McDougall Street Corridor: An Overview

By Willow Key

While the names and faces of influential Black Canadians are recognisable to many, few Canadians are familiar with the communities that helped to nurture and support these figures.

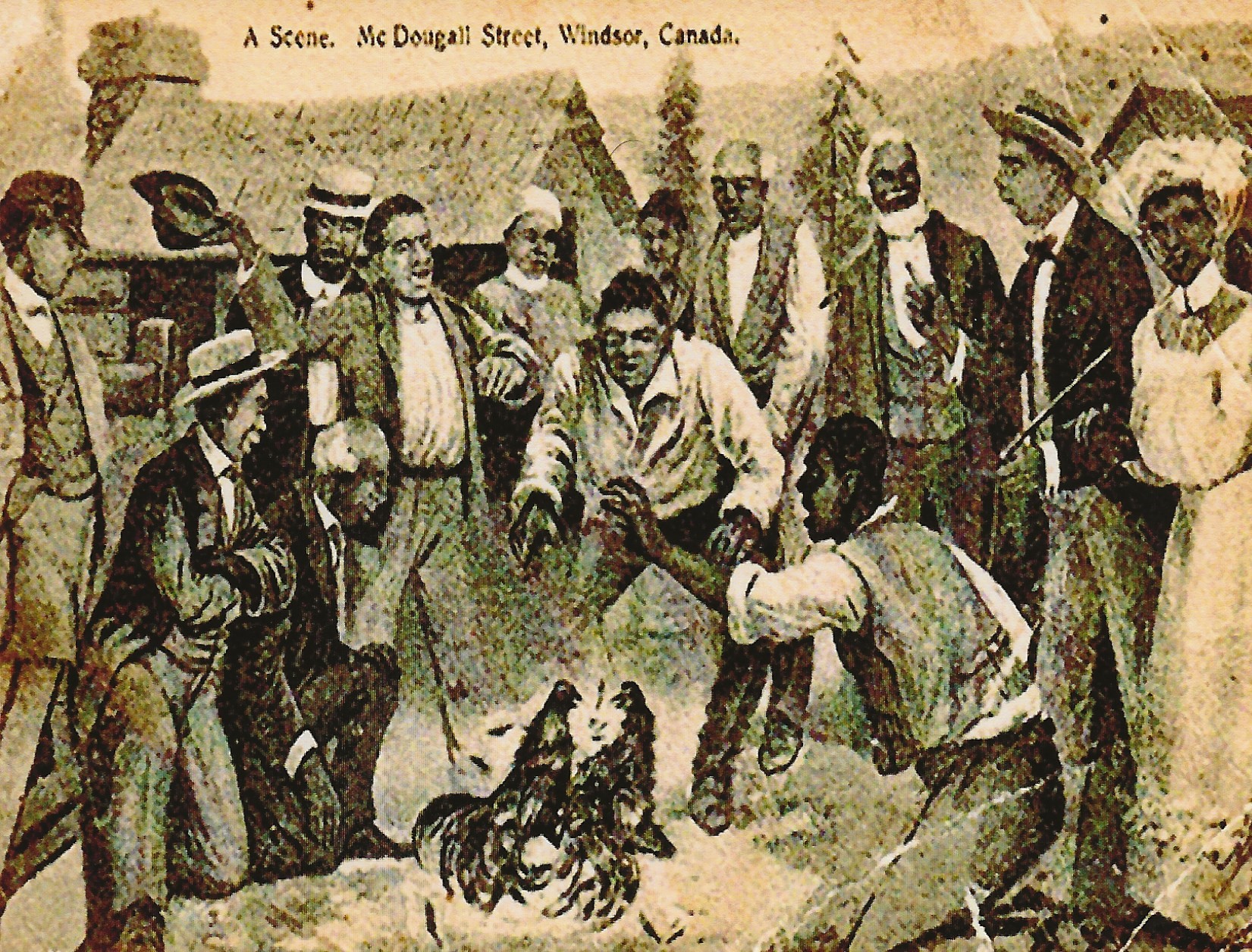

Community has always been central to the African Canadian experience. Without community, the social constraints and hardships that are part and parcel of the Black experience are made an even greater challenge. Black Canadians and the spaces they inhabit have long been viewed as static and positioned firmly in the context of the nineteenth century. This perspective, however, ignores a vibrant history that continued throughout the twentieth century and one that is still present today.

