Political Engagement, Civil Rights, and Activism

By Willow Key

As seen throughout this digital exhibit, anti-Black racism played a role in every facet of life for residents of the McDougall Street Corridor. Every club, organisation, and church in the neighbourhood battled racial discrimination and segregation within the city. These institutions worked together to address the varied needs of the community and combat unfair treatment.

However, there were three Windsor-based organisations that were successful in influencing local and provincial civil and human rights legislation: the Central Citizen’s Association, the Windsor Interracial Council, and the Guardian Club.

Early activism in the Corridor was championed by church leaders and members of Black fraternal orders. Men like James L. Dunn, Robert L. Dunn, and Isaac Nolan were among the first Black aldermen in the city. These men utilised their experience in community leadership and social activism to assume positions of power in Windsor’s third ward.

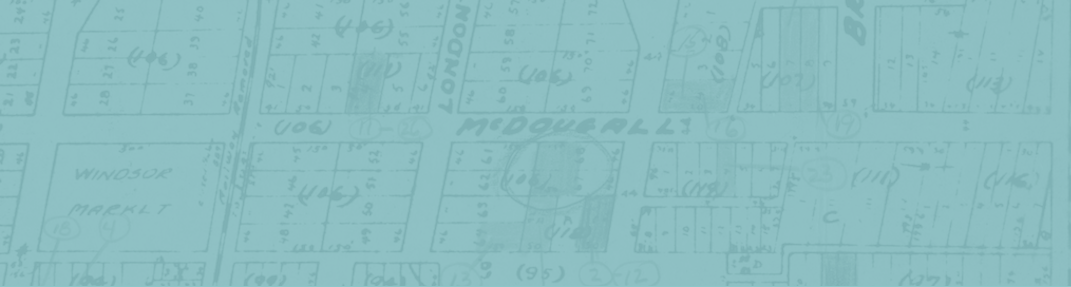

The Central Citizens’ Association

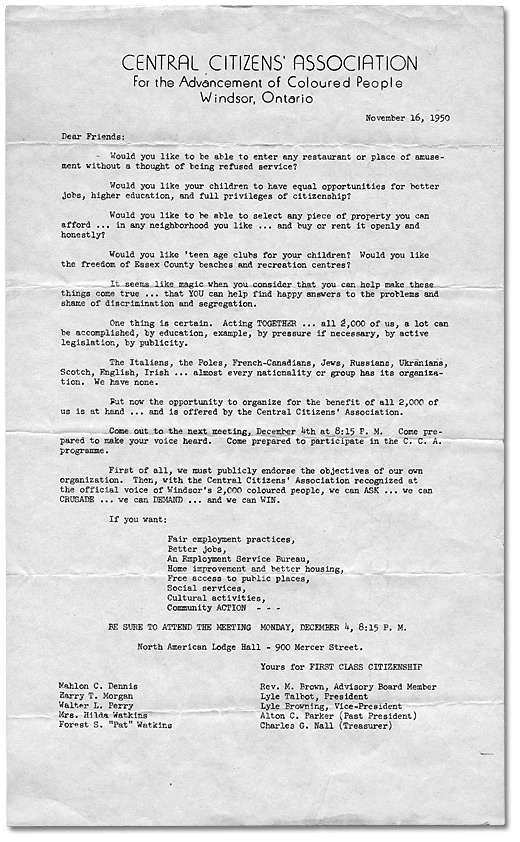

It’s no surprise some of these men, and many other community leaders, would play a role in creating Windsor’s first civil rights organisation, the Coloured Citizens’ Association (CCA). The association was established in 1928 when church leaders Reverend Arthur R. James, Rev. I. H. Edwards, and Rev. F. O. Stewart met to discuss the racial discrimination facing their people and possible modes of improvement.

CCA records cite the immediate need “of organising our people as a civic unit in order to protect and develop our interests” as the motivating factor for the association's beginnings. Following this meeting, numerous prominent and civic-minded residents of the Corridor enlisted as members of the association, with membership steadily climbing to three hundred by 1940. The CCA maintained its position as the “official voice of the coloured people of Windsor in all matters” that affected the community as a whole.

