Black Businesses and Professional District

By Willow Key

Windsor’s Black business district emerged swiftly after the settling of the McDougall Street Corridor. Grocery stores, confectionery shops, printers and newsstands, tailors, hairdressers, and restaurants were among the many services dotting the streets of this neighbourhood.

Professions in the Corridor were varied and included engineers, tradesmen, dock workers, postal workers, educators, and labourers. While much of the northern portion of this neighbourhood consisted of mixed-use residential and commercial buildings, many popular Black storefronts were located along McDougall Street, Wyandotte Street East, and further south near Erie Street.

Self-reliance was essential for this community. As mentioned throughout this digital exhibit, Black Windsorites were often restricted from patronising certain businesses and services across the city. In response, a network of formal and informal shops and services were established within the community to address the needs of residents and allow them to shop and request services with dignity. Additionally, many providers of these services found employment within their community to be easier to obtain than the menial, low paying positions provided to people of colour by large corporations and industries throughout the city. Black business owners also made an effort to employ members of their community, ensuring the success of these businesses and the community at large.

Early Businesses in the McDougall Street Corridor

Early businesses such as the J. L. Dunn Paint and Varnish Co., Hyatt Green Houses, and the Alberts Steam Cleaning and Pressing Plant are but a few in an extensive list of independent Black-owned and -operated businesses that have existed throughout Windsor’s downtown core since the mid-nineteenth century.

Roles for women were often limited, but those who could carve out a place for themselves established successful businesses of their own. Mary Ann Shadd Cary’s The Provincial Freeman, published in Windsor for a time, was the first newspaper to be published by a Black woman and the first to be published by a woman of any ethnicity in Canada. Understanding the need to connect Ontario’s Black communities through news and correspondence, Shirley Moore of Mercer Street established a newsstand selling London’s Dawn of Tomorrow.

Hotels, Restaurants, and Entertainment

One of Windsor’s premier Black businesses was the Walker House Hotel. Built in the mid 1880s at the corner of McDougall Street and University Avenue, this hotel was first owned and operated by Edward Walker. Noted as a Black merchant in the census, he was the grandfather of Hour-a-Day Study Club founding member Anna Ardella Jacobs. The Walker family managed the hotel for more than two decades before it was purchased by brothers George and John Alexander Smith, who continued the hotel’s operations for fifty-five years.