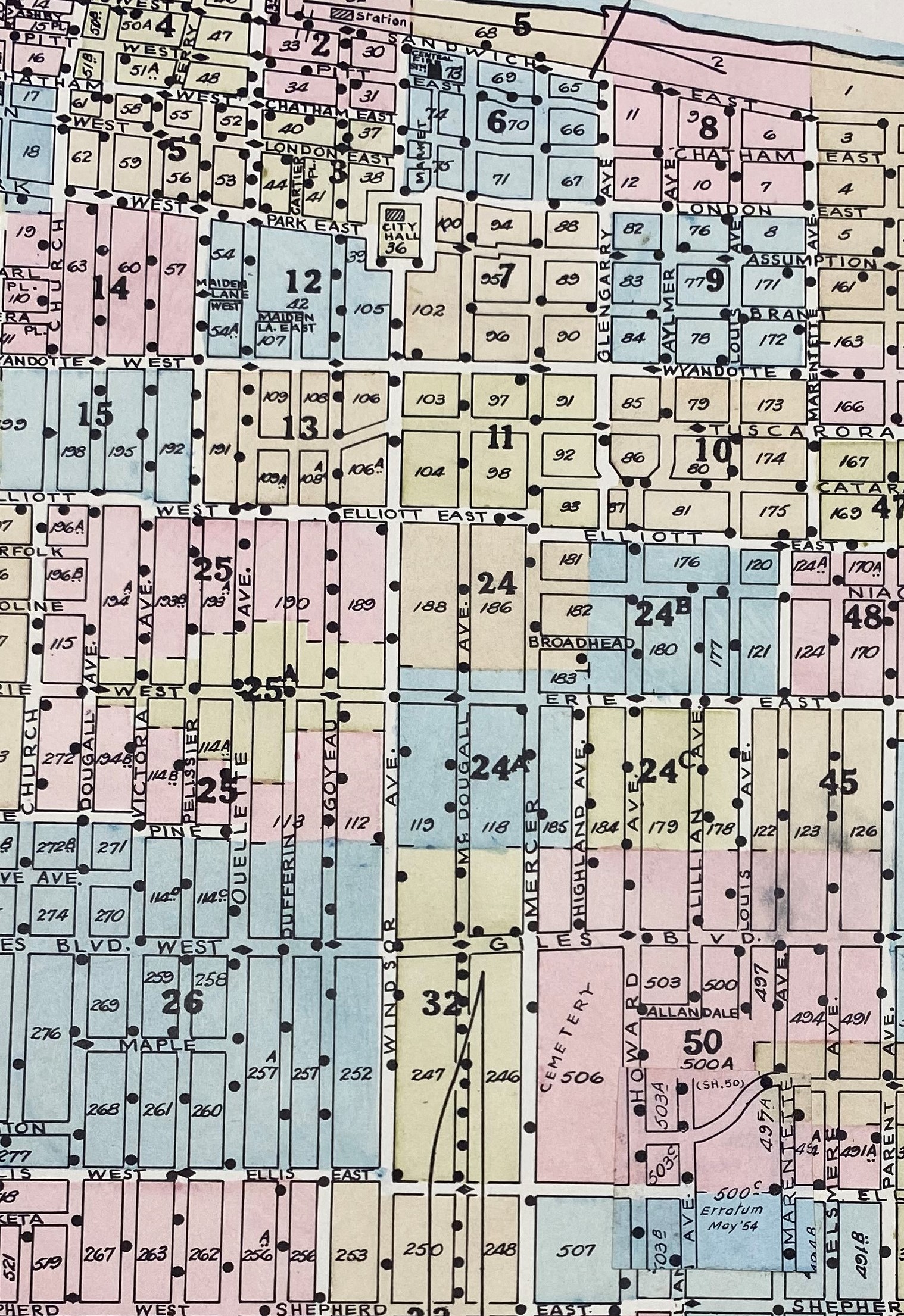

Windsor, like most major cities across Canada, was home to a dynamic Black community located in the metropolitan core. Situated to the east of the commercial district, the McDougall Street neighbourhood was a mostly self-sufficient African Canadian community bound on the north by what is now Riverside Drive East, on the west by Goyeau Street, on the south by Giles Street East, and the east by Howard Avenue. The McDougall Street Corridor is named for one of Windsor's oldest streets, McDougall, which runs through the centre of this neighbourhood and was once the heart of the Black community.