By the late 1930s, the association would be renamed the Central Citizens' Association for the Advancement of Coloured People. Three decades before the province established the Human Rights Commission, the CCA worked tirelessly to address discrimination in all sectors of Canadian life, focusing primarily on “fair employment practices legislation; more employment opportunities for colored people; home improvements and the elimination of racial segregation in housing and the end of discrimination in public places such as hotels, taverns, restaurants and resorts.”

Networking through their monthly meetings, the CCA invited Black leaders and those sympathetic to the plight of Black Canadians to speak on various topics from education, advocacy, and politics. Guest speakers included the director of the Detroit Urban League, the manager of the Brewster Homes Detroit (the first federally funded housing project for African Americans which was located in the former Black Bottom neighbourhood) and the executive secretary of the Y.M.C.A. Detroit. This Y.M.C.A Detroit meeting followed the CCA’s struggle with Windsor’s Y.M.C.A. and the attempt to establish a separate community centre by some members of the Black community after reports of discrimination against Black youth emerged. The Science, Arts and Crafts Club, a youth auxiliary of the CCA, rejected the proposition of a segregated centre, instead working to fully integrate the Windsor Y.M.C.A. This youth offshoot was invaluable in preparing a new generation of McDougall Street Corridor activists.

The association held membership drives and meetings at local spaces including Landrum Hall, the Masonic Lodge on Mercer Street, and the B.M.E Church. Political meetings were also held at Landrum Hall in which municipal candidates in the Third Ward listened and engaged with the CCA as well as residents. With the Black population in Windsor making up a significant percentage of those constituents in the third Ward, politicians quickly understood that addressing the concerns of organisations like the CCA was necessary to secure the much-needed Black vote between the 1920s and 1950s.

The CCA also worked to increase Black political representation by placing candidates in positions of influence. In 1931, the CCA supported member Dr. Henry D. Taylor’s election to the Windsor Board of Education, with Taylor succeeding and maintaining his position for more than thirty years. Another attempt in 1940 to elect William Bush as city alderman for the third ward was unsuccessful.

Additionally, the CCA established a program to encourage residents to apply for jobs with the city or in industries that had few Black employees. CCA secretary Ethel Christian provided aid by researching job requirements and examinations for those seeking to apply. It was through the work of the CCA that Windsor’s first Black uniformed police officer, Alton C. Parker obtained his position in 1942. The association was instrumental in changing local policies and influencing businesses and industries to hire more Black workers, with letters being sent to the Norton Palmer Hotel, Windsor Packers Limited, and Purity Diary. While many successful placements were made across the city, some businesses “flatly refused” including Dominion and M&P grocery chains. In 1932, the CCA considered boycotting both stores in response.

The CCA’s advocacy was not limited to the McDougall Street Corridor. The association was also dedicated to forging relationships with other activist groups in the city. In 1938, the CCA participated in the Conference on the Padlock Law and Civil Liberties, held at the Norton Palmer Hotel. The year before, Quebec Premier Maurice Duplessis established the Padlock Law, enabling the lawful closure of any operations or meeting spaces deemed to be in support of communism. The law did not define communism, making its use subject to the discretion of law enforcement. For organisations like the CCA, the Jewish National Workers’ Alliance, and the Essex County Trades and Labour Council, the Padlock Law served as a reminder that their pursuits for lawful organising and free speech were in jeopardy if the law were to be adopted in the Province of Ontario.

It was also clear that Windsor’s city councillors were divided on publicly supporting anti-Padlock Law proposals. In response, delegates representing more than twenty local organisations consisting of trade unions and workers’ rights groups, civil rights groups, cultural community organisations, and religious institutions, all pledged support for a petition against a law they deemed fascist in nature.

Other activities included door-to-door canvassing for signatures, establishing a forum to “explain in detail the Padlock Law” to the public, and sending an official letter to the federal government “urging immediate disallowance” of the law. Despite the concerns raised by activists across the country, it took another two decades before the Padlock Law was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court of Canada.