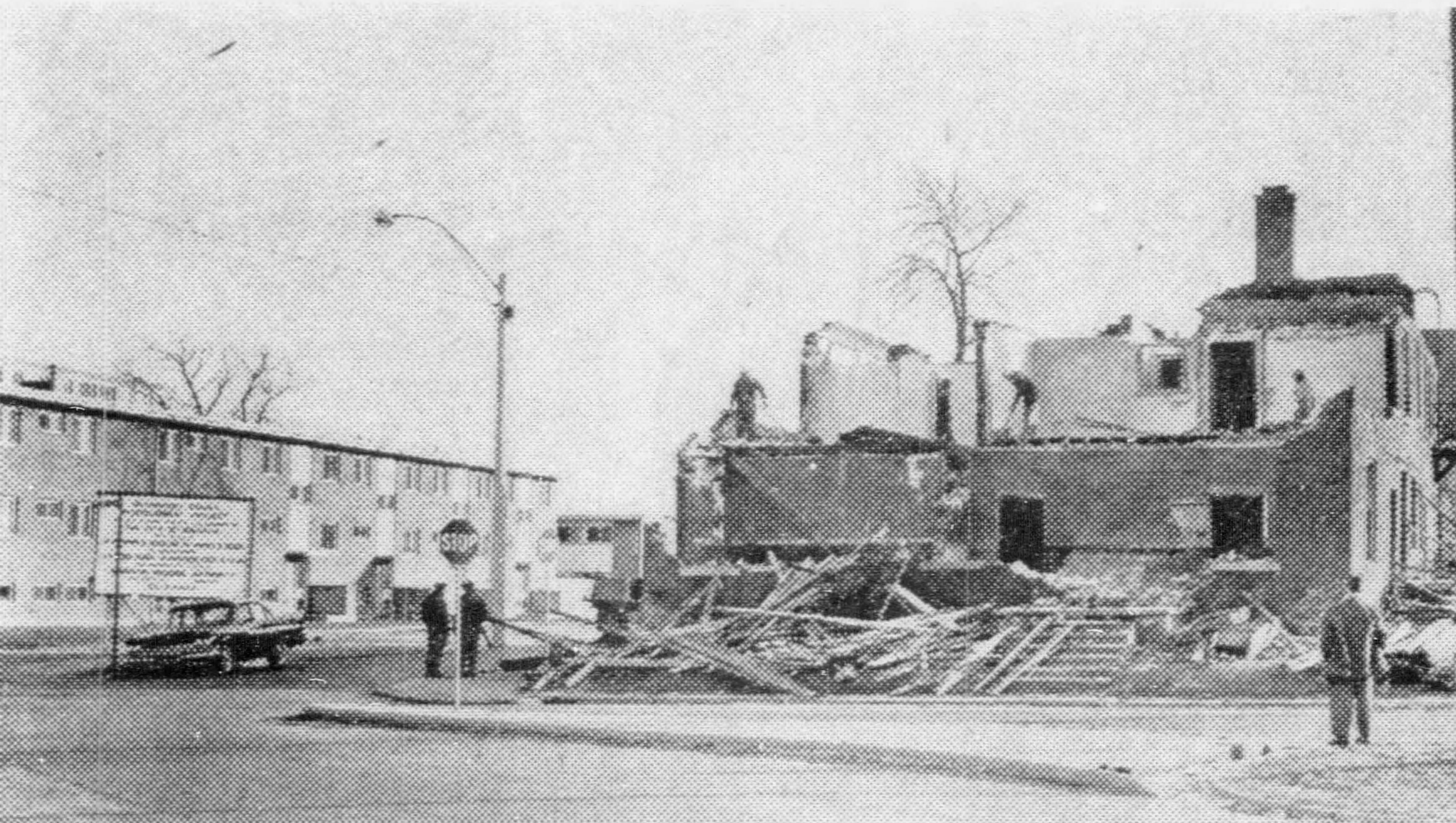

Hotels like the Walker House were essential for Black travellers during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as it was often very difficult to find clean and hospitable accommodations that would accept Black patrons. The hotel offered comfortable lodgings, warm meals in the dining area, and entertainment in the beverage room and bar. For Black Canadians and Americans, the Walker House Hotel allowed them to travel with dignity and freedom. The Walker House Hotel also served the Black community as a popular meeting place for social organisations and political rallies. Unfortunately, the hotel was expropriated by the city and demolished in 1961 for the purposes of a parking lot.

