Urban Renewal and the Legacy of Black Uprooting

By Willow Key

A central component to recovering the stories of the McDougall Street Corridor is understanding the history and impact of postwar urban renewal policies.

Urban renewal is the process by which tracts of land in urban areas are cleared for the purposes of slum removal and redevelopment. Urban spaces that experience renewal are most often transformed from working-class, single-family housing to either middle-class housing and private development or government projects.

Often, high-density public housing and apartment complexes are erected (ideally in close proximity, but this is not always the case), to accommodate the housing needs of those who were displaced. This process of urban transformation has long been conducted without the consent or responsible consultation of the affected communities and as a result residents have been pushed out of their homes, many have lost businesses and, in some cases individuals experienced forced removals.

The rise of urban renewal as a popular postwar policy stemmed from governmental concerns with overcrowding in urban centres as a result of anticipated population growth following World War II (1939-1945). This concern was exacerbated by Canada’s existing housing crisis and the advanced age of most of the country’s urban housing stock. Interest in modernizing cities and ensuring the best use of urban land was also a factor in the desire for urban renewal.

Under the National Housing Act, the Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation would assess municipal plans for redevelopment and if they were approved, cities could receive up to 75% of their renewal funding from the federal and provincial governments beginning in the early 1950s. As urban renewal became increasingly popular with municipal governments, renewal policies and funding continued to expand well into the next decade.

While the redevelopment project of the 1960s was responsible for dramatic changes to the McDougall Street Corridor, it was in fact part of an ongoing process of uprooting residents and businesses of Windsor’s original Black district.

By the turn of the twentieth century, much of the northern portion of the Corridor was heavily populated by African Canadians. Slowly over the next few decades, various industries like the McLean Lumber Co., O. P. Hamlin Co. Ltd., an auto wreckers’ yard, and a cold storage facility pushed these residents further south, past Wyandotte Street. By the time of the postwar urban renewal project, some blocks within the Corridor had already lost homes and businesses significant to the Black community.

Urban Renewal Planning in Windsor’s Downtown Core

Windsor’s central redevelopment project began in 1959 and covered 23 blocks within the downtown core.

Three downtown neighbourhoods were chosen for redevelopment, with “Redevelopment Area I” covering the northern portion of the McDougall Street Corridor neighbourhood and totalling approximately 22 acres bound by McDougall Street to the west, University Avenue to the north, Glengarry Street to the east, and Wyandotte Street East to the south.

For the Black community, this area was home to both the British Methodist Episcopal and Tanner African Methodist Episcopal churches, the Walker House Hotel, Landrum Hall and the Frontier Social Club, numerous other businesses, and an estimated 35 “coloured” households by 1958.

Deemed by urban planners to be the centre of blight and low-income housing, the Corridor's redevelopment was considered of the utmost importance to facilitating a more tourist friendly downtown core. Plans for the area focused on providing residents with multi-family housing in the form of public housing with the remaining land being used to expand municipal facilities and parking.

J. Lewis Robinson, founding head of the geography department at the University of British Columbia, conducted a study of Windsor’s urban geography in 1942. Robinson refers to the “negro section of Windsor” as a slum, extending along McDougall Street and Windsor Avenue. He concludes in his report:

This section has been the home of the negroes since they first escaped across to the freedom of Canada, and has always been decadent. Small houses, in poor repair, with few services, make up the centre of the third-class zone.

This was a common perspective and one that greatly benefited those members of city council who were interested in seeing the redevelopment of the area for more economically rewarding opportunities. Language used to describe the community was paternalistic in nature, as were the policies of urban renewal. Arguments for the health and safety of residents were bolstered by progressive policies built around models of social development and modernity, suggesting it was in the best interest of residents for their community to be razed and uprooted.

Certainly, some homes in the McDougall Street Corridor were in rough shape and needed to be razed. However, most homes were in fair condition.

Survey data collected by Windsor’s Planning and Urban Renewal department in 1958 suggest at least 80% of survey participants were satisfied with their current living conditions and the conditions of the area, noting the importance placed on “sentimental associations and proximity to services, transportation, the market and downtown shopping.”

The Effects of Urban Renewal on the McDougall Street Corridor

The impact of expropriation in the McDougall Street Corridor community was significant and devastating.

