Black Social Clubs and Organizations

By Willow Key

While churches addressed the spiritual and everyday needs of the community, there were other institutions that provided residents of Windsor’s Black community with camaraderie and empowerment. Reviewing the works of intellectuals like W.E.B. Du Bois and Paul Gilroy can shed light on the existence and purpose of Black social organisations. People of the African diaspora have often operated within a state of double consciousness, establishing agency within separate, often invisible institutions, away from the prying eyes of the dominant society they exist within.

In Windsor, Black social organisations were typically created in response to community members being denied access to white spaces. Serving a unique world behind the veil of segregation and racial discrimination, Black fraternal and social organisations afforded those of African descent an outlet of authenticity, camaraderie, and refuge from an often-unfair world.

Many residents of the Corridor were socially active throughout their lives, often having membership in multiple clubs and organisations. In the same way that much of Black social life involved the churches, social clubs fulfilled other community needs.

The first of these Black institutions to emerge within the Corridor were fraternal organisations and their female auxiliaries, followed by twentieth century benevolent and women’s associations like the Windsor Art and Literary Club, the Hour-a-Day Study Club, the Pivots’ International Club, and the Armstead Athletic Club.

Fraternal Organisations

The oldest fraternal organisation founded by African Americans in North America is Prince Hall Freemasonry. Many members of the Prince Hall Freemasons were involved in the abolitionist movement throughout the nineteenth century. When men like Abraham D. Shadd and Martin Delany emigrated for towns and cities across the province of Ontario, they brought with them the practices and customs of their lodges.

Black Masonic lodges were dedicated to the personal development of their members, striving for truth, justice, equality, and brotherhood. Masons actively promoted education and community as core tenets, fulfilling leadership roles in their community through a pursuit of political activism.

The earliest instance of Prince Hall freemasonry in Canada begins in the early 1850s, around the time of the McDougall Street Corridor’s settlement, with the establishment of three lodges, the Mount Olive Lodge No. 1 in Hamilton (1852), the Victoria Lodge No. 2 in St. Catherines (1853), and the Mount Olive Branch No. 3 in Windsor (1854). The Windsor branch became defunct in 1856, later succeeded by the North American Masonic Lodge No. 11 (originally called the No. 9) in 1868 and the Salem Lodge No. 12 which had been warranted by the Grand Lodge of Michigan in 1871.

By the 1870s, it was clear that Windsor’s Black population was struggling to keep two separate lodges in operation. This issue was resolved by uniting the lodges into the North Star Lodge No. 7 of Windsor. This arrangement would only last for a few decades until North American Masonic Lodge No. 11 was reinstated, and the North Star Lodge No. 7 emerged as a separate lodge in 1902.

Another Black fraternal society in Windsor was the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows. Established in 1886 by George Morgan, the Freeman Lodge No. 2850 operated in a small building on Windsor Avenue, which had been purchased in 1902. This property was later sold to John Landrum in 1928, and the Odd Fellows soon moved their operations to Landrum Hall.

Landrum Hall became the hub of Masonic activity in the Corridor, initially accommodating both chapters of the Prince Hall Freemasons, the Odd Fellows, the Royal Arch, and the Knights Templar. Property records suggest that in 1949, trustees of the North American Masonic Lodge No. 11 purchased a separate property at 900 Mercer Street from the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, which had occupied the plot since 1913. Records also suggest the North Star Masonic Lodge No. 7 rented a suite at what was 311-313 Sandwich Street East in 1913, staying there until the building was repurposed in 1924. By 1931, the lodge was operating from the Masonic Temple located at what was 815 McDougall Street. While the building was owned and operated by local business leader Robert Timms, the trustees of the Lodge later purchased the property in 1961.

As was the case for virtually all Black spaces in the McDougall Street Corridor, both lodges experienced the encroachment of redevelopment by the 1960s. In the late 1970s, the North Star Lodge property was sold and eventually developed for the St. Angela Non-Profit Housing Corporation of Windsor. By this time, the North American Masonic Lodge No. 11 and the North Star Lodge No. 7 had merged again due to dwindling numbers, becoming the American Star Lodge No. 4.

For the Masonic Lodge on Mercer Street, difficulties began in 1978 when the City approved the closure of Niagara Street for the purposes of a 139-unit apartment complex on the north side of Niagara at Mercer. Developers argued for the closure of Niagara to facilitate a buffer between the complex and lodge. This added space allowed for an addition of twenty-six units to the complex, resulting in the total clearance of twenty-two homes.

Both the Lodge and CenterLine (Windsor) Limited pushed back against the City’s plans, arguing that the closure of the street would hinder access and parking for both properties while also jeopardising the value of the land. The Lodge hired a lawyer to present their case, fighting for the right to purchase their portion of the street, at a cost of $9700, to halt any further encroachment. However, in August of 1979, the building was partially damaged by arsonists. To make matters worse, the City ordered both the American Star Lodge and the developer of the apartment complex to split the costs of building a cul-de-sac at the end of Niagara. In addition to their desperate need for funds to rebuild their Lodge, the thirty-four members were expected to cover approximately $30,000 for the road development. The Lodge’s lawyer expressed he had never seen a case in which “the city has closed a street at the request of a developer and then ordered a neighbouring property owner to pay half the costs.”

By the spring of 1980, it was clear that the lodge was unable to cover these costs, with the developers offering to buy the Lodge property at a fair price. The Lodge’s junior warden, Karl Matthews, expressed the despair of the remaining Masons,

We would like to stay at that spot because we’re one of the few Black groups still in that area of the city, which is the centre of the Black population. But we can’t even afford any more legal costs to try to fight this.

With limited options, the Masons had no choice but to give up their property. The land was sold to the city in 1981 for just under $30,000, the estimated cost of American Star Lodge’s share of the road development.