The CCA operated until the early 1940s, then, after a hiatus, re-emerged briefly in the 1950s. Many members of the CCA would go on to participate in the creation of new activist groups in the city of Windsor.

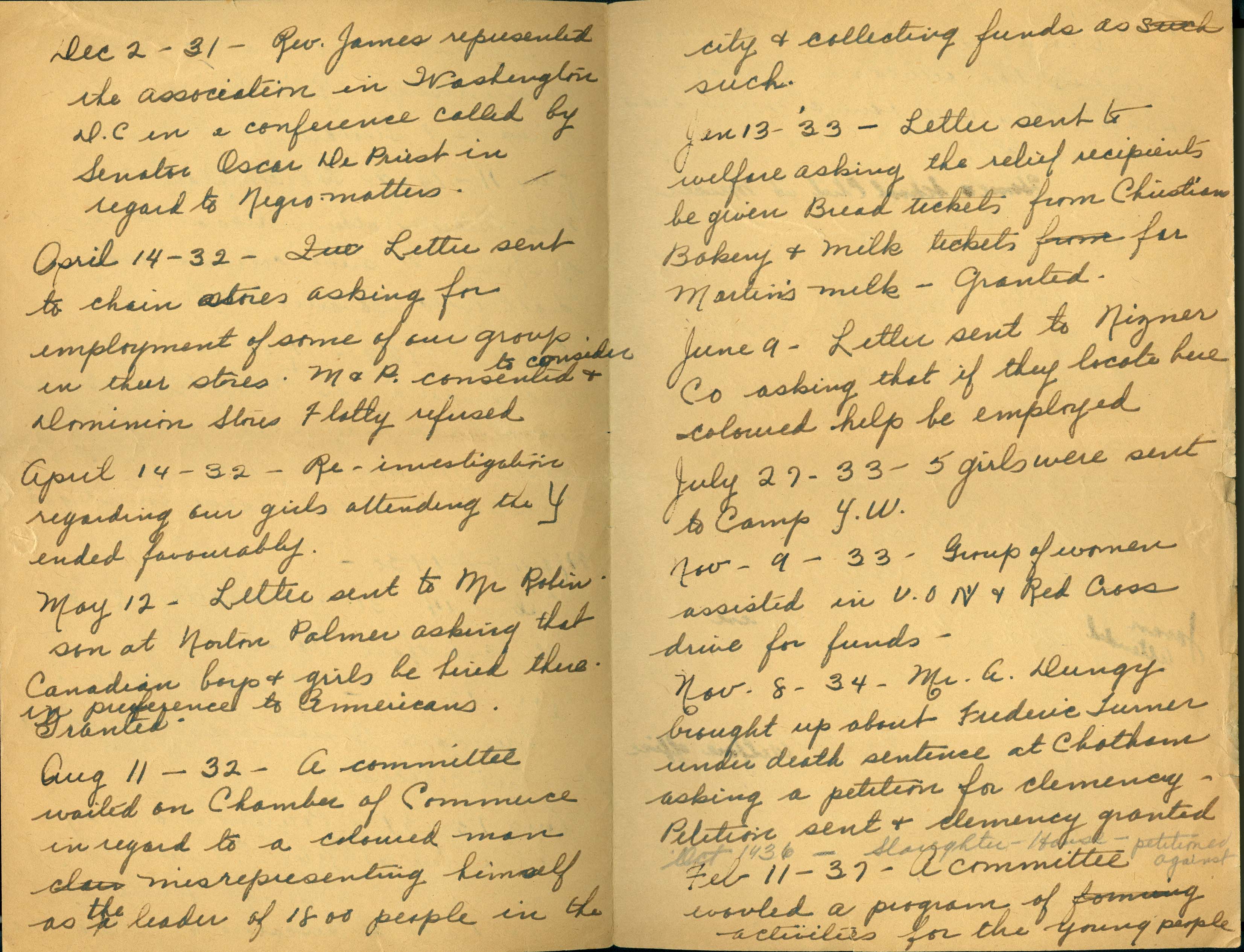

The Windsor Interracial Council

Continuing the work of the Central Citizens' Association was the Windsor Interracial Council (WIC), later renamed the Windsor Council on Group Relations. Founded in 1947 and operational for approximately a decade, the Council was composed initially of seventy-five Windsorites from a variety of ethnic and religious backgrounds, who were interested in making the city more inclusive and accommodating. Membership came from Black residents like Mahlon C. Dennis, Reverend L.O. Jenkins, Dr. Roy Perry, Dorothy Nolan, Lyle Talbot, Charles Brooks, Nancy Watkins, and Reverend Arthur Jelks as well as from other community groups including the Jewish Community Council, the Federation of Russian Canadians, Y.M.C.A., Men Teachers Federation, Women Teachers Association, and members of the United Auto Workers.

The WIC established numerous committees on cases of discrimination and specific issues encountered by various minority groups. Led by Lyle Talbot, the WIC produced an audit report titled, “How Does Our Town Add Up: A Community Audit Report” in 1949 and a follow-up in 1957. The audit observed the presence of discrimination in various sectors of the city: employment, housing, accommodations, public facilities, recreation, education, and public health. Through a series of interviews with residents and questionnaires for employers, health care providers, real estate brokers and industry leaders, the report highlighted the presence of discrimination in each category. Housing and employment discrimination were identified as the highest and most pressing issues affecting Black Windsorites.

The questionnaire found that employers generally did not consider hiring “persons of certain racial minority groups except as porters, janitors… and other menial types of work.” Many employers suggested hiring Black workers would result in a loss of customers or pushback from their current employees. Moreover, factories generally denied office positions for non-white employees, and most stores refused to hire persons of certain racial minority groups. The findings of the WIC report corroborate many of the concerns voiced earlier by the CCA.

