We Were Here and the Archives, Dr Sarah Glassford

A Place on the Map, A Place in History: Historical Erasure and the McDougall Street Corridor

Dr. Sarah Glassford

Since the rise of industrial cities in the nineteenth century, urban landscapes have been sites of unceasing change: individual buildings, roads, green spaces, and entire neighbourhoods are built up, torn down, repurposed, abandoned, and/or revitalized in response to shifting social, economic, political, and cultural currents. History, too, is constantly in flux. The stories we tell ourselves about the past, the people at the centre or periphery of those stories, and the events or ideas we consider worthy of study or commemoration, change over time in response to the interests and needs of the present.

Now You See It… Now You Don’t

Windsor, Ontario’s historically-Black McDougall Street Corridor demonstrates the changing nature of both cities and historical narratives. McDougall Street remains a real place in the city and on its maps, but the physical infrastructure and community of people, businesses, and institutions that once thrived there has largely been erased from the visible landscape. The physical destruction of the geographical place and dispersal of its people was echoed for many decades in its effective erasure from the history of Windsor. Those who had been part of the community held their memories of it close, but its story – and with it, the roles played by African-descended peoples in the larger history of Windsor – fell off the radar for the broader population. The physical world of the Corridor now exists as a kind of “present absence.” As soon as we know that something should be there but is not, our attention is drawn to its absence – and in the process, to the powerful forces that did their best to erase and replace it. In other words, once we recognize the potent combination of mid-twentieth-century urban redevelopment idealism and deep-seated anti-Black racism that erased the Corridor community, we cannot unsee it. Weed-ridden vacant lots begin to feel more like ghost-towns.

Who Is “Historical” and Who Are the Historians?

It is no accident that more than half a century passed between the destruction of the McDougall Street Corridor and this project’s work to commemorate it. Rather, it reflects the shifting nature of History as a formal area of study, and Canadians’ changing conceptions of whose stories matter. As new types of people began researching and writing history, they brought new approaches and an interest in new subjects, determined to see their own experiences, and those of people like them, better reflected in our shared narratives of Canada’s past.

As a profession and as a modern area of study, History has evolved enormously over the past century-plus. Its nineteenth-century European founders established their field of study as one focused on telling the stories of (primarily European) empires and nations and their (principally male) leaders, in the realms of politics, economy, ideas, and war. History was about power and conquest, political machinations and ideologies, economic progress, and the rise and fall of empires and nation-states. Most often, it was the story of powerful white men governing and/or fighting with a whole lot of other people. In turn, these approaches infused the stories twentieth-century Canadian schoolchildren (ie. future leaders and voting citizens alike) imbibed from their history textbooks: stories in which white Europeans (first French, then British) discovered and settled the northern part of North America, and Canada emerged as a dutiful white settler colony proudly nestled within a benevolent and civilizing British Empire. There was little space for women, children, and non-British-or-French-descended peoples, for subjects outside of politics, economy, and war, or for the harsh realities of what it meant to be colonized, enslaved, or otherwise disenfranchised, disempowered, and oppressed.

This situation began to change in the 1960s and 1970s. New waves of non-white immigration began to alter the country’s demographics, while older groups of settlers – notably French-Canadians and non-British/non-French European immigrant communities like Ukrainian-Canadians – began to demand more recognition as part of the country’s history and present-day social fabric. Black Power and Red Power activism respectively channelled the frustrations of African-descended and Indigenous peoples marginalized by entrenched and institutionalized racism. Second Wave feminism and Gay Rights mobilized women and 2SLGBTQIA+ people against gender and sexuality-based oppression. Much, although by no means all, of this social ferment was spurred by the large and vocal population of Baby Boomers who had reached young adulthood and were determined to use their voices and numbers to protest injustice on many fronts.

In the context of these massive cultural shifts, a new generation of “social historians” emerged, challenging the status quo by examining history “from the ground up.” Social historians began by researching and telling the stories of working-class people and local communities in meaningful ways for the first time, altering and enriching our understandings of the past. From the 1970s to the present, this broad interest in ordinary people has inspired the creation of more and more new branches of History: women’s and gender history, Black history, Indigenous history, Queer history, the history of immigration and of specific national or ethnic groups within immigrant populations – and on, and on. In Canada, those who study History remain predominantly white, but each passing decade brings new diversity – and therefore powerful new perspectives – to the ranks of both professional and amateur historians.

What Is in the Archives and Why Does It Matter?

While historians charged ahead, asking new questions and innovating new techniques in order to answer them, for a time museums and archives lagged behind, still saddled with collection mandates and ingrained attitudes that privileged the stories of governments and elites. In time, however, (spurred in part by the insistence of marginalized peoples and communities that their histories are also worthy of preservation and sharing) museums and archives revisited and revised their policies, approaches, and collections with an eye to better reflecting the complex array of stories of which Canadian history is composed. By the end of the twentieth century, the lives of the people who lived along the McDougall Street Corridor were considered properly “historical” in a way that would not have been true in earlier periods. Now, as the twenty-first century unfolds, we can increasingly study communities like the McDougall Street Corridor because museums and archives have acquired – or simply better described and identified – records, images, and artifacts that document their inhabitants’ presence.

Who writes history, and what sources they have to draw from, matters enormously, because whether we recognize it or not, the past shapes the present and future. As a society, Canada has inherited from decades and centuries past a heavy burden of racism, sexism, class inequity, ableism, and discrimination against linguistic, religious, gender, and sexual minorities. This legacy is written into the stories we tell ourselves about who built and shaped this country, whose experiences of it are important, and what that means for how we live together today. The faces and voices we encounter in museum exhibits, on public statues, and in history books join those we see and hear in modern media to quietly shape our understandings of who belongs or matters… and who does not. These assumptions in turn shape real-life actions, from government policies to people’s daily interactions with one another.