Census records suggest the population of all three redevelopment areas dropped by almost 30% between 1956 and 1961. Of course, factors contributing to this decline are not solely the result of uprooting. Suburbanization and the desegregation of other parts of the city contributed to both Black residents, and other minority groups, moving out of the area during this period.

Compensation for expropriated homes can be described as fair at best. For residents being forced to give over their main financial asset to urban planning, compensation for lost homes and properties were typically dispensed according to the fair market value, often based on the highest and best use of the property rather than the cost of property loss, the emotional or physical toll of uprooting, or the costs associated with having to relocate.

In 1961, McDougall Street Corridor resident, Mrs. Rose Timbers, was recorded as feeling “bitterly about the necessity of her displacement and is demanding $14,000 for the old frame residence,” she owned at 277 University Avenue. Land records show similar sized properties in the area received as much as three times that amount in compensation. The Timbers’ home was compensated $11,600 in 1961.

To make matters worse, for many Black residents, the news of redevelopment and the razing of their community was unanticipated. Some interviewees indicated that communication between the city and Black residents was limited, with many residents unaware of the full scope of the redevelopment project until much of the area had already been demolished.

The effects of urban renewal on Black land ownership in the area is significant also. Land registry documents attest to the common presence of Black home ownership in the McDougall Street Corridor until the early 1960s. For more than a century, the importance of homeownership was written in the margins of land registry documents as homes and businesses were passed on to children, grandchildren, and close family and friends for “Love and $1.00.”

Another issue residents faced following redevelopment was access to public housing or alternative accommodations. Compared to the city wide average, families within the Corridor were 2-4 times larger. The standard nuclear family scheme of most public housing units made it impossible to re-house large, multigenerational families, especially those of fixed or limited incomes. Data collected by the Urban Planning department suggests that of those residents surveyed in 1958, 40% required three or more bedrooms if they were to be made to relocate.

The public housing and apartments that replaced these multi-generational homes could not accommodate the large, extended families that were common within the Corridor and as a result, many families left for newly desegregated neighbourhoods in other parts of the city, and some moved to Detroit or other cities in the province.

Moving, however, was not as easy for Black Windsorites as the Planning and Urban Renewal department had assumed. The McDougall Street Corridor emerged as a result of anti-Black racism and housing discrimination. The presence of racially restrictive covenants meant that Black Windsorites, as well as other visible minorities, struggled with finding suitable accommodations in most neighbourhoods throughout the city. This was no different after the expropriation. A number of interviewees shared how some families had non-Black friends inquire and, in some cases, purchase homes for them in areas that often discriminated against ethnic minorities.

In addition to racial discrimination, housing in Windsor was still limited by the early 1960s. In 1948, Windsor’s mayor, Arthur J. Reaume, spoke to the ongoing housing crisis, stating “...housing in Windsor is now more acute than it has ever been,” and suggesting that 3,500 people “are living in quarters not fit for human occupancy.” An article from The Windsor Star that same year spoke to this dire situation when the Windsor Board of Control considered the possibility of utilising the retired Mercer Street School building as a site for families waiting for housing. This came on the heels of families being housed in the former Louis Avenue School.

Much of the three redevelopment areas of the downtown core had been cleared by 1964, yet the demand for housing continued to rise. Even with the momentary decline in population and the introduction of a massive public housing complex, multiple apartment buildings, and more on the way, accommodations for former residents of the area and those moving into the area were in short supply.

Redevelopment projects in the McDougall Street Corridor continued into the later part of the twentieth century. From Goyeau Street to Howard Avenue, between Wyandotte Street East and Erie Street East, various blocks of the neighbourhood succumbed to renewal projects that saw J.C. Patterson Collegiate, the old Mercer Street School, the North American Masonic Lodge No. 11, and dozens of homes razed to make way for the Brighton Court apartments, MacDonell Manor, Agnes MacPhail Manor, the Windsor Essex Community Housing Corporation, the Land Registry Office, and the Ministry of Community and Social Services building.

Yet, by the end of the 1970s, it seemed all hope had been lost for the fervour that once surrounded urban planning and redevelopment. The introduction of Devonshire Mall and the closure of landmarks like Smith’s department store; Bartlet, MacDonald and Gow; and the massive Steinberg’s Grocery and Department Store, felt like the death knell of Windsor’s downtown core and certainly a roadblock to the retail tourist hub Windsor’s urban planning department had anticipated.