The WIC utilised the findings of the report to call for an amendment to the Land Titles Act to contest restrictive covenants and the creation of a “fair employment practices act” by parliament. By 1950, the provincial government amended the Conveyance and Law of Property Act to end the legal use of covenants that restricted individuals from purchasing property based on “race, creed, colour, nationality, ancestry or place of origin.” A year later, the province of Ontario would pass the Fair Employment Practices Act of 1951. Even with the passing of these more inclusive laws, landlords, landowners, and employers continued to discriminate against people of colour in various ways. As we will see, an organisation was needed for residents to report cases of racial discrimination in accessing the most fundamental of rights.

Working outside of the city, the WIC was among the first to endorse Windsor resident Hugh Burnett in his legal case against a restaurant in Dresden, Ontario following his being denied service on the grounds of racial discrimination. The WIC also held meetings with other organisations like Toronto’s Association for Civil Liberties to discuss issues of racial discrimination across the province.

The Guardian Club

The Guardian Club continued the work of the CCA and WIC by tackling systemic issues of discrimination against Black Canadians, partnering with the Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC). The Guardian Club facilitated a nation-wide Black coalition, organising regional civil rights groups under the National Black Coalition of Canada. Together, the Coalition advocated for housing equality, fair employment practices, and the desegregation of every facet of Canadian society.

The club’s involvement with the OHRC began in the early 1960s, following an incident involving Dr. Howard McCurdy and his brother-in-law at Windsor’s Roseland Golf Course. When Howard and Nelson were barred from entering the golf course in South Windsor on account of the club’s policy of “no Americans,'' McCurdy reached out to OHRC director Dr. Daniel Hill who, along with lawyers Alan Borovoy and Saul Nosanchuk, came to Windsor to settle the dispute. Upon finding sufficient evidence that the golf club had racially discriminated against McCurdy and his brother-in-law under the Ontario Human Rights Code, Dr. Hill requested more research on how widespread the issue of racial discrimination was in Windsor. From here, members joined to aid in conducting interviews and test cases to assess levels of discrimination in accessing fair housing, employment, and public services.