The beginnings of the McDougall Street Corridor

Following the passing of the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, which abolished slavery across most of the British Empire by the following year, Windsor quickly became a haven for African Americans escaping bondage in slave-holding states. When free Blacks in the United States were threatened with enslavement or recapture through the passing of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, thousands more freedom seekers and free people of colour found refuge in towns and villages across Southwestern Ontario, including the McDougall Street Corridor and nearby Sandwich Town.

Upon arrival in Windsor, essential care and temporary lodging were provided to freedom seekers in the city’s military barracks, where Windsor’s City Hall Square is today. The barracks served as a waystation and one of Windsor’s final stops along the Underground Railroad, caring for those who had survived the long and arduous journey.

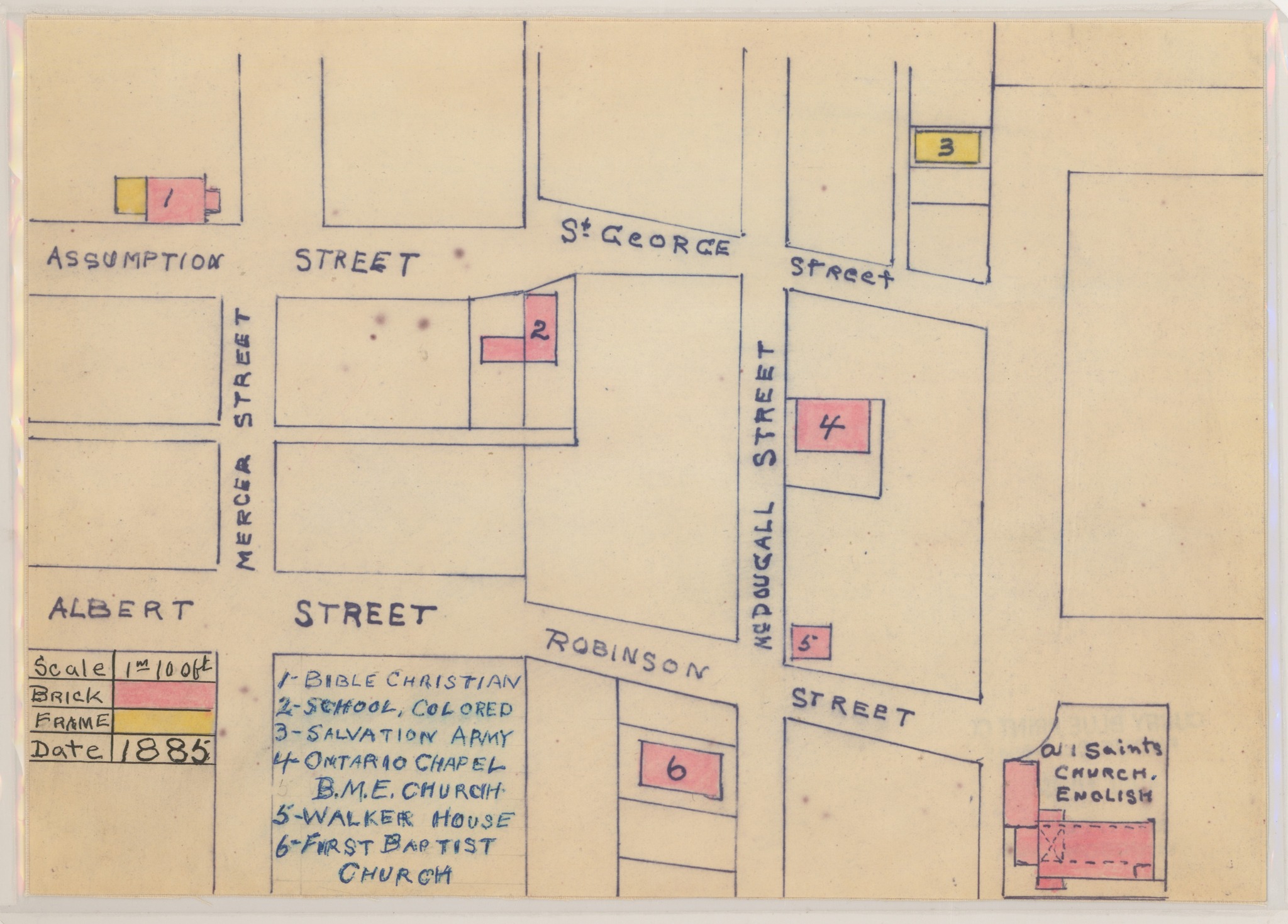

Fearing the possibility of recapture so close to the border, most freedom seekers passed through Windsor on their way to other towns and communities further inland. Some chose to stay in the city however, settling around the barracks along Windsor Avenue and McDougall and Mercer Streets, between the Detroit River and Wyandotte Street. This area became the nucleus of the McDougall Street Corridor.