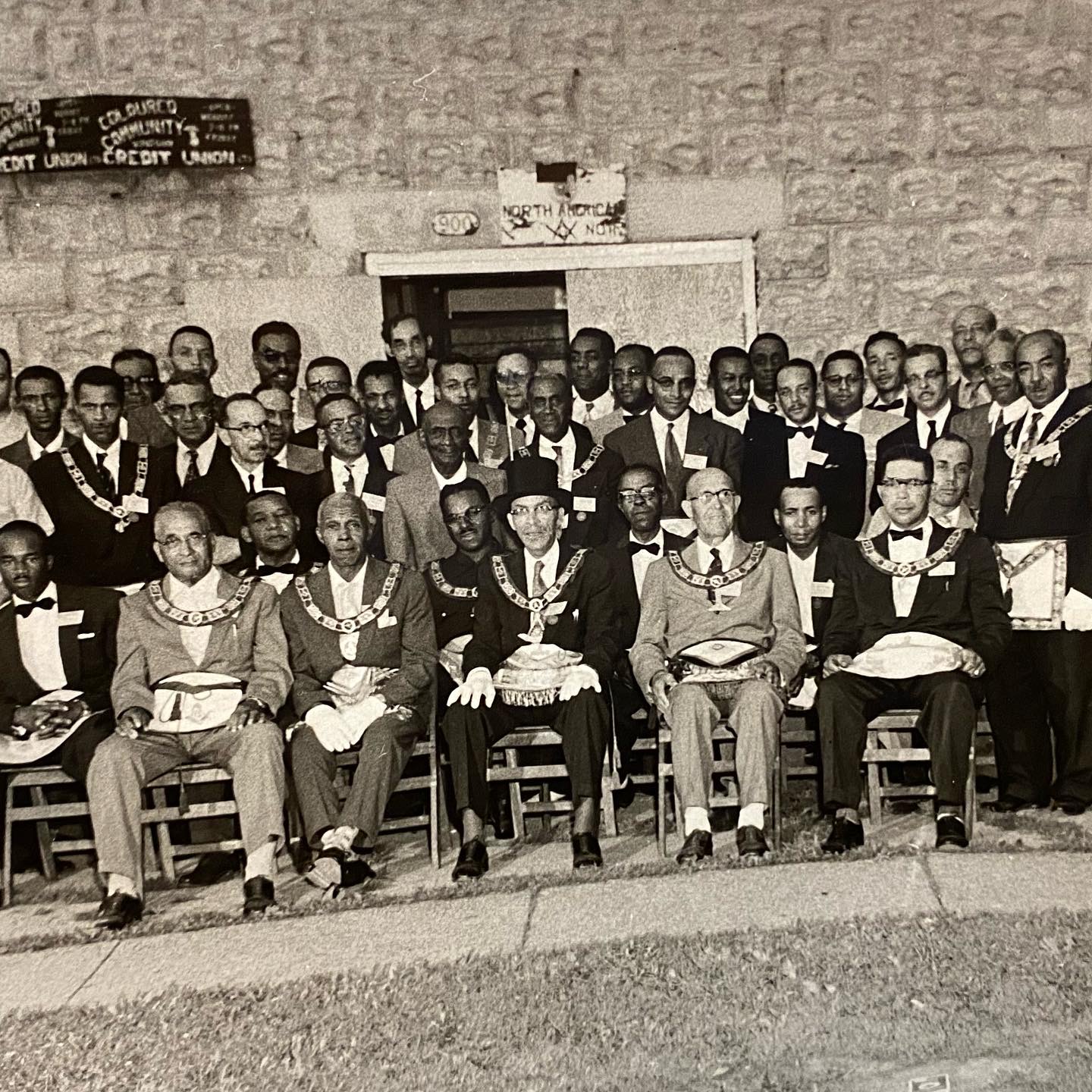

McDougall Street was also home to Landrum Hall, the most popular social hall in the Corridor. In the late 1920s, John Landrum (who often went by the name Ellis Scrivner), a Black Mason and prominent landowner, purchased a plot at 452-454 McDougall Street and obtained a permit to build a two-story, five room public hall. Initially, the hall served as a meeting place for Windsor’s Prince Hall Freemasons. Later, other Black organisations rented the hall for social events and club meetings.

The Black community was a significant demographic within the third ward and from the 1920s to the 1950s, municipal candidates often held rallies and public forums at Landrum Hall hoping to acquire votes from Corridor residents.

The hall was rented in the 1930s by Clarence Monroe, who began operating his Frontier Social Club in the building. The Club served as one of Windsor’s most popular Black spaces, not only for music and dancing, but for community fundraisers and political events. The Windsor City Directory of 1934 advertised the Frontier Social Club and much of McDougall Street as Windsor’s “Little Harlem.” During the redevelopment era, the Frontier Social Club moved to Brant Street and the original Landrum Hall building was expropriated in 1961 for the purposes of public housing.

A neighbour of John Landrum’s, Solomon Carter, established his own business not far from Landrum Hall. In 1913, Carter purchased a plot at 785 McDougall Street and later established a “coloured” restaurant between Elliot Street and Erie Street East. As detailed by elder and renowned cook, Mrs. Ella White, Carter’s restaurant catered to Black factory workers across the street. White worked for Carter as a full time cook for a number of years starting in the 1920s. In 1922, Solomon Cook relocated his restaurant to 245-249 McDougall Street, a location in the heart of the commercial district which would later become the location of Big Bear Supermarkets. In 1931, Carter’s restaurant moved again, further south to 341 McDougall Street.

