Pillars of Society: Religious Institutions

By Willow Key

More than a religious institution, the Black church has long been the epicentre of Black life in Canada. A stabilising force, the Black church historically served as a place of refuge and community, inspiring a myriad of social organisations, educational institutions, businesses, and social outreach programs geared toward the advancement of those of African descent. In Windsor, the African Methodist Episcopal, British Methodist Episcopal, First Baptist, and Pentecostal God in Christ Churches have sustained the community of the McDougall Street Corridor for nearly two centuries.

In a city where Blackness was often viewed as an impediment by the larger society, churches within the McDougall Street Corridor offered residents a sense of belonging, serving as a form of social armour against discrimination and prejudice. These churches allowed Black Windsorites to embrace their authentic selves, to invent and create a spiritual world that would sustain and fulfil them in ways often unattainable outside the sanctuary that was the church.

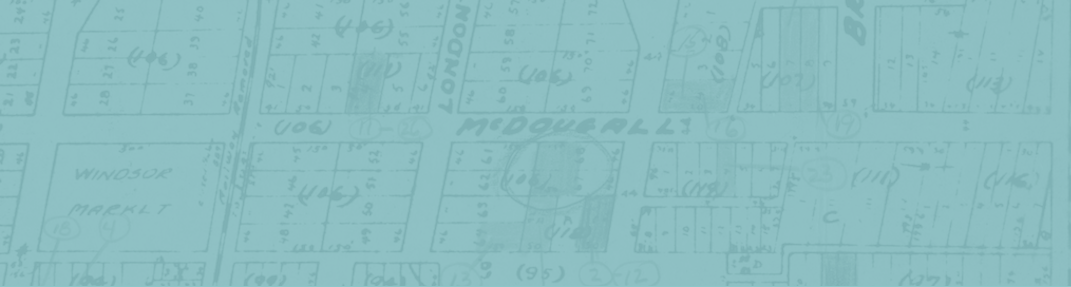

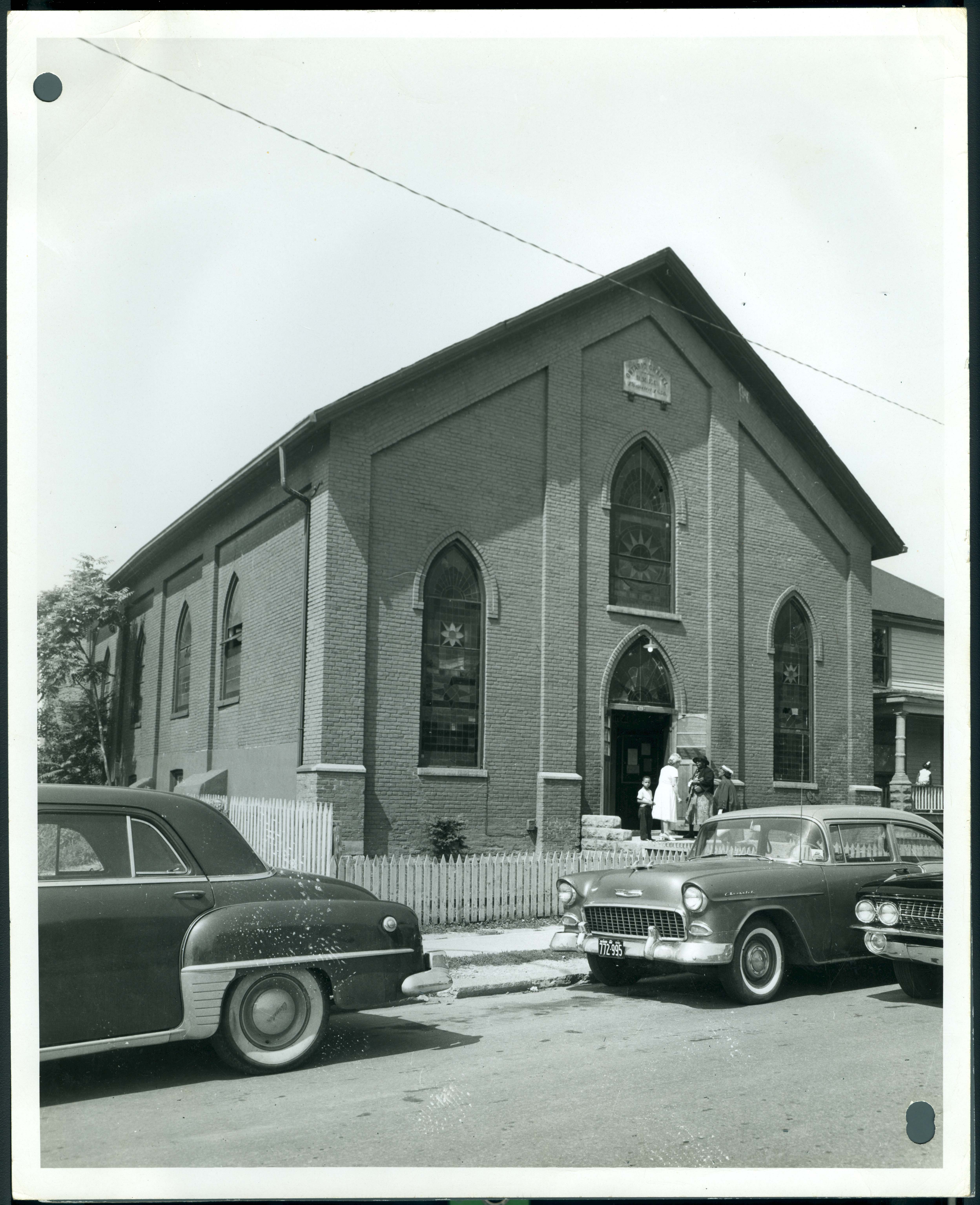

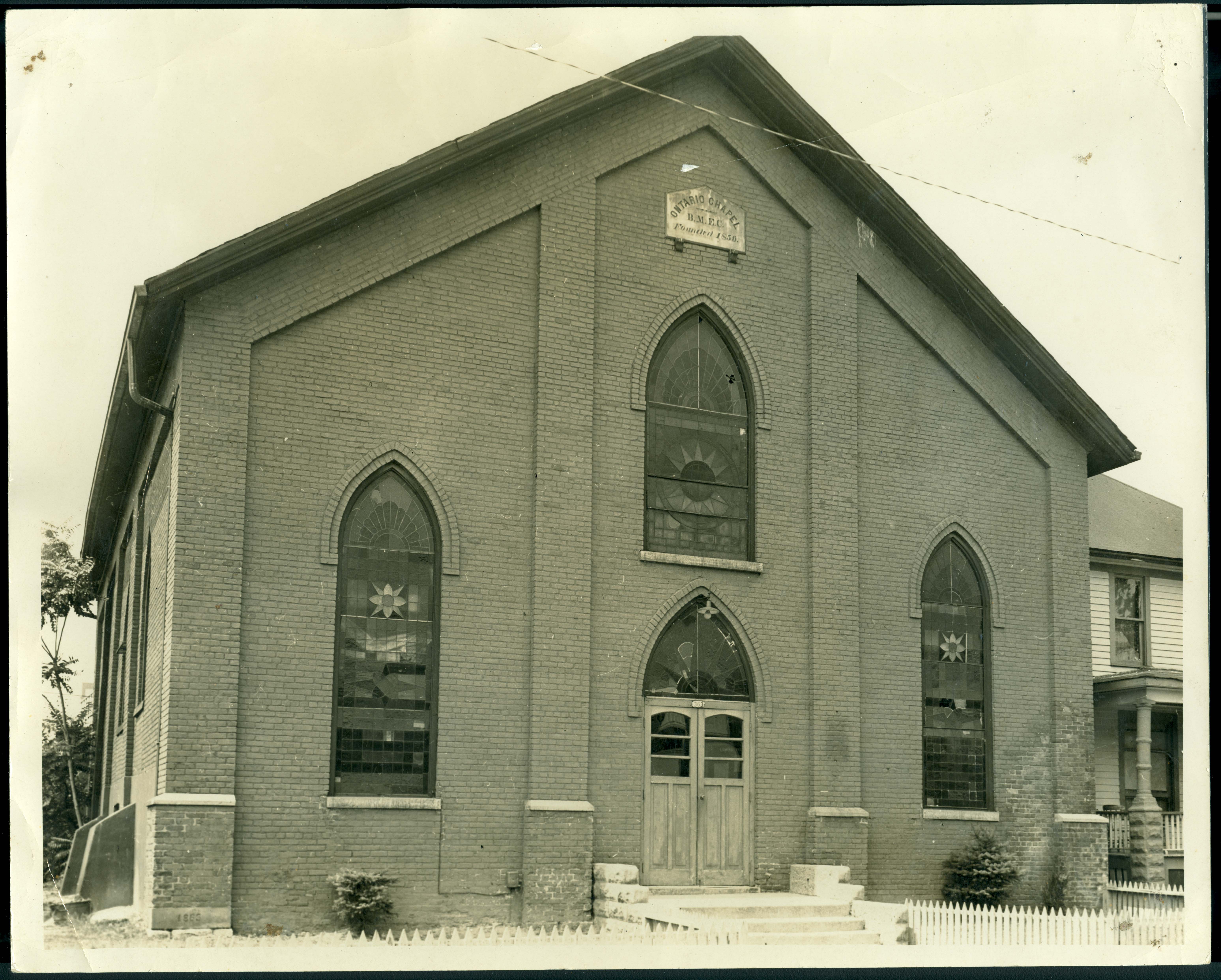

British Methodist Episcopal Church