Remaining the longest running fraternal organisation in the city of Windsor, the Prince Hall Freemasons maintained membership for more than a century. However, they too were unable to withstand the physical changes taking place within the McDougall Street Corridor. The Prince Hall Freemasons are still active in a few lodges across Windsor-Essex, with the American Star Lodge No. 4 currently leasing a building in Harrow, Ontario.

Women's Auxiliaries & Social Clubs

Black fraternal organisations had auxiliaries composed of female relatives who participated in female-led orders. For the Prince Hall Freemasons, it was the Order of the Eastern Star and for the Grand United Order of Oddfellows, the Household of Ruth.

Women active in religious institutions typically had few opportunities available for advancement, which made female auxiliaries enticing to women interested in leadership roles. While literature on these female orders is limited, we do know that by the mid-1860s these orders increased in popularity across North America. Windsor’s chapter of the Order of the Eastern Star was known as the Victoria No. 3 (initially 6), and operated in halls and homes throughout the Corridor, including the home of Alderman Isaac Nolan on McDougall Street. The House of Ruth chapter, known as Naomi No. 588, was known to operate in Landrum Hall.

Membership in female auxiliaries provided Black women the experience necessary to establish and command organisations of their own. Female empowerment and leadership were often forged through missionary societies and affiliated religious or fraternal organisations in the early nineteenth century. As was the case for most social organisations that emerged in the McDougall Street Corridor, women were front and centre in their founding and operation.

The Windsor Art and Literary Club

The first of these female-led social organisations to emerge was the Windsor Art and Literary Club (WALC). Established in 1924, this club served as an outlet for women to discuss their interests in the arts, literature, and current events. Organised by Emily Levi and Laura Hyatt, the ladies of the Windsor Art and Literary Club used their organisation’s platform to support local initiatives related to education, social outreach, and civil rights, bringing attention to the various needs of Windsor’s Black community.

Serving as one of the oldest Black social clubs during its time, the WALC raised funds for various causes through annual luncheons, needlework events, musical performances, and festive teas for its members as well as the public. The club routinely invited guest speakers for presentations and reading circles.

Initial meetings were held in the homes of members until club members purchased a home at 1264 Goyeau Street as the permanent location for their operations in 1950. They raised funds for the remodelling of the home through various community events such as Tag Day, a club cookbook, and their popular Bazaars held at Smith’s Auditorium. Unfortunately, the club’s office burned down the same year, and when they attempted to rebuild, they were hindered by zoning laws.

Embodying their motto, “Keep your face always towards the sun and the shadows will fall behind,” the WALC continued its work until the 1960s, contributing to local hospitals, the Red Cross, and other Windsor-based organisations both within and outside of the Corridor.

