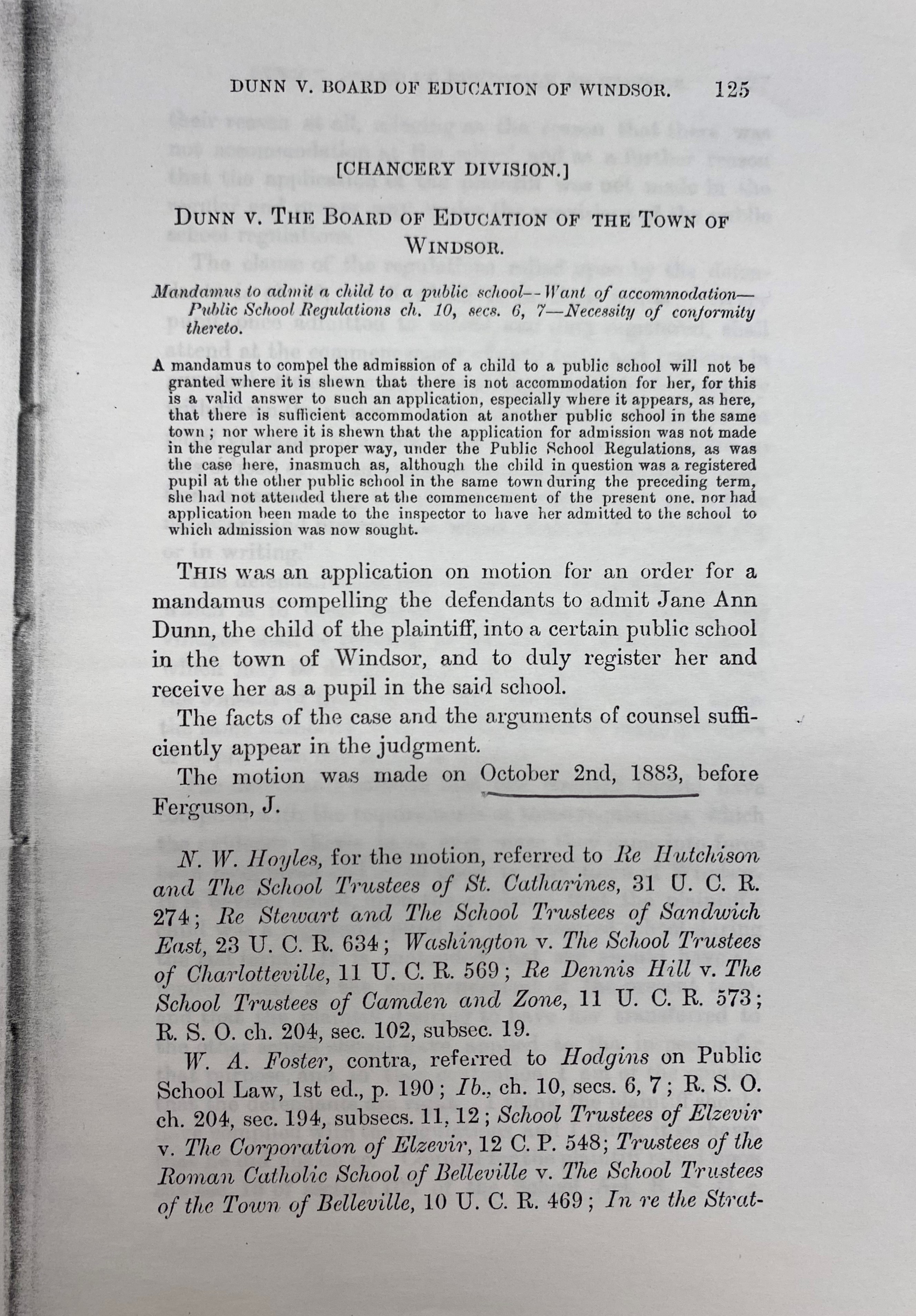

The St. George School closed in 1888 at the decision of the trustees, citing the fact that students should be educated in integrated classes. This decision came on the heels of the Dunn v. The Board of Education of the Town of Windsor case of 1883 in which prominent businessman and later Alderman James L. Dunn, dissatisfied with the overcrowding and segregated St. George School, attempted to enrol his daughter, Jane Ann, into the Public Central School. Citing limited accommodations, the Public Central School turned Jane away. Dunn challenged the school’s decision and their cited reasoning in court, arguing that Jane was denied entrance due to her race. The court later supported the Public Central School by stating “there is sufficient accommodation at another public school [St. George] in the same town,” and calling attention to the existing school regulations,

Pupils in cities, towns, and villages shall be required to attend any particular school which may be designated for them by the inspector, with the consent of the trustees. And the inspector alone, under the same authority, shall have the power to make transfers of pupils from one school to another.