McDougall Street Neighbourhood in the Twentieth Century

Over the next century, Windsor’s Black community would expand beyond the initial boundaries of the McDougall Street neighbourhood, moving further south toward Erie Street.

While Black immigration from the United States quickly declined following the Civil War and the abolition of slavery, in the early twentieth century the population of Windsor’s Black community increased in part from the movement of those from rural areas into Windsor for industrial and manufacturing work, particularly in the years of World War II.

Those who settled in the McDougall Street area founded five prominent churches, many businesses, social organisations and halls, and educational institutions. This thriving community found creative ways to address and combat the discrimination they faced as a people, while supplying the much-needed services they were often denied access to across the city. The Walker House Hotel catered to Black Canadians and African Americans with safe lodgings as Windsor’s premiere Black-owned hotel; the Mercer Street School served the community as a popular location for Black educators and students to thrive; and the needs of the community were often addressed by one of the five churches in the area, such as the British Methodist Episcopal Church and First Baptist Church. These institutions are amongst the oldest and most dynamic spaces in the city.

By 1941, Windsor’s Black population numbered more than one thousand. The community was extremely close-knit, many families in the area were related or connected through marriage, with the McDougall Street neighbourhood functioning as a landscape of extended families. The neighbourhood served as a safe place within a city that was not always accommodating or kind to those of African descent.

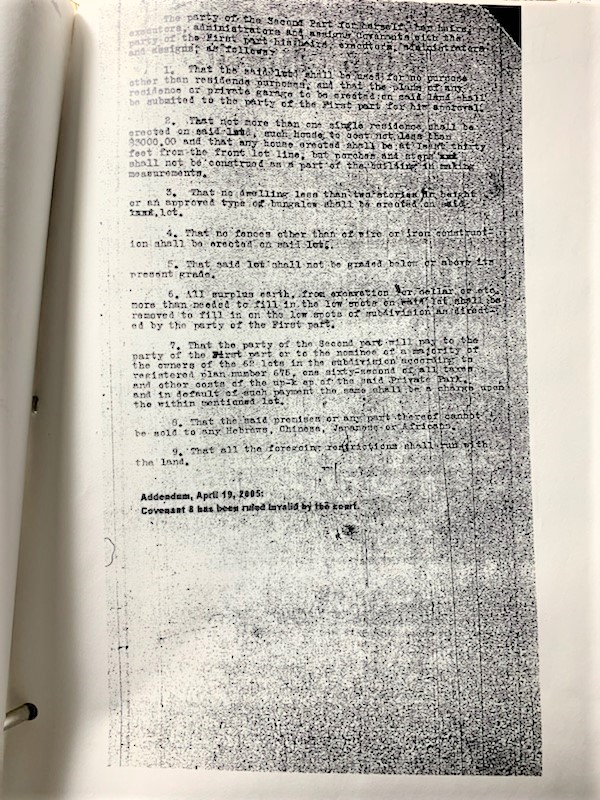

The neighbourhood also served as a reminder of the second-class status applied to Black Windsorites. Housing discrimination was present within the city until the late 1960s, especially in the form of informal restrictive practices and racially restrictive covenants. This practice resulted in there being very few neighbourhoods in the city where Black residents could rent or purchase homes. These discriminatory housing practices kept Black families in the McDougall Street area and restricted their movement into other areas. It also meant housing for Black Windsorites was limited, resulting in overcrowding, and turning single family homes into multi-family dwellings in the area. While residents would spend decades advocating for the removal of racially restrictive housing practices, these policies would have long lasting ramifications that continue to affect those of African descent today.