The Hour-a-Day Study Club

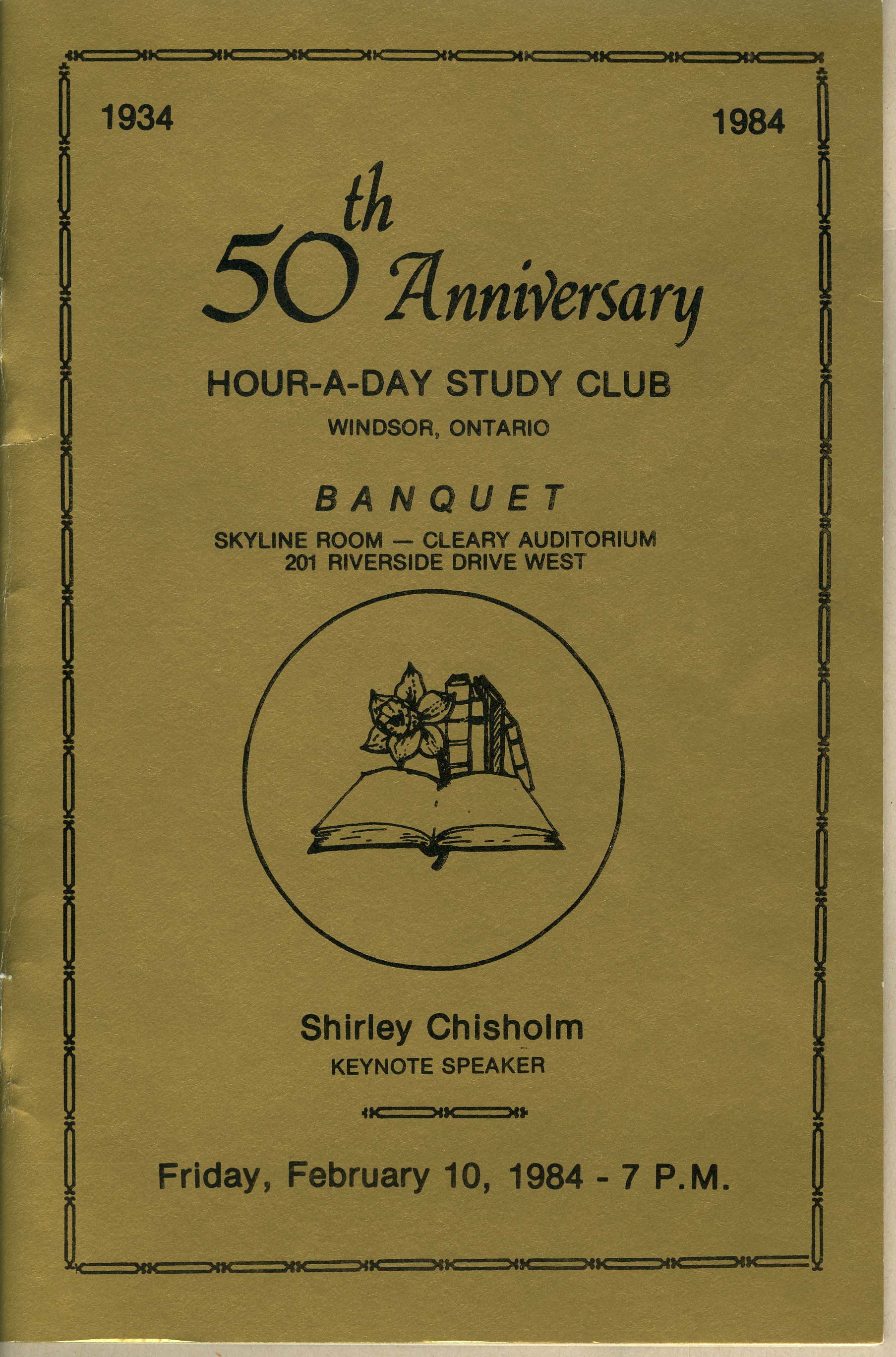

A decade later, in 1934, the Hour-a-Day Study Club (HADSC), was founded by descendants of the Underground Railroad, many of whom belonged to the British Methodist Episcopal Church. Still in existence today, it is the longest running Black women’s non-profit organisation in Canada. The first meeting was held at the home of club president Anna Ardella Jacobs at 1130 Lillian Avenue and subsequent meetings were held in churches within the neighbourhood or at members’ homes. The club was initially known as the Mother’s Club of the McDougall Street Corridor, with club members later changing the name to convey their dedication to spending at least one hour per day reading and focusing on self improvement.

The Hour-a-Day Study Club encouraged education, literacy, and community activism amongst its members and their children. These women advocated for Black academic success by encouraging students to remain in school and strive for post-secondary education. With the combined goal of eliminating the barriers that existed for Black students in post-secondary education, the club later organised an annual scholarship for African Canadian youth in the Windsor-Essex community, a program that still operates today.

Early in its history, the Hour-a-Day Study Club became involved in civil rights initiatives, organising annual high-teas with prominent guest speakers such as Mary McLeod Bethune and Shirley Chisholm. Many members were active in local civil rights groups like the Central Citizens’ Association and the Windsor Interracial Council. Together, members addressed issues of systemic racism and discrimination in housing accessibility, employment, and education.