The court argued though St. George was “a coloured school [it] is not a separate school,” insinuating that Dunn had no legitimate reason to be disgruntled. Dunn lost his case, but sparked discussion amongst parents of the Corridor. By the end of the decade, it appears that many other Black residents threatened legal action against the segregation of their children, ultimately forcing the city of Windsor to finally admit Black children to the city’s common schools. The court case can be read by clicking this link.

Dunn’s contributions toward education equality were recognized in 2022 with the opening of the James L. Dunn Public School at 1167 Mercer Street.

Not long after Dunn’s court challenge, the city invested in several new public schools, including one on Mercer Street in the heart of the McDougall Street Corridor. Opening in 1891, the Mercer Street School was attended predominantly by Black students from the area. By 1902, it was expected that all children of the Third Ward would attend the school. However, anti-Black racism resulted in Mercer Street School maintaining a predominantly Black, Jewish, and Eastern European population.

It was estimated that around 300 Black students were enrolled in public schools in Windsor by the early twentieth century, with the majority attending Mercer Street. For Black educators like Ada Kelly Whitney, Ann Smith Benson, and Eunice Hyatt Kersey, Mercer Street School provided an opportunity to invest in the future of their community as well as secure long-term employment.

Mercer Street School operated for fifty-five years until the building was partially damaged by arsonists in June of 1946. Shortly after the fire, it was determined that the school would permanently close, sending more than two hundred students and six teachers to other schools across Windsor.

The grounds of Mercer Street School were used as a training site by police and fire services for a time, and later a temporary location for St. Clair College. Today, the Brighton Court apartment complex stands in the place where bright minds of the McDougall Street Corridor were once educated.

Other schools commonly attended by Black students following desegregation included Dougall Avenue Public School, Frank W. Begley Public School, Queen Victoria Public School, Prince Edward Public School, J. C. Patterson Collegiate Institute, and W. D. Lowe Vocational School.

While the report on “The Position of Negroes, Chinese and Italians in the Social Structure of Windsor, Ontario” (1965) suggested “there is little racial discrimination in the educational field,” oral histories collected for this project suggest otherwise. Our interviewees revealed that racial discrimination was present in many of Windsor’s public schools well into the 1980s. Former students recalled numerous occasions when they experienced or witnessed acts of prejudice by educators. In many cases, interviewees stated their primary experiences with discrimination occurred while attending Windsor public schools. Black students (typically young men) were often encouraged to seek training in the trades rather than apply for post-secondary education, even when they were academically capable. When expressing their desires to pursue a particular occupation or field of study, Black students were often met with alternatives from teachers and guidance counsellors. As one interviewee recalls,

I know my brother was told “oh you’ll never be more than a janitor” when he was in high school. When someone is telling you that over and over and over again, and you know he did, he struggled a bit with school, but instead of finding the best way for him to learn, it was just like “no, you’ll never do anything more.”

Additionally, they recalled,

very few Blacks in the graduating class from grade thirteen, most took the route through grade twelve and definitely were encouraged to do that by guidance counsellors. You know, when I said what I wanted to do, I was encouraged to take a different route… I knew, probably from the time I was four or five, I knew I was going to be a teacher.

For others, it was common to hear racially insensitive language from teachers or fellow students,

And there was a lot of, like comments that were made to me in high school. I remember this one. I'll never forget it. He had said: “All they did in Africa was swing from trees.” A teacher said that… that comment has never left me, and I remember going home and telling my dad about it.

Another interviewee told us,

my sister remembers saying to her teacher: “Miss, so and so called me the N word” and the teacher said to her “well, you are.” That was her response. She can remember the teacher giving out valentines or whatever, and she wouldn’t get one from the teacher.

Even for the highest of academic achievers, discrimination was impossible to avoid. Dr. Philip Alexander recalled being selected, along with several other top maths students at J. C. Patterson, for an interview with a local accounting firm. However, after being selected he was quickly turned away, deemed to be “not the right fit.” Philip had achieved the highest standing in the province for the optional extra mathematics competition, but it was suggested he apply to a Black firm in Detroit instead.

The quality of education at certain schools also positioned Black students at a disadvantage. By the 1960s, some schools like W. D. Lowe operated compensatory programs in which students were assumed to possess low educational abilities and were often taught and graded on an easier scale. It was not uncommon for Black students to be funnelled into these programs regardless of their academic abilities.

While many residents have shared fond memories of their time as students, race-based inequality in Windsor’s schools was commonplace and detrimental for many students, especially when students were discouraged from reaching their fullest potential academically. But Black students chose to persevere, demonstrating their brilliance and fortitude by being successful graduates and upstanding citizens. The Corridor produced numerous educators, including Lois Larkin, Nancy Allen, and Cherie Steele Sexton. In many ways, their experiences in Windsor Public Schools motivated them to pursue careers in education and provide the support that had so often been denied to them.