The first of the five main churches to be built within the boundaries of the Corridor was Windsor’s British Methodist Episcopal Church (BME) on McDougall Street near University Avenue. Emerging from the African Methodist Episcopal Church in 1856, the BME church is a uniquely Canadian denomination of Black worship. With the influx of those seeking refugee from the United States, the AME Church in Canada grew rapidly. By the 1850s, however, Canadian AME members increasingly feared the dangers of crossing the border for church conferences and desired autonomy from the American body as a result.

Windsor’s congregation was established in 1852 by newly emancipated slaves, with the original wooden church being built two years later. By 1863, the congregation of freedom seekers had laid the cornerstone of their new brick church at 363 McDougall Street. With water from the Detroit River used for the mixing of the mortar, the church would eventually be dedicated in 1868.

A pillar of the community, the BME church has had a long history of social action, providing residents of the McDougall Street Corridor with religious guidance and much needed services. With dedicated leaders like Reverend William Harrison, Rev. F. O. Stewart, and Rev. I. H. Edwards, the church was instrumental in facilitating numerous community organisations aimed at addressing the needs of Black residents. In 1929, the church participated in the formation of the Coloured Citizens’ Association (later Central Citizens’ Association), a local civil rights organisation that would serve as the forerunner to Windsor’s Guardian Club and Black Coalition.

In 1934, the Hour-a-Day Study Club emerged from within the church to address the needs of local Black students, providing educational aids and grants that encouraged Black youth to reach their highest academic potential.

At the outset of World War II, women of the church established the War Mothers’ Protective League, ensuring young men of the Corridor would receive care packages with goods, letters, and much needed supplies while overseas. Some of the thank you letters the War Mothers’ Protective League received can be read by clicking here.

The church’s presence within the community was deeply impacted by Windsor’s postwar urban renewal program, which resulted in the expropriation and demolition of the 107-year-old church in 1961. Initial estimates for restitution of the property were fifty thousand dollars. Understanding that the cost of purchasing new land and rebuilding their church would be an expensive endeavour, the BME church pushed back, hiring several lawyers to negotiate a fair price for the historic building in arbitration. As reported in the church’s Building Fund Committee,

Then the blow came. In May, 1961 we were informed that the city was expropriating our property. We were given until Sept. 15, 1961 to vacate. Needless to say it was not a time for weeping and gnashing of teeth. It was a time for action.