Small Businesses and Shophouses

By the end of the nineteenth century, Edward Walker, owner of the Walker House Hotel, owned a number of plots along McDougall Street. At the corner of McDougall and Assumption Streets, and essentially in the front yard of a house at 365 McDougall Street, Mr. Walker built and operated a small meat shop and ice cream parlour with his son William. Front yard businesses, also known as shophouses, like the Walkers’ could be found in many neighbourhoods across North America in the early twentieth century due to their convenience and affordability within residential areas.

Just south of the Walker Meat and Ice Cream Shop was another shophouse owned by the Lawson family. Edward Lawson and his wife Wilhelmina Baptiste purchased their home at 71 McDougall Street from Hiram Walker (no relation) in 1883, later partially converting the house into a grocery store which operated well into the 1920s. Their daughter, Sarah Lawson Roberts, later opened her own beauty shop on Wyandotte Street, which she managed until her passing in 1942.

For men, small businesses included carpentry, electrical repair, mechanical work, and travelling barbers. There were a number of barbershops throughout the Corridor including those owned by Joseph Browning on Wyandotte Street East, Freeman Dungy on Mercer Street, and Arlington Dungy on Howard Avenue. A number of men also found employment as barbers at a few downtown hotels, including the Prince Edward.

Harding Electric was a family-run business with its office initially located in the home of the Harding Family. Morris Harding was a master electrician who, alongside his wife Ruth, operated this successful business for more than forty years beginning in 1947. The family operated out of a home at 1136 Windsor Avenue and another in Sandwich West.