The Guardian Club’s membership included many activists of the Corridor such as Howard McCurdy ( Professor of Biology at the University of Windsor and later became a Member of the House of Commons), Patricia McCurdy (Interior Designer and Artist), Dr. Philip Alexander (Professor of Electrical Engineering at the University of Windsor), J. Lyle Browning (businessman and the first Black Canadian to be appointed president of a major auto-parts manufacturer), Eugene Steele (Windsor’s first Black firefighter), Frieda Parker Steele (nurse and local activist), Reverend L. O. Jenkins, Justin Jackson (President of the Windsor West Indian Association), along with the Watkins, White, Green, Dungy, Olbey, Dennis, and Walls families, who had contacts with the larger community.

Activists from Toronto included Dr. Wilson Head (sociologist and director of Research and Planning for the Social Planning Council of Toronto), Dr. Daniel Hill (sociologist and later the chair of the OHRC), as well as Alan Borovoy (lawyer and the director of the Ontario Labour Committee for Human Rights).

The OHRC established testing procedures for members of the Guardian Club as they conducted test cases in the city. As detailed by several interviewees, Black members would inquire about jobs or rental listings after which they would be turned away with answers such as “we are no longer hiring” or “this is no longer available.” However, when white members inquired about the same position or apartment soon after, it was suddenly available. These test cases provided the newly established OHRC with clear evidence of racial discrimination against Black Canadians.

One of the major reports produced utilising data collected by the Guardian Club was The Position of Negroes, Chinese, and Italians in the Social Structure of Windsor, Ontario, which was produced by Dr. Rudolf A. Helling at the University of Windsor for the OHRC in 1965. The report detailed some of the revelations of the Guardian Club’s test cases, observing the levels of discrimination and the systemic barriers in place and how they affected the quality of life for Black Canadians in the city. The report argued that Windsor’s Black population “had experienced the greatest difficulties… in restaurants, taverns, with law enforcement officers, educational officers, employers, fellow workers and previous employers.” Data collected from the 1949 and 1957 community audits was also used in Helling’s report.

Helling considered the Guardian Club to be at “the forefront of the integrationist movement” observing existing legislation and utilising it to address and prevent discrimination, as well as instituting educational initiatives to break down barriers and limit prejudice. Not everyone agreed, however. Some members of the community found the tactics of the Guardian Club to be too radical, and the findings of Helling’s report were challenged by those who believed it downplayed the successes of individuals in the community.