The Church approached James E. Watson, the first Black city solicitor and resident of the Corridor, to aid them in the expropriation process. However, his affiliations with the BME Church disqualified him from managing the case; he recommended his assistant, Joseph Ferris. Following months of preparation for a lengthy arbitration and a few days in court, the congregation received much less in restitution than they had hoped for,

we felt that we should accept this settlement. We had already lost two thousand dollars. Before we lost more we thought we should settle… The arbitration was very costly… Our legal fees were higher… The amount realised from our arbitration meant that we would have to adjust our expenditures.

In the end, the congregation had no choice but to raise almost twenty thousand dollars in additional funds for the construction of their new church on University Avenue. Donations and loans from members, church organisations, and sympathetic contractors made the building of their new church possible. While the new church was under construction, the BME congregation was invited to continue Sunday services in the hall of the Northstar Masonic Lodge No. 7 which was located at 1029 McDougall Street.

The BME Church had been informed that their original property would be utilised for the much-needed expansion of the civic square, however it remained a parking lot for decades until it became the location of the city’s Service Canada Centre.

First Baptist Church

Founded in 1853 by Reverend William Troy, Windsor’s First Baptist Church is the second oldest church within the McDougall Street Corridor. Before the establishment of a physical church, the congregation would routinely gather in homes around the neighbourhood for small prayer meetings. Utilising funds Reverend Troy had collected on a grant-seeking mission to England, his congregation of freedom seekers built their church by hand, crafting bricks with water carried from the Detroit River. In 1858, the cornerstone of First Baptist was laid on McDougall Street, near University Avenue. By 1915, the congregation had grown substantially, and a new church was raised at 710 Mercer Street.

The church was home to several pastors including R. L. Bradby, C. L. Wells, H. L. Talbot, H. L. McNeil, A. R. James, and A. Randall. In 1945, First Baptist found stability and longevity in Reverend Mack Brown, who remained pastor until his passing in 1985, serving his church for forty years.

Under the leadership of Rev. Mack Brown, the First Baptist Church established and continued numerous clubs including the Helping Hand Society, the Boy’s Club, Young Women’s Missionary Circle, Canadian Girls in Training, and the Explorer Group. The church also supported local social organisations including the Fellowship of Coloured Churches Credit Union, the Central Citizens’ Association, the Hour-a-Day Study Club, and the Windsor Art and Literary Club.

Reverend Brown and his congregation worked tirelessly to address the needs of members of the church as well as other residents of the McDougall Street Corridor, especially during the decades of civil rights activism. Like many Black churches across North America, Windsor’s Black churches had long served as beacons of hope in the face of racial discrimination. As Elwood Kersey commented in 2006,

There were a lot of places where we couldn’t go and a lot of things we couldn’t do so they brought those things to us. There were functions in other areas that took place where you weren’t a part of, but they brought it back to us.

In 1990, Bishop Arthur T. Harrison recalled,

At times there were certain places we couldn’t go in. At the theatres we had to sit in the balcony… the prejudice toward black Canadians has changed slowly… you still have a lot of it here yet.

In response to these segregationist practices, First Baptist hosted luncheons, teas, and dinners within the church, providing alternative accommodations for social services made inaccessible to Windsor’s Black population. Member Ella “The Boss” White was famous for feeding hundreds with her signature chicken dinners. As Reverend Mack Brown summarized,

We couldn’t go to your restaurants so we had to go to our Silver teas.

Reverend Mack Brown used his position as moderator of the Amherstburg Regular Missionary Baptist Association to support the work of local civil rights activists and legislation within the province. In 1968, the Association held a meeting on the topic of racial discrimination, led by Michael J. Marentette, of Windsor’s branch of the Ontario Human Rights Commission. The issue of the Windsor Police Department and their decision to block the community’s annual Emancipation Day Celebrations in response to the 1967 Detroit Uprising was of particular interest to Reverend Brown and his community.