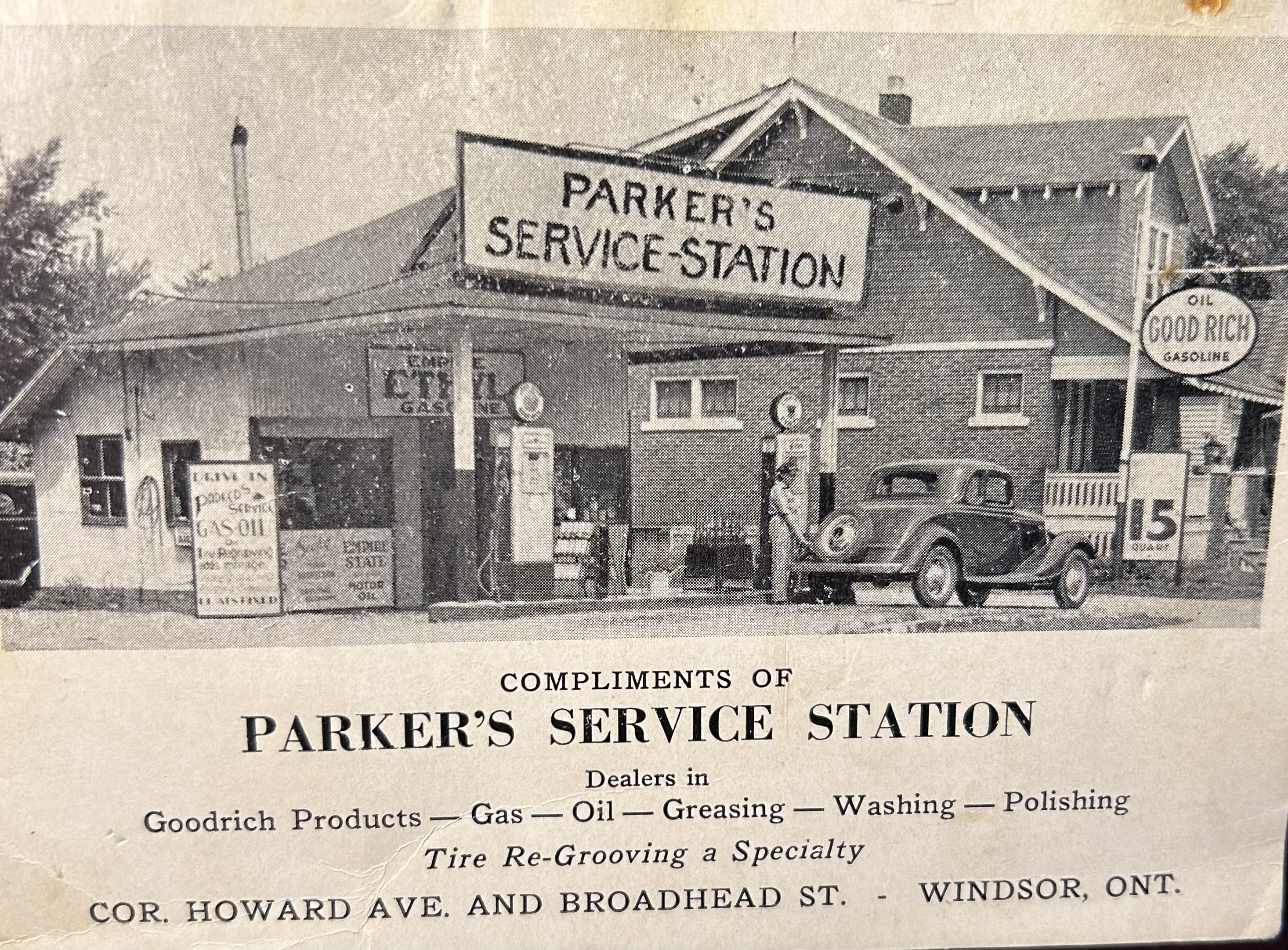

Emmanuel C. Parker and his family ran a confectionary store out of their home at 840 Mercer Street. It was a popular establishment especially with students across the street at the Mercer Street School. Emmanuel’s son Alton Parker, the first uniformed Black police officer in Windsor, also owned Parker’s Service Station at the corner of Brodhead Street and Howard Avenue where he worked as a mechanic before joining the Windsor Police Service. Alton Parker also owned a number of small apartment buildings in the community which he routinely rented to Black families.

Women’s Businesses in the McDougall Street Corridor

Earlier in the twentieth century, employment prospects for Black women in Windsor were especially bleak. Some women were able to find work as nurses, educators, or even shop owners, and others travelled to Detroit as domestics. Most assumed the responsibilities of family life and turned to informal methods of employment that could be done within the home.

Interviews conducted for the We Were Here project revealed that the Black women in Corridor made additional income through laundry, tailoring, and hairdressing operations they ran out of their homes. One interviewee recalled a woman who made and fixed curtains. Another recalled a call-to-order meal service in which residents would call the home of one community member and place an order for a home-cooked meal for pick-up.

Catherine Madeline Sobrian operated a vocal studio from her home at 1034 Highland Avenue beginning in 1924. According to the Dawn of Tomorrow, she was “the only representative of our race” to teach Black students in this vocation and was trained in Chicago.

Sadie Johnson’s Blue Tea Room restaurant, located in her quaint cottage home at 871 McDougall Street, promised fried chicken dinners and Canadian barbeque. Johnson also provided catering services to Windsor and Detroit residents as advertised in a number of print ads in the Detroit Tribune during the 1940s.

Laura Chase Perry, the mother of Dr. Roy Perry and Walter Perry, operated a small restaurant on the front porch of her home at 789 Mercer Street. Turning the porch into something akin to a sunroom, Laura named her restaurant the Verandah Inn, serving customers who “started to come regularly from downtown Windsor and Detroit” for her excellent home cooked meals.

The lack of formal documentation of these informal, female-run businesses has resulted in the relative invisibility of the services available within the community. Oral histories have made it possible to preserve some of this unique economic history and more fully document women’s contributions to the neighbourhood.

Banking in the McDougall Street Corridor

Credit unions were valuable institutions during the twentieth century as it was incredibly difficult for Black families to secure mortgages or other loans from traditional banks due to negative perceptions of Black people. Black credit unions ensured that families could purchase homes, establish businesses, or secure personal loans.

Thus, an essential business within the Corridor was the Fellowship of Coloured Churches Credit Union. Founded in 1944, the Coloured Credit Union was dedicated to creating and preserving Black wealth in the community. Initial meetings were held at 480 Brodhead Street, the home of civil rights activist Hugh Burnett, who served on the committee for several years. The Credit Union later rented a space in the North American Masonic Lodge Hall at 900 Mercer Street.