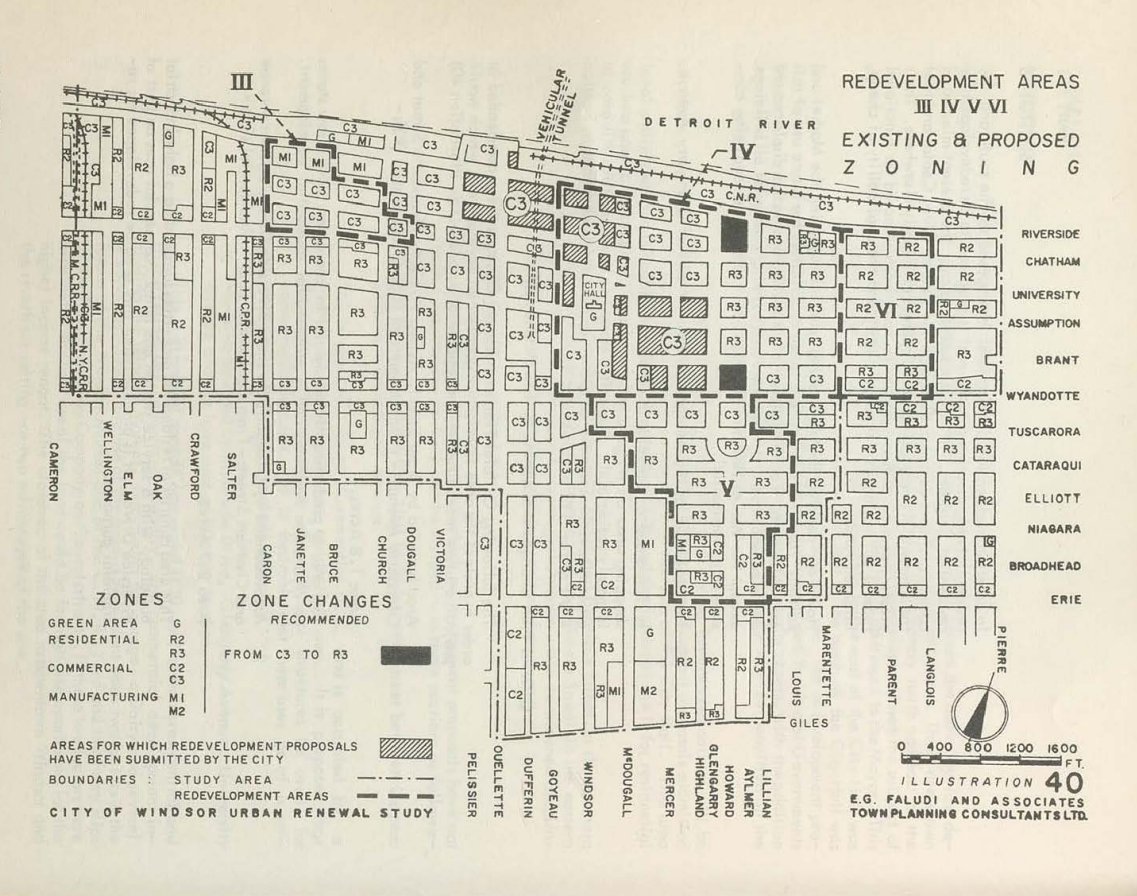

Urban “renewal” and the McDougall Street Corridor

A 1957 survey conducted by the Windsor Interracial Council recorded approximately 250 Black families living within this neighbourhood. It was also in 1957 that the City of Windsor began funding research for an aggressive urban renewal program. Like many Black communities during this period, the McDougall Street Corridor fell victim to urban renewal planning, a widespread practice in postwar North America. All levels of government played a role in facilitating the razing of neighbourhoods that were considered “blighted” or “slums”, often resulting in the uprooting of working-class families and communities of colour in the process.

The first of these redevelopment projects in Canada took place in the early 1950s with Toronto’s Regent Park neighbourhood. This process of urban transformation would be reproduced in cities across the country by mid-century; most notably Halifax’s Africville community in 1964. In the United States, similar projects saw the destruction of Black communities like Detroit’s Blackbottom and Paradise Valley neighbourhoods, Chicago’s Hyde Park, and South Carolina’s Wheeler Hill.

In conjunction with federal policies, Windsor’s postwar urban renewal program destroyed historic churches, social halls, and multigenerational homes in the name of progress and modernization. Within a few years, century-old buildings constructed by freedom seekers and their descendants disappeared from Windsor’s landscape.

The physical destruction of Black spaces within the McDougall Street area broke many social and familial bonds and resulted in the loss of Black land ownership and community organising power.

The stories shared by Black Windsorites throughout We Were Here, however, are a testament to the resilience of the McDougall Street community, all that they have accomplished, and all that they have lost in the name of “progress.”