Tanner African Methodist Episcopal Church

As Methodist churches in the late eighteenth century declared their opposition to slavery, free African Americans across the northern United States began joining racially mixed congregations. However, an anti-slavery stance did not necessarily mean that Black people were seen as socially or intellectually equal. When Black Methodists were faced with racially restrictive practices at Philadelphia’s St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church, a self-emancipated man, Richard Allen, chose to establish his own church. In 1794, the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) was established in Philadelphia as an independent Black Christian denomination. The AME denomination was recognized in 1816.

The AME denomination spread throughout Canada as freedom seekers and abolitionists brought their religious beliefs with them across the border. The American AME Church was instrumental in establishing Underground Railroad stations, providing networks of refuge and aid across the northern states and into Canada. By the early 1830s, numerous AME churches dotted the landscape of Southwestern Ontario.

Windsor’s AME congregation emerged in 1852, following the construction of a small frame church on McDougall Street. The AME Church in Canada experienced a separation from the American body in 1856, which resulted in the creation of the British Methodist Episcopal Church. In the aftermath of the Civil War, those who had opposed the separation sought to return to the AME tradition. In 1888, Bishop Benjamin E. Tanner purchased an existing church that had been built for the Mercer Street Baptists and this location at 408 Mercer became the home of Windsor’s Tanner AME Church.

Official service was held in 1890, with an estimated twenty-five charter families associated with the church. In step with the other staple churches within the Corridor, Tanner AME served generations of residents with spiritual guidance and social justice. Home to the Women’s Missionary Society, Tanner Young People’s Choir, and many members of the Order of the Eastern Star (Victoria Chapter No. 3), the church also organised luncheons, pancake suppers, family services, and events for children.

The church routinely supported residents within the Corridor with the issues that they faced. Under the leadership of Reverend G. A. Coates and L. O. Jenkins in the 1950s and 1960s, Windsor’s AME congregation organised Black history lectures and hosted guest speakers from across Canada and the United States to discuss civil rights and religious issues. Church leaders like Reverend G. A. Coates and L. O. Jenkins participated in a variety of panels and hearings regarding racial discrimination within the city. In the 1960s, Coates and Jenkins participated in the “Fellowship in the Gospel” program, which established racially mixed and inter-denominational services to break down barriers in churches across the city.

After eighty-five years, Tanner AME Church was expropriated by the City of Windsor and demolished in 1962. With fifty families belonging to the church, a week-long celebration was organised commemorating the history and legacy of Tanner AME and the AME denomination in Windsor. Leaders from other churches were present; Bishop C. L. Morton and Reverend Mack Brown encouraged their members and choirs to participate in the final service and dinner.

One of the last events held at the church was a sing-song party for the congregation's one hundred and fifty children. The Windsor Star described how,

This was the last program for the children, and it had been designed to fill their afternoons, and to leave them with a remembrance of Tanner AME Church.

As was the case for the BME church, the AME congregation had no choice but to establish a fundraising drive for the building of their new church due to minimal restitution. During this period of construction, the Tanner AME congregation conducted their services in the hall of the North American Masonic Lodge No. 11 located at 900 Mercer Street. The new church was completed in 1963 and is located at 733 McDougall Street. The site of the former church property is now at the centre of a public housing complex.

Mount Zion Church of God in Christ

In the late nineteenth century, a new form of religious fervour emerged from the southeast and Delta regions of the United States. Referred to as the “holiness movement,” Black Christians began popularising expressive forms of worship, which eventually led to the creation of a new denomination, Pentecostalism. In 1897, Tennessee pastor Charles Harrison Mason established what would become the most popular Pentecostal denomination, the Church of God in Christ (COGIC). This southern religion was brought to the Detroit border region in the early twentieth century and was expanded by the renowned Bishop C. L. Morton Sr., the founder of the Canadian and International Churches of God in Christ. Establishing churches on both sides of the border, Morton was instrumental in erecting five Pentecostal churches in Southwestern Ontario and six in the United States.