The Coloured Credit Union created a student aid bursary which provided Black students with much-needed funding to pursue post-secondary education. The organisation later changed its name to East Side Windsor Credit Union Ltd. and purchased a larger building on Erie Street once their membership grew past two-hundred and fifty. The Credit Union continued to serve the community into the 1980s. When traditional banks began lifting their discriminatory policies, interest in this neighbourhood credit union slowed.

Medical and Other Professionals in the McDougall Street Corridor

Those with specialised training or post-secondary education occasionally assumed roles that were otherwise unavailable to most working residents of the Corridor. Lyle Browning, for example, started his career in automotive manufacturing and would eventually become president of the Car Steel Corporation of Canada, Ltd. in 1953. Browning was the first Black Canadian to be appointed president of a major auto-parts manufacturer. He would later go on to establish J. L. Browning and Co. and Browning Engineering and Manufacturing Co. in 1972.

Black medical professionals rented offices for their respective practices in the Corridor to address the health needs of residents. One such location was the joint offices of Dr. Roy Perry (Dentist) and Dr. H. D. Taylor (physician) at 460 Wyandotte Street. From 1942 to 1958, these men provided an essential service to the community as many people have shared that they felt safe receiving medical care from people they knew and trusted. Many residents did not feel that same sense of security visiting doctors or hospitals outside of their community. Unfortunately, this office was expropriated in the late 1950s as part of the urban renewal program. Dr. Perry later re-opened his dental practice on Goyeau Street in 1958, where it remained until his passing in 1972.

Other notable McDougall Street Corridor medical professionals included Dr. William C. Kelly, Windsor’s first Black dentist; Dr. William Kenneth Rock (physician); Dr. Othello P. Chatters (physician); and Dr. Louis Milburn (psychologist). Most of Windsor’s Black doctors were located along Wyandotte Street East prior to the redevelopment.

Employment Opportunities Outside the McDougall Street Corridor

Though the McDougall Street Corridor boasted many independent businesses, most Black men and women had to secure employment outside of their community. Ford Canada was one of the largest employers of Black labour in the city, though they initially hired limited numbers of men from the Corridor. Black men were often restricted to foundry work, which was arduous and low paying.