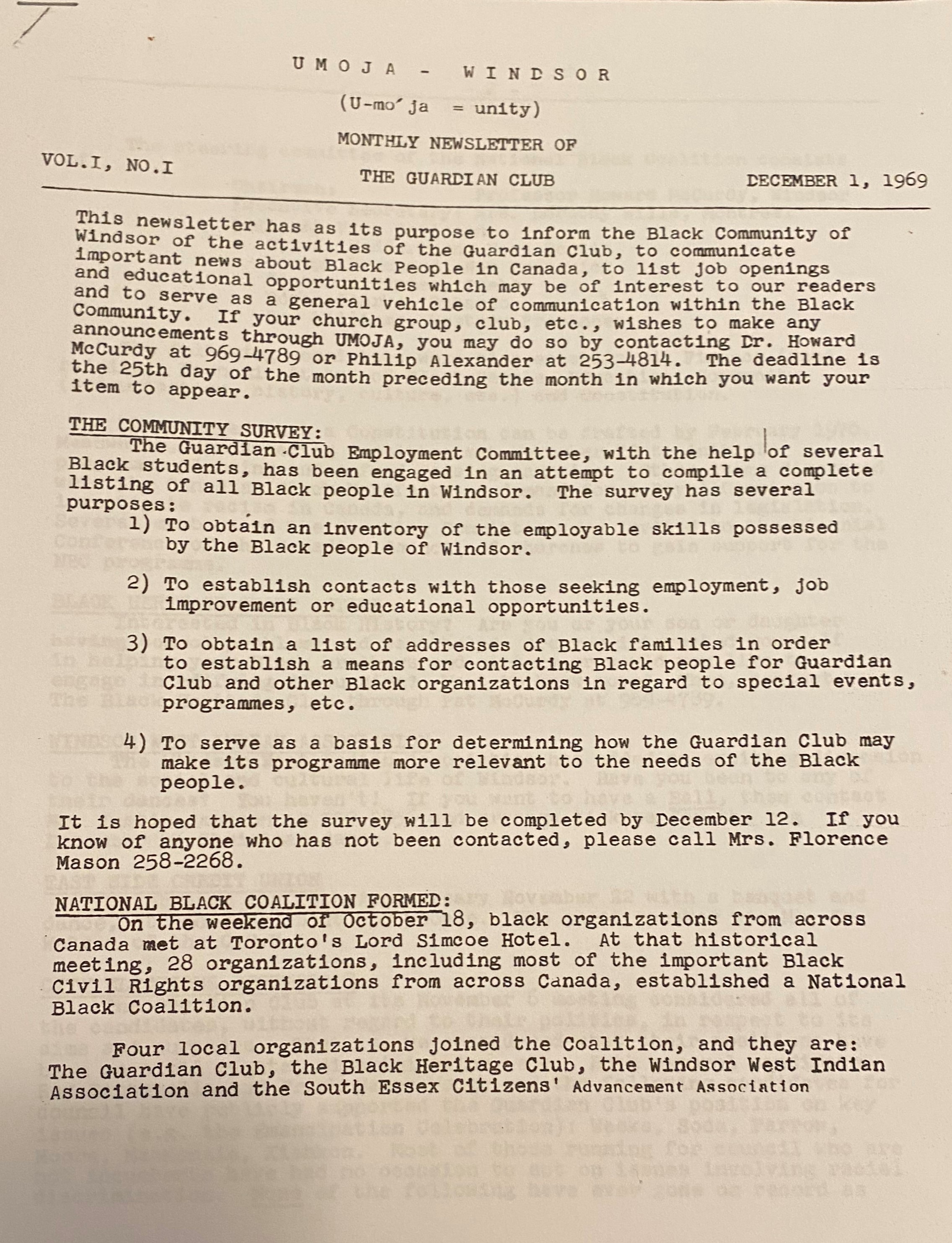

Aside from their work with the OHRC, the Guardian Club continued many of the initiatives started by local civil rights organisations in Windsor. A regional office was established in Windsor to ensure residents had access to resources; an employment committee was formed to observe and report on the status of Black employment in the city; a monthly newsletter UNITY was created to keep members and residents informed on local politics and club programs; and additional resources were provided by local organisations like the West Indian Association and the East Side Credit Union (formerly Coloured Credit Union) which provided financial and budgeting assistance to the community. A full issue of the UNITY newsletter is available by clicking here.

Like the CCA, the Guardian Club attempted to push the boundaries of racial discrimination and social acceptability by finding job opportunities for which local Black residents could apply. One example of a successful placement was that of Gale Carter. Through the efforts of Howard McCurdy, an interview was secured for Gale, and she became the first Black typist hired by Hiram Walker in 1965. She remained a well-respected member of the Hiram Walker team for more than thirty years.

The Guardian Club engaged the public with their “From Slavery to Freedom” exhibit at the University of Windsor, which sought to teach the public about Black Canadian history in Southwestern Ontario. The first of its kind to be held in Windsor, the 1965 exhibit showcased various archived pieces including the family heirlooms of freedom seekers, farming implements, and monographs.

In 1969, the Guardian Club along with Black organisations across Canada came together to form the National Black Coalition of Canada (NBCC) following the occupation at Sir George William University (Concordia University) in Montreal. Under the leadership of Dr. Howard McCurdy, the NBCC was the first national civil rights organisation formed in Canada to address systemic issues of racial discrimination. However, internal disagreements saw the Windsor chapter separate from the national body by the 1980s. Some members came together under a new organisation, the Windsor Human Rights Association, and later the Windsor and District Black Coalition.

The legacy of these three Windsor-based civil rights organisations and their many offshoots can be seen in the passing of human rights legislation in the Province of Ontario, and certainly nationwide. The Black community worked tirelessly to document the various forms of discrimination they and others experienced in the hopes of enacting genuine change and allowing visible minorities to live, work, travel, and shop as equal citizens.