Bishop Morton began preaching in Windsor in the early 1920s, holding services initially in a small rented hall on Tuscarora Street near Glengarry Avenue. He formally established the Church of God in Christ in 1926 and the church was incorporated in 1935. Later, the church was moved to the second floor of a McDougall Street machine shop referred to as the “little secluded church near the banks of the busy Detroit River.” Eventually membership grew and through fund-raising efforts by the congregation, they were able build their own church at 795 McDougall Street in 1939.

Mount Zion Church of God in Christ gained international notoriety for its annual river baptisms, bringing thousands of spectators to Windsor, most notably in the 1940s and 1950s. As the Windsor Star detailed,

People came from all over the states. People would line the banks of the river to see it.

Chartered buses travelling from as far south as Indiana brought Black churchgoers to Windsor to witness this holy event. At the foot of Campbell Avenue, the service began with Bishop Morton baptising participants, fully immersing them in the waters of the Detroit River to symbolise the washing away of the old and the beginning of a new life. In the afternoon, a service was held at the church with a barbeque and festivities in the evening.

A contributing factor to the expansion of Pentecostalism out of the south was the popularity of gospel music. Inspired by African American spirituals and folk songs, gospel adapted and popularised these sounds in the 1920s through religious “race-records.” These were wax recordings of sermons and church choirs incorporating ancestral sounds with the good word. Churches like Mount Zion celebrated their faith with song and musical prayer.

Beginning in 1935, Bishop Morton Sr. began broadcasting a religious radio show on Chatham’s local station. Windsor’s CKLW later acquired Bishop Morton and his Radio Chorus, airing weekly Sunday broadcasts from 1936 until his passing in 1962. Bishop Morton’s eldest son, C.L. Morton Jr., continued his father’s ministry and radio show well into the 1970s when it was acquired by Detroit’s WGPR.

The popularity of Bishop Morton’s captivating sermons and weekly radio ministry garnered the church hundreds of local members. These sermons also attracted thousands of frequent listeners across both sides of the border, introducing generations of Canadians and northern Americans to the sounds of gospel music and Black southern religious traditions.

The sounds of the Radio Chorus, Evangelist Quartette, and the Flying Cloud Quartette frequently rang out into the streets of the McDougall Street Corridor, drawing residents out of their homes and onto their porches.

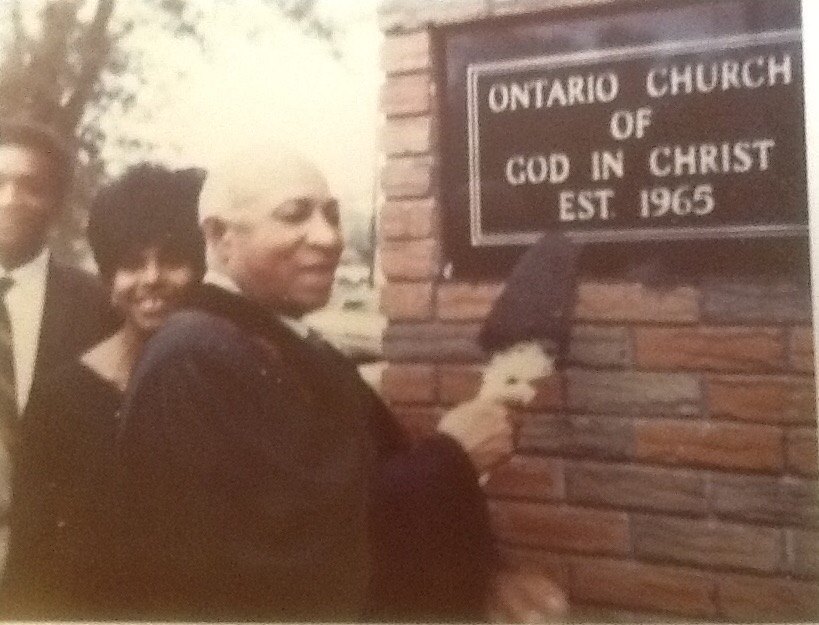

Harrison Memorial

Arthur T. Harrison, a student of Bishop C. L. Morton Sr., left the Church of God in Christ following Morton’s passing and established Harrison Memorial, originally known as the United Church of the First Born. Born to a religious family (the nephew of Reverend William Harrison and famed The Green Pastures Broadway actor Richard Harrison), Arthur was determined to establish his own congregation, initially holding church services in his home beginning in 1963. He would later rent a room in the North American Masonic Lodge No. 11 on Mercer Street, where his church would remain until 1967.