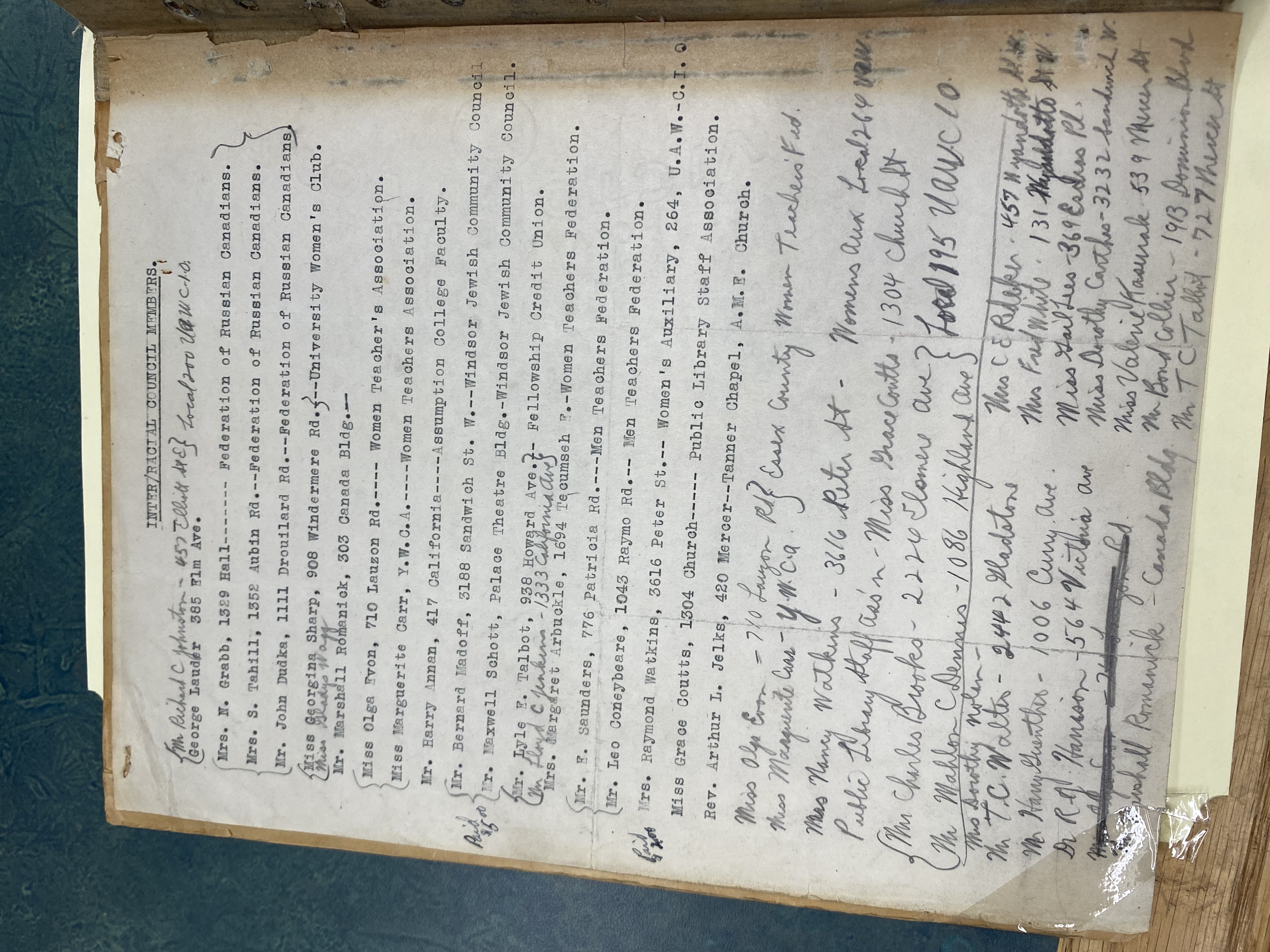

In 1949, the Windsor Interracial Council produced a community audit report that observed racial discrimination in various sectors of the city. The report found that few employers in Windsor hired non-white workers. In fact, those companies and businesses that did hire visible minorities often concentrated them in low-paying, laborious positions. Black men were concentrated mainly in automotive industries and small service industries, with the majority of these men employed at only a handful of companies.

A questionnaire distributed to local factories demonstrated that 97.8% of employable Black men were in common labour positions, even though approximately 10% of these men had the skills necessary to assume “better jobs” within these respective factories.

Similar statistics showed that 90% of Black employees of the City of Windsor held common labour positions as well. These disparities were improved slightly by the passing of the Fair Employment Practices Act in 1951. But for many, positions in offices or skilled trades would be unattainable for another decade.

By mid-century, Black women were beginning to assume more visible roles in the work force. Still relegated to certain fields and lower paying positions, Black women nevertheless excelled and pushed through the boundaries that were placed before them, assuming positions as secretaries, clerks, comptrollers, nurses, and educators across the city.

Many McDougall Street Corridor residents found success across the river, with some applying for positions with Black employers. Cecil Craven, Lavina “Tiny” Robbins, Duchess Johnson, Mary Stewart and Arytia Chase all wrote for the Windsor Spotlight column in the Detroit Tribune at various points between 1933 to 1945. For more than a decade these ladies contributed to this column, keeping family and friends in Detroit up to date with the news of the McDougall Street Corridor.

Survey data collected in 1958 on shopping habits in the redevelopment zone revealed that residents conducted more than 70% of their shopping at neighbourhood grocery stores and specialty shops. Additional shopping was done at the Windsor Market and nearby stores along Ouellette and Wyandotte Streets.

While the survey does not indicate how many respondents were Black, the pattern suggests that residents of the downtown core tended to shop within a limited radius from their homes. This finding is bolstered by the fact that only 30% of the respondents reported owning a vehicle