The War Mothers’ Protective League

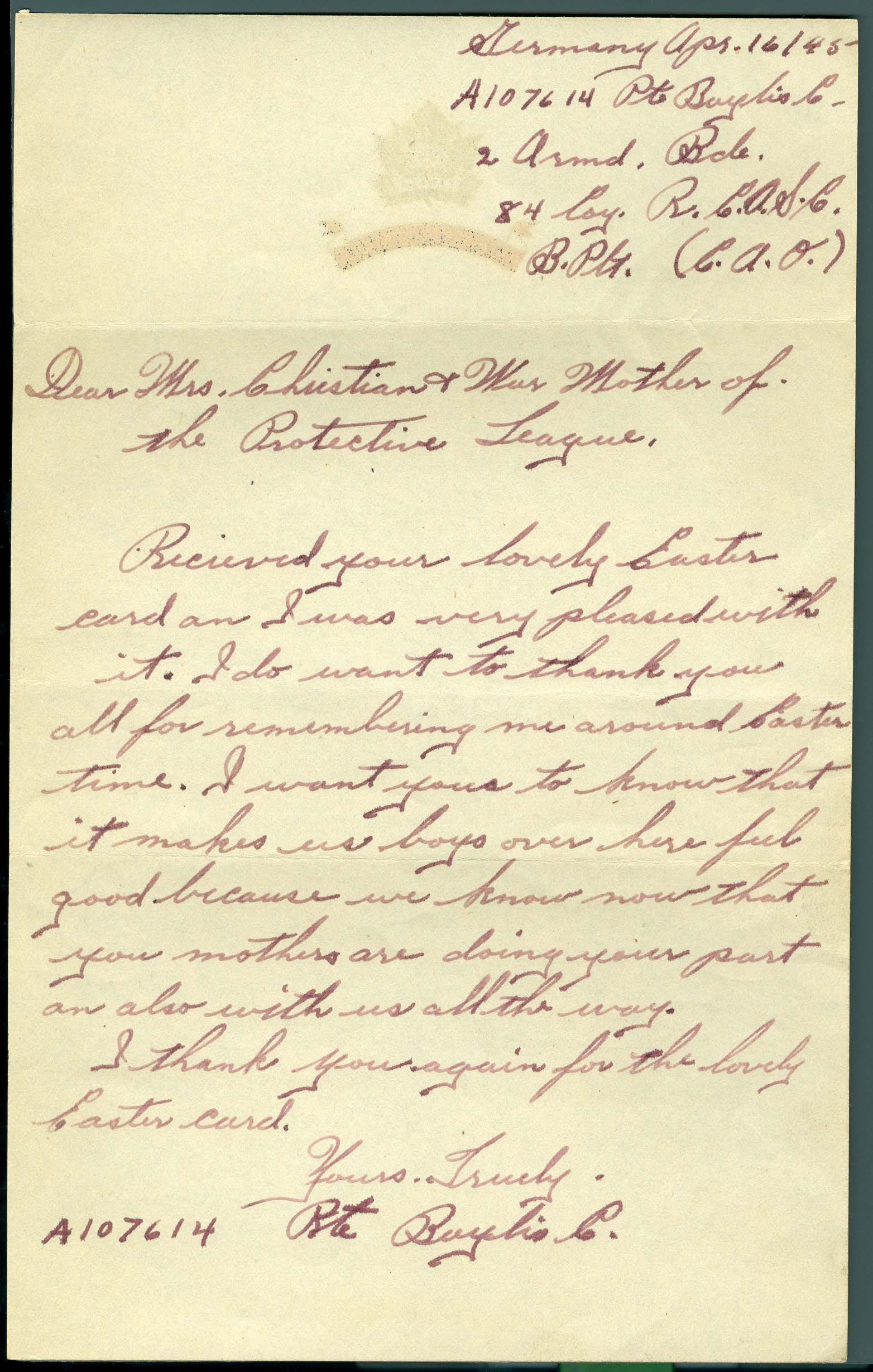

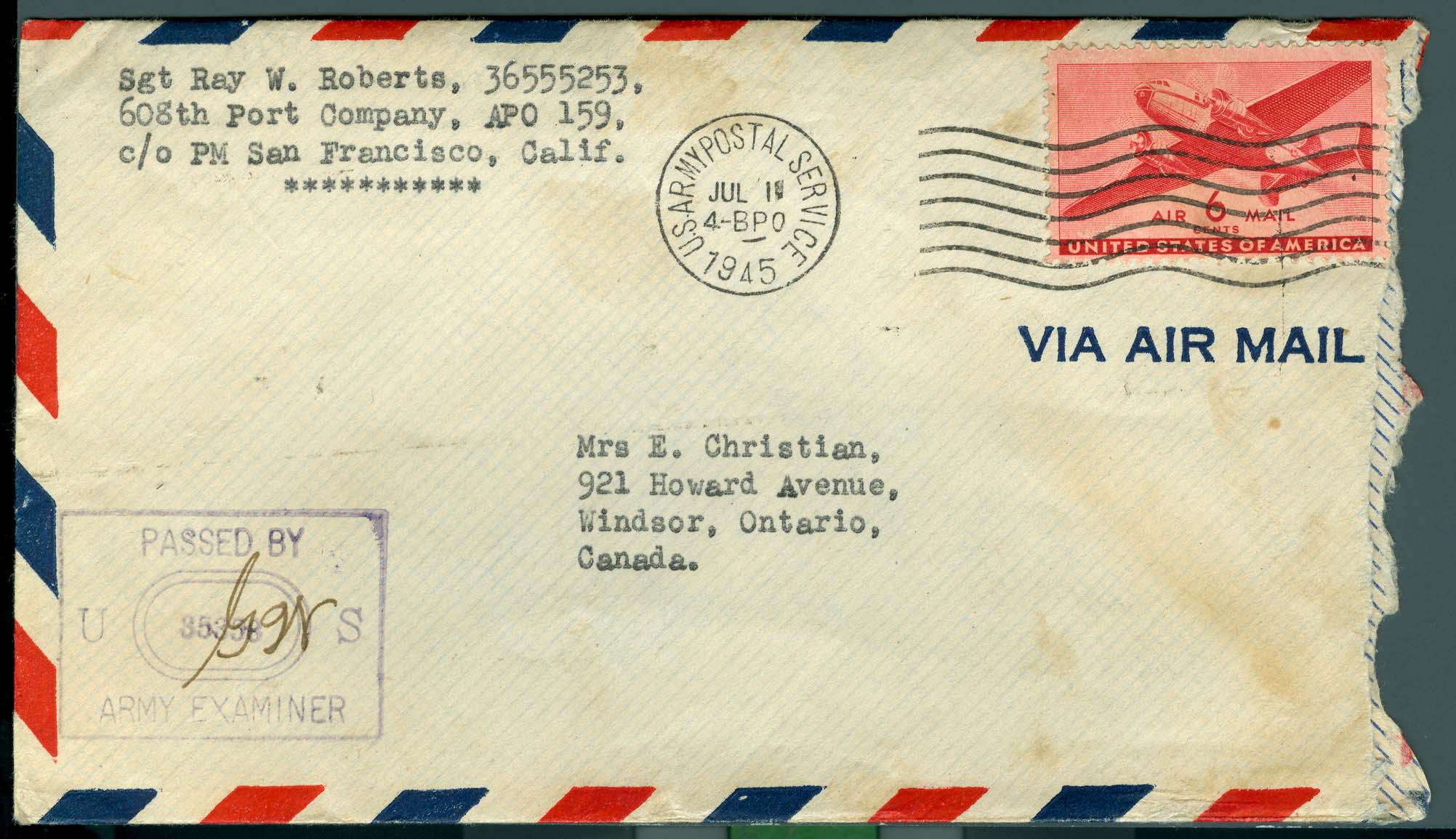

Women of the Corridor routinely organised themselves to address the needs of the community as they arose. During World War II, local women came together to set up the War Mothers’ Protective League, an organisation dedicated to providing Black servicemen with letters of encouragement. The club was especially interested in providing support to those young men from the McDougall Street Corridor who may have lost their mothers and were in need of regular correspondence and upliftment.

President of the club Genevieve Allen and secretary Ethel Christian ensured that Black soldiers received holiday greetings, care and gift packages, along with heartfelt correspondences to keep their spirits high. The club raised funds for these packages by hosting dinners and events through neighbourhood churches like the First Baptist Church and the British Methodist Episcopal Church.

It is hard to estimate the full value of mail from home. Sometimes we don’t receive any mail for a month or more, and you would be surprised at the affect that has on the morale of the company in general. Many of the fellows become skeptical of their home folk and get to the point that they don’t care what happens; but then the dark clouds disappear and the sun shines through — Mail Call.

Members of the War Mothers Protective League sent dozens of letters to Black Canadian soldiers stationed across North America, and those overseas in Belgium, Germany, Holland, France, New Guinea, and the Philippines. The women who wrote letters also received responses from these young men. Their letters not only demonstrate their courage in the face of unimaginable hardship, but also their gratitude for the War Mothers’ Protective League’s heartfelt correspondence and the thoughtfully prepared care packages sent from the home front. Click here to read some of these letters.

The Pivots’ International Club

Another popular organisation, the Pivots’ International Club, brought African Canadian and American women together annually for glitz, glam, and female empowerment. The Pivots’ International Club, a social club for Black women, established its international branch in Windsor in 1963. The club’s first chapter was created in New York City in the mid-1950s, later branching out to Buffalo, NY; Cleveland, OH; Columbus, OH; Detroit, MI; Philadelphia, PA; Pittsburgh, PA; the San Fernando Valley, CA; and Washington, D.C. The Pittsburgh Courier, an African American newspaper, did indicate that a second Canadian chapter was in Toronto, with membership attending from as far as Montreal.