When church membership exceeded one hundred members, Bishop Harrison set out to establish a more permanent home for his congregation. As he recalled,

I just wanted a place where we could come in and not have anyone tell us to move. I prayed to the Lord… I just wanted a simple building where we could praise the Lord and I’d be happy.

With generous donations from worshippers and the community, over the next year Bishop Harrison’s congregation built their church by hand. Every weekend, dozens of men and women from Windsor and Detroit donated their time and their diverse skills to the project, adding their own personal touches with every brick laid and every brush stroke,

Of course we worked together. I could call to Detroit. They would come over sometimes eight or nine car loads at a time…. We got money from them and what we could raise ourselves.

When construction was completed in the fall of 1968, Bishop Harrison led all 150 members of his congregation on a march from the Masonic Lodge to their new home at the corner of Mercer and Cataraqui Streets:

We all marched down the street singing praise. I say we built the church by faith.

Like Mount Zion, Harrison Memorial incorporated spirituals and gospel music into worship, establishing the Unique Ontario Chorale, a choir that captivated audiences in Montreal at Expo 67. The thirty-vocalist choir led by director Naomi Banks also performed in Washington D. C., for the International Youth Congress of the COGIC, San Antonio for HemisFair, and Detroit’s Masonic Auditorium.

Like other religious leaders in the community, Arthur Harrison had to navigate a period of heightened racial tensions, to which he responded firmly and swiftly. In 1968, following the Detroit Uprising, the Windsor Police Commission denied a permit to organisers of the annual Emancipation Day carnival. In response, civil rights activists and Ontario Human Rights officials, Dr. Howard McCurdy, Alan Borovoy, Dennis McDermott, Senator Coleman Young, and Michael Sumner were joined by Bishop Harrison at a sponsored event to discuss the prejudice aimed at the annual celebration and the discrimination Black Windsorites were experiencing.

The Black church in North America was born from a struggle for equality and leaders like Bishop Harrison recognized the important role the church played in advocating for the needs of its people.

In 1965, Rudolf A. Helling, Professor of Sociology and Anthropology at the University of Windsor, published a report titled, “The Position of Negroes, Chinese and Italians in the Social Structure of Windsor, Ontario.” In it, Helling included scathing commentary on the position of the city’s Black religious leaders and their limited efforts to integrate their congregations:

Negro ministers are primarily of the appeasement type of leadership… [they] would find it difficult to have a similar position in an integrated society. Appeasement type leadership favours the status quo combined with easement of individual problems rather than community problems.

While his report unearthed important information on the discrimination faced by racial minorities in the city of Windsor, he failed to recognize the quiet, yet powerful role Black churches served within the community. In Windsor, and across North America, Black life has long centred around the church. Helling misinterpreted the role of the church within Black society; it was never simply a religious institution, but a political, economic, and social one as well. These churches worked alongside one another in providing services to their communities that were often denied to them. During the formation of the Central Citizens’ Association, a civil rights group initiated by religious leaders in the 1920s, meeting minutes detail that,

It was the consensus of opinion that there was always a certain amount of danger it be faced when ministers take the lead in organizations of the kind desired, but under the circumstances it was imperative for the ministers to take the initiative in the hope that our laymen will eventually realize the importance of giving time and attention to community affairs.

The goal of the Black church has always been to support educational and social programs, facilitate community organising and outreach, and provide religious and spiritual guidance tailored to the needs of the community. In this effort, Windsor’s Black religious leaders were present and courageous.