The proposed waterfront hotel had yet to be erected at Riverside Drive and Church Street, and many sites cleared for development in the 1960s were transformed into parking lots for the time being. By 1980, The Windsor Star was reporting the disappearance of single-family homes and the dissolution of the downtown residential communities as the impact of 1960s redevelopment, suburbanization, and industrial and manufacturing decentralization became increasingly clear. Urban planning reports from the mid-1970s suggested much of the downtown core was still in a state of structural and economic decline. Of course, early urban planning failed to acknowledge the changing patterns of Windsor’s downtown core, focusing on superficial changes, land clearance and development and assuming private developers would flock at the opportunity of vacant land.

Windsor’s urban planners ignored the contributions made by local businesses, both formal and informal, the importance of community, and the role the McDougall Street Corridor, and other neighbourhoods, played in keeping downtown Windsor teeming with life.

Ethnic Minorities and Urban Renewal Planning

The McDougall Street Corridor was not the only community to experience the effects of the city’s urban renewal project. Canadians of Chinese, Eastern European, Italian, and Jewish ancestry had established their own communities in the downtown core by the late nineteenth century.

Windsor’s historic Chinatown, bound approximately by Riverside Drive East to the north, Goyeau to the west, McDougall to the east, and University to the south, emerged in the 1890s and was home to numerous businesses and heritage clubs. On the heels of the McDougall Street Corridor expropriation, the Chinese community experienced a similar blow when the city designated this neighbourhood as Redevelopment Area II. The construction of Le Goyeau Apartment complex, the creation of the Civic Green, and the clearance of land for private development saw the destruction of multiple blocks of Windsor’s Chinatown by the mid 1960s. Businesses and community spaces such as Shanghai Tavern, the Chinese Benevolent Association, and Sam Sing’s Laundry on Pitt Street were lost, along with family homes and sentimental spaces. It is important that this community, too, receives recognition of its contributions to the success of Windsor’s downtown, and the immense loss they experienced as a result of renewal.