Though information on the Pivots’ is limited to news articles, it seems as though the club was created as an outlet for Black women to participate in community building, education, and social outreach. Similar to other social organisations, the Pivots’ established an annual scholarship program, providing bursaries for Black students across North America. Social events included lavish brunches, luncheons, galas, dances, and fundraisers. An annual club convention was held in chapter cities, with members of each chapter travelling to meet with one another.

In 1966, the Windsor chapter was chosen to organise the first international Pivots’ Club convention. Held at the Prince Edward Hotel, members from across North America gathered to attend various events, including a formal evening ball at the Cleary Auditorium. Over three hundred members and visitors were in attendance, making this the first international Black social club convention held in Windsor. The Pivots’ served a new generation of women seeking to merge activism with glamour and sisterhood with social outreach during the mid-twentieth century.

Windsor’s chapter was led by international vice-president Velma Vincent. A life-long resident of the McDougall Street Corridor, Velma was active in many of Windsor’s Black organisations, serving as president of the Armstead Athletic Club; secretary of the Central Citizens’ Association; and superintendent of the B.M.E. Sunday School at various times. Vincent also managed multiple businesses in Detroit. Records of the Pivots’ Club in Windsor are limited, and it appears the club may have ceased activity by the late 1970s.

Other Clubs

The Armstead Athletic Club

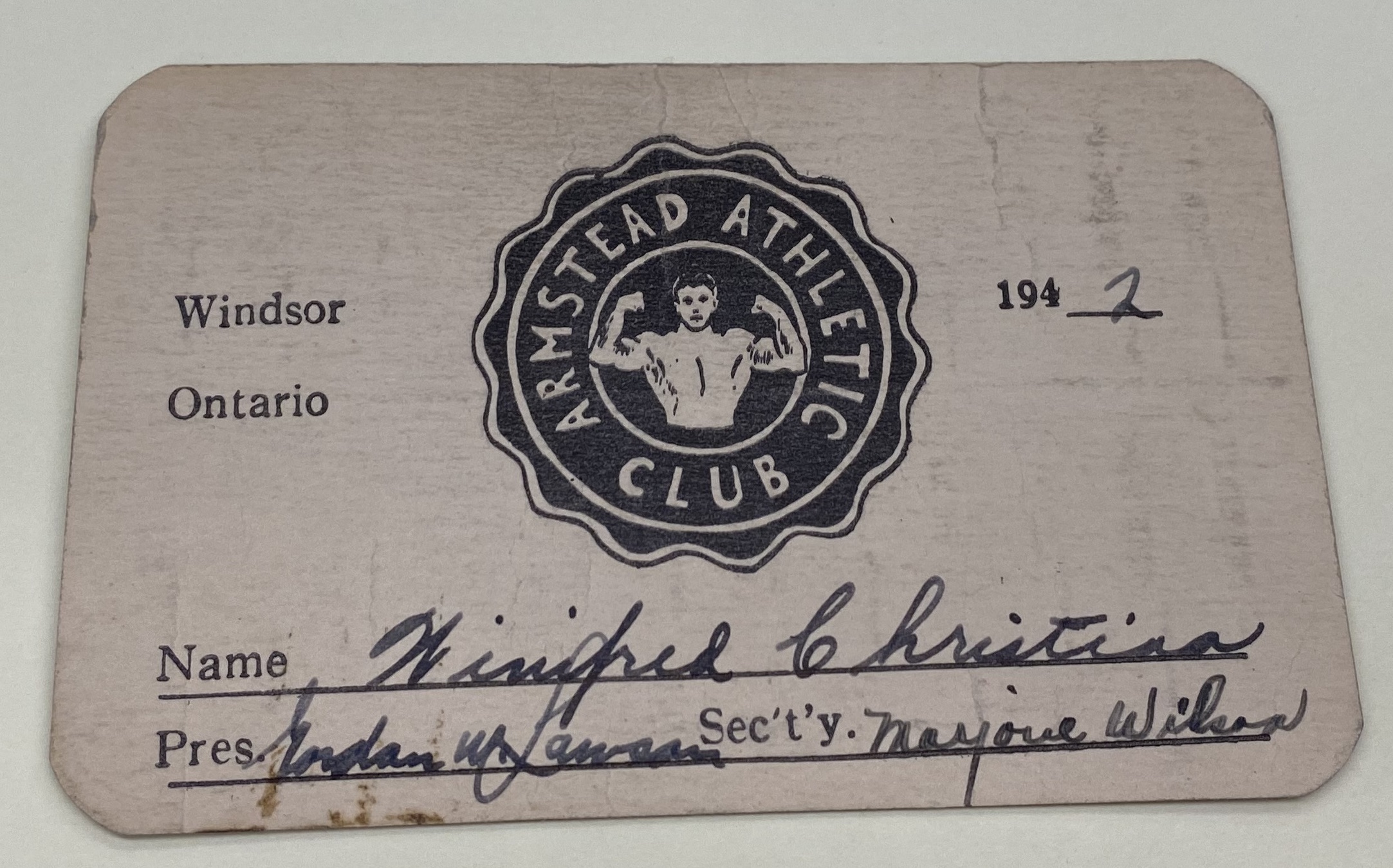

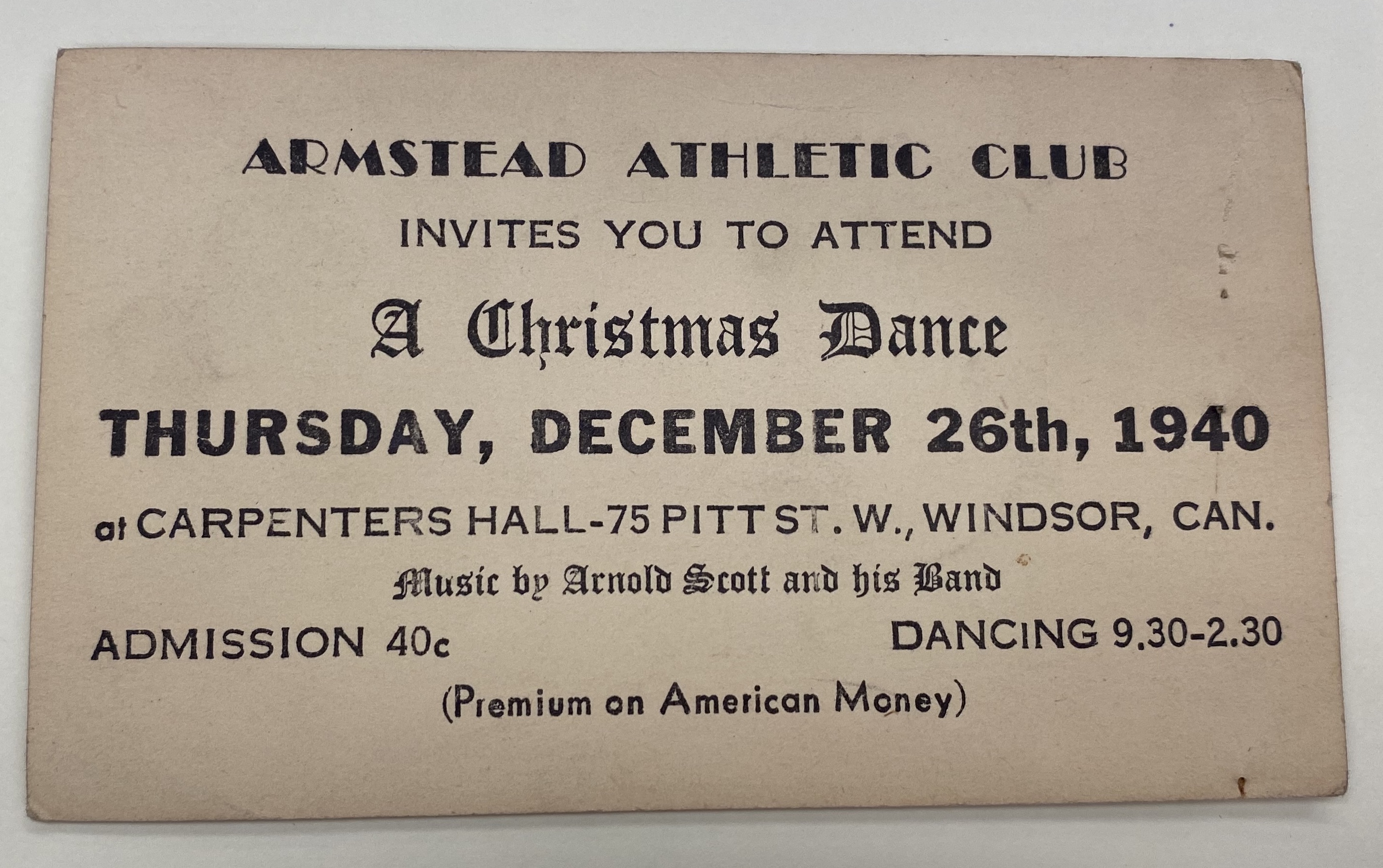

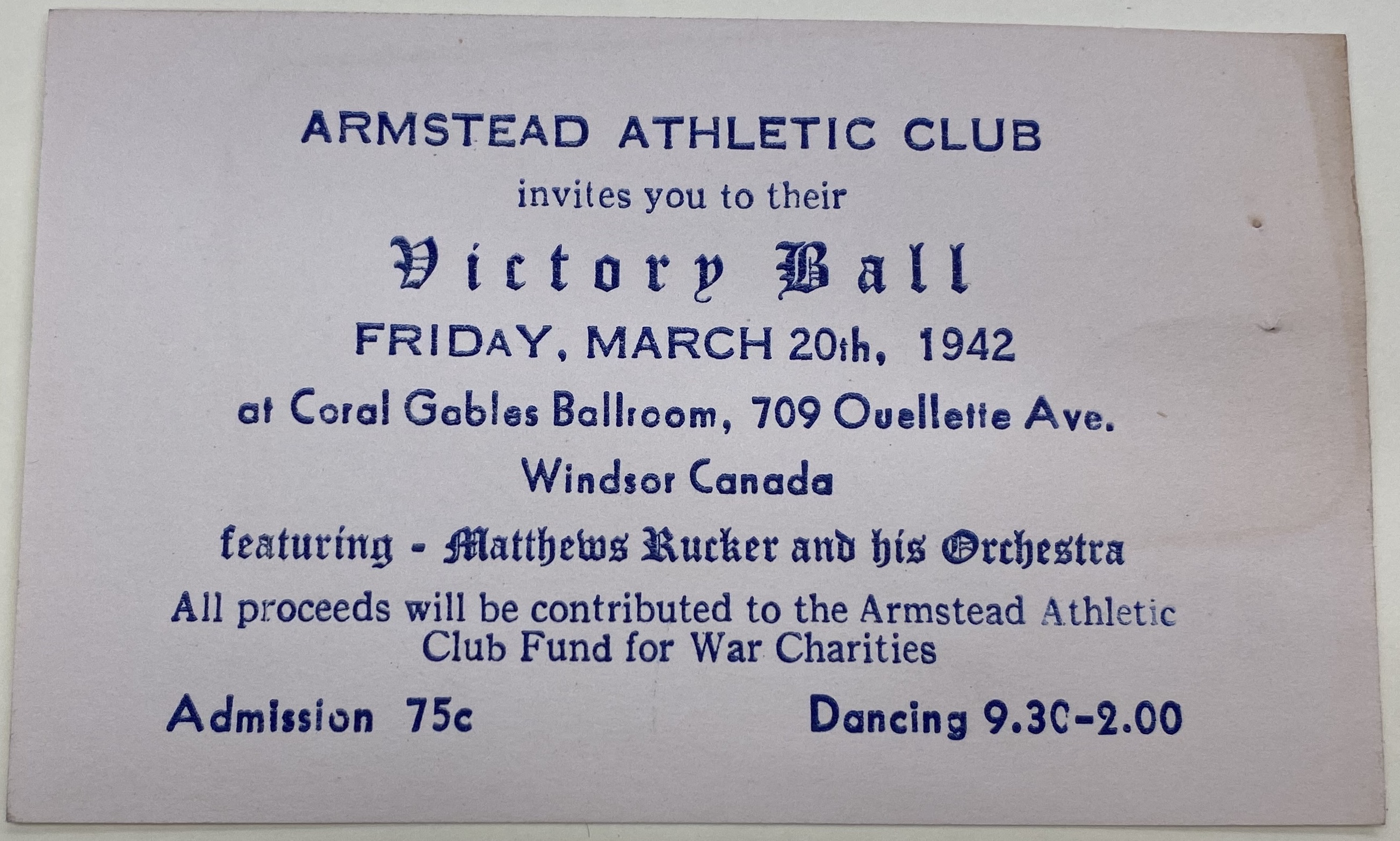