Writing McDougall Street Back into History

In its heyday, the McDougall Street Corridor was home to a thriving, predominantly-Black community. Not a wealthy one, but a vibrant one, populated by hard-working people who helped to make their city what it was. This community was destroyed within living memory because it was seen as too poor, too Black, and too inconveniently-placed to fit into the vision city leaders had of a revitalized mid-century modern city centre. For Windsor to shake off its inheritance of anti-Black racism, it is important for all Windsorites to recognize the “present absence” that is the Corridor community. We begin the work of writing McDougall Street and its people back into the history of Windsor when we notice, first, that it is missing.

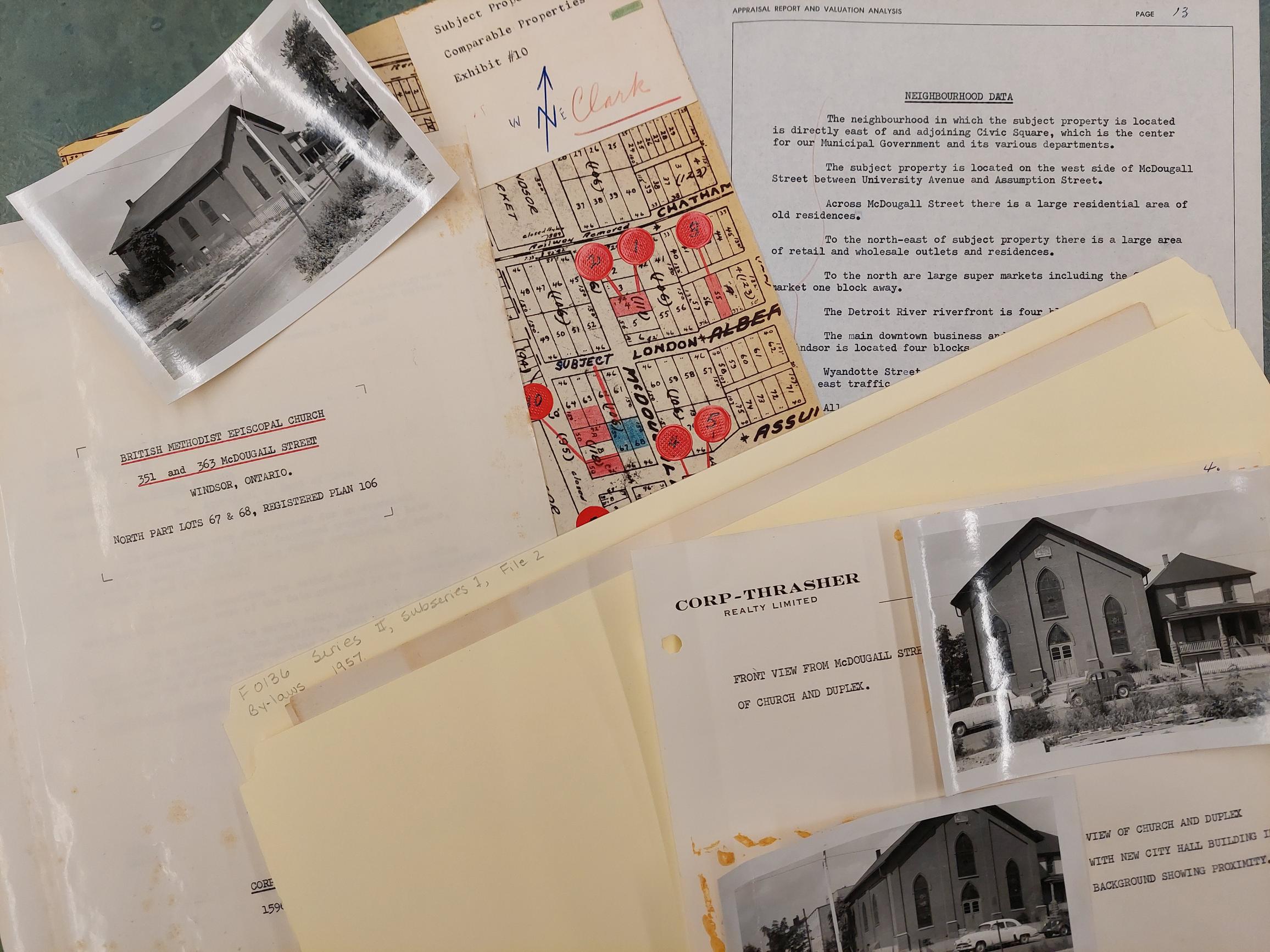

Researching the physical place – gathering traces of the Corridor still evident in old maps, city directories, photographs, government documents, and human memory – is a reclamation of historical space. The images, documents, artifacts, and interviews now assembled in this web portal are not here by accident. Instead, they are the product of a conscious decision to reconstitute the McDougall Street Corridor and the Black lives it nurtured and reflected, in a new, virtual space. In doing so, we take another step toward reinscribing the Corridor into the history of Windsor.

The stories we tell about our shared past as a city are powerful. Racism married to an ideology of urban redevelopment erased the McDougall Street Corridor community from the landscape of downtown Windsor. But through the power of History and storytelling – our ability to dig into the archives, interview eyewitnesses, analyze what we find, curate, narrate, and share it in the public sphere – we claim space and significance for the Corridor and its people once again.