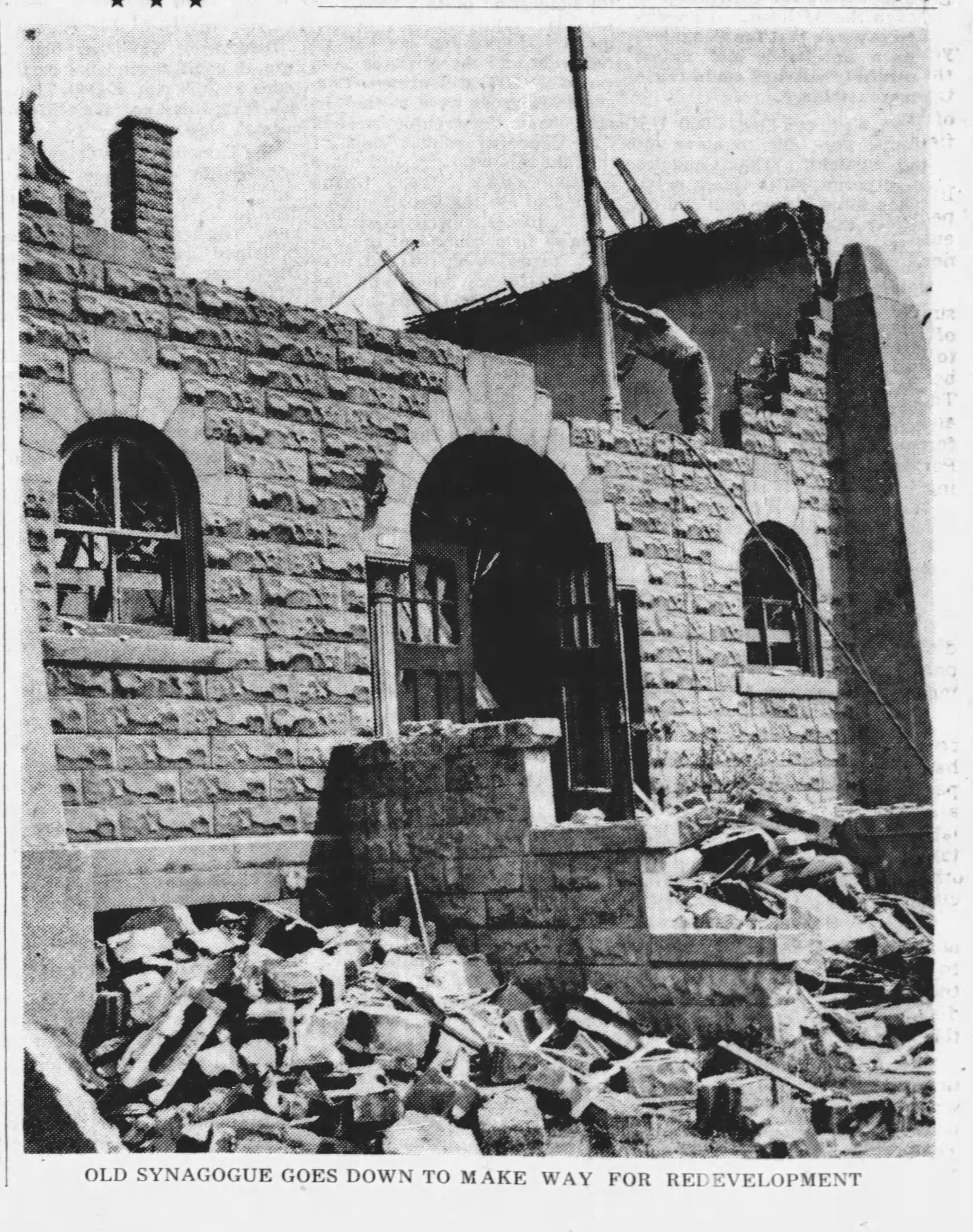

In the late-nineteenth century, Windsor’s Jewish population resided primarily in the downtown core, with many families living and intermingling with residents of the McDougall Street Corridor and Chinatown. Like Black and Chinese Windsorites, Jewish residents were restricted to the downtown core by racially restrictive covenants. Much of the Jewish business district surrounded the city’s market, with prominent families like the Meretskys and the Kovinskys investing in a permanent community by purchasing and renting land in the area to Jewish immigrants. Like Black residents, Jewish Windsorites participated in both formal and informal economies, with numerous businesses, market vendors, and individuals providing much needed services for those living in the downtown core. By the urban renewal era, much of the Jewish community had moved further south toward Giles Avenue, though some historic locations like Shaarey Zedek Synagogue, located on Mercer Street, were expropriated for the purposes of public housing.

Across Canada, minority communities found their neighbourhoods at the centre of postwar urban renewal projects. Of course, those were also communities that historically were denied access to other residential areas and limited in their economic and social opportunities.

The impact of urban renewal on ethnic minority communities was so common, the 1959 Urban Renewal Seminar organised by the Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), included these comments from E. A. Levin, of the Architectural and Planning Division of the CMHC:

The first of these [difficulties] is the fact that these small out-groups have their own characteristic folkways, which are inevitably threatened by redevelopment, and the group therefore resist the proposals. A simple example can be taken from Vancouver where a significant number of single Chinese men are found in the proposed redevelopment areas. These men live in Tong houses, a type of accommodation the equivalent of which cannot be provided under the National Housing Act… Windsor, which has both Negro and Oriental minority groups, and Halifax which has a Negro minority group, both face problems of this or a similar kind.

Additionally, experts recognized the “cultural facilities such as churches, clubs and meeting places” that would not only be destroyed by urban renewal, but would most likely be too expensive for community members to reproduce elsewhere. Postwar urban renewal impacted these cultural groups significantly as expropriation and demolition meant difficulties in finding non-restrictive accommodations and finding replacements for work in informal or community-based economies. These are elements that are not often considered when discussing the impact of urban renewal. For many, urban renewal was not simply an inconvenient move from one location to another, it was quite literally the destruction of livelihoods, social and familial bonds, heritage, wealth, and opportunity.

Regardless of the acknowledged negative impact urban renewal posed to these vulnerable communities, cultural districts and neighbourhoods across the country lost religious spaces, community centres, businesses, schools, homes, and historic sites, so cities could put urban spaces to “better use.”