The Armstead Athletic Club gained inspiration from a local group of young women with an interest in pursuing athletic and leisure activities in the McDougall Street Corridor. Illa Harrison, Theresa Harrison, Winifred Shreve, Agnes Sopher, and Marie Thompson created the Armstead Tennis Club in the late 1930s to address the limited access to leisure spaces in the city. Attracting the interest of notable residents like Dr. Roy Perry, Dr. Gordon Lawson, Velma Vincent, and J. Lyle Browning, the Armstead Athletic Club was established as a co-ed group in 1940. The club’s name honoured local resident Armstead Taylor, the father of Dr. Henry D. Taylor.

Like many of Windsor’s Black organisations, the Armstead Athletic Club battled racial discrimination in their work to procure spaces for residents of colour to participate in equal measure. After being barred from playing Tennis in Jackson Park, club members established several tennis courts throughout the Corridor for Black residents to use. One such court was located on McDougall Street where the second home of Tanner African Methodist Episcopal Church would be built following their expropriation.

While the first few meetings were held at the home of president Dr. Roy Perry, as well as the shared offices of Dr. Perry and Dr. Taylor on Wyandotte Street, the club later held its monthly meetings at the barbershop of Mr. Joseph Browning at 592 Wyandotte Street East. Club membership and participation was limited to just thirty people but included amateur athletes from Windsor-Essex and Detroit. The Armstead Athletic Club hosted guest speakers from across North America, including Olympian Jesse Owens who, in May of 1944, spoke to members about, “The Importance of Athletics, Especially During Wartime,” while he was living and working in Detroit.

Over the course of two decades, the Armstead Athletic Club served residents of the McDougall Street Corridor by promoting physical activity and charitable endeavours. Along with hosting fashion shows, luncheons, galas, and live performances for the community, the club held an annual Scholarship Bridge, raising funds for their scholarship program that supported Black students of Windsor-Essex with bursaries for the purposes of pursuing higher education. It appears the club ceased operations by the mid-1960s.

British American Association of Coloured Brothers of Ontario

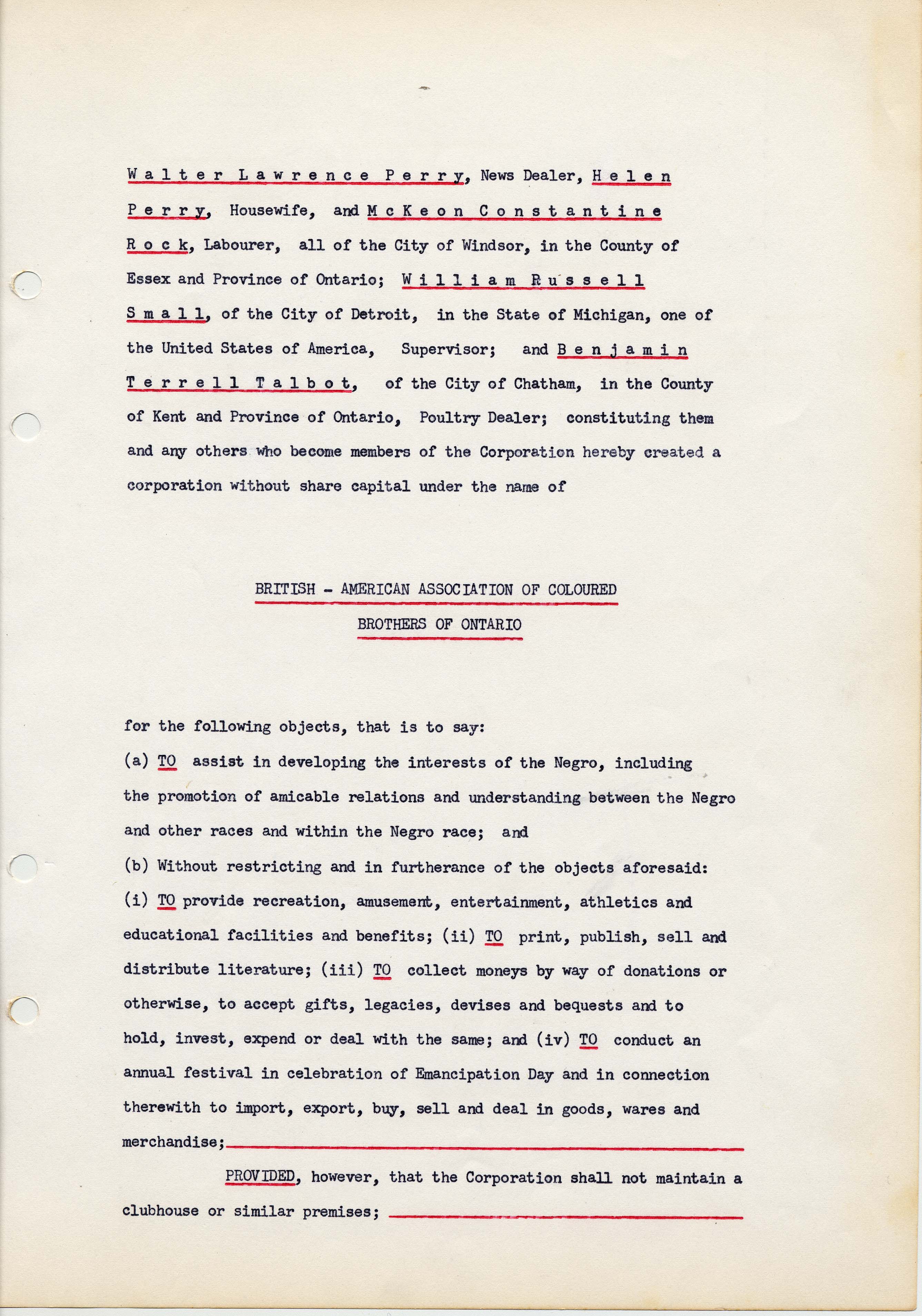

In 1935, the British American Association of Coloured Brothers of Ontario (BAACB) was established in Windsor as the official organiser of the annual Emancipation Day Celebrations.

Organised by Walter Perry, who was also known as “Mr. Emancipation,” this multi-day event celebrated the emancipation of peoples of African descent within the British Empire.

Beginning in 1931, McDougall Street resident Walter Perry ushered in a new era of Windsor’s Emancipation Day celebrations. Perry’s many connections with performers, prominent speakers, and vendors transformed this already popular event into one with international status. Prior to Perry’s involvement, Emancipation Day celebrations often alternated between Windsor, Sandwich, and Amherstburg, with the aid of various organisations including the Freemasons and Oddfellows. While popular amongst Black Canadians, through Walter Perry’s effort Emancipation Day became an event attended by Windsorites of all backgrounds. Adding to its popularity were the thousands of international attendees from across the United States. During the celebration’s height in the 1940s and 1950s, Windsor would see almost a quarter of a million visitors.

Under the auspices of the BAACB, Progress Magazine was created as a guide to the yearly Emancipation Day celebrations held in Windsor. The magazine outlined the annual program, including the various guests, contributors, and sponsors. Starting on the first of August, the celebration included a parade travelling from Riverside Drive East to Jackson Park, where a carnival consisting of fair rides, games, contests, food vendors, and performers was stationed. The parade often included Canadian and American marching bands, drill teams, and the floats of local businesses and organisations. Images from the celebrations are available by clicking this link.

The Miss Sepia Pageant, the first international Black beauty pageant, was created by Walter Perry in 1931 and was a highlight of the performances and activities at Jackson Park.

The popularity of Walter Perry’s annual event also caught the attention of prominent musicians, athletes, and entertainers including actress Dorothy Dandridge, Olympian Jesse Owens, boxer Joe Louis, as well as artists like Diana Ross and the Supremes, the Temptations, and Stevie Wonder.

By the mid-1940s, the organisation became involved in the fight against anti-Black racism by engaging with civil rights activists and community leaders from across North America. Leaders and activists who participated as guest speakers included Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth, Adam Clayton Powell, and Myrlie Evers, the wife of the late civil rights activist Medgar Evers.

With the help of the International Women’s Committee, a joint Detroit-Windsor Black women’s organisation, Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune and Eleanor Roosevelt were invited to Windsor’s Emancipation Day celebration as guest speakers in 1954.

The BAACB routinely awarded residents, social organisations, and politicians for their contributions to the Black community. Famed Windsor writer Richard M. Harrison received the Freedom Award from the BAACB in 1951 for his consistent reporting of issues within the McDougall Street Corridor, such as housing and employment discrimination.

Soon after the BAACB began interacting with leaders of the growing civil rights movement, the city began sponsoring the International Freedom Festival, while simultaneously withdrawing support for the Emancipation Day celebrations. The International Freedom Festival, set one month before Emancipation, was a joint celebration for Canada Day and America’s Independence Day. It was also used as an opportunity for both Windsor and Detroit to complement their urban renewal strategies with increased tourism.

By the early 1960s, it was clear to the organisers of Emancipation Day that the city wanted to promote the Freedom Festival as Windsor’s primary summer event.

Emancipation Day would continue until 1967, when the event was cancelled following the Detroit Uprising. Walter Perry passed away later that year.

When the BAACB, under the leadership of Ted Powell, inquired about the carnival and parade permits in 1968, they were denied by Windsor’s police commission as it was “feared the racial trouble in Detroit might spill over into Windsor,” if the celebration were to be held again. The parade permit was later granted, but the carnival was not. The city however, had no plans to cancel the Freedom Festival, stating they were not anticipating any problematic activity from that event.

This forced cancellation at the hands of Windsor’s police commission was seen as a deliberate attempt to stifle the annual event. In response, Emancipation Day organisers contacted the Ontario Human Rights Commission. Community leaders from Windsor and Detroit and representatives of the Guardian Club, the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, and the United Auto Workers held a commemoration service in Windsor to address the cancellation of Emancipation and call for the Ontario legislature to amend the powers of the police to grant licences for public gatherings.

Emancipation Day celebrations would be reinstated in 1969, but the two year hiatus, limited funds, and the city’s relocation of the event to Mic Mac Park led to dwindling crowds. By the 1980s, Emancipation was relocated to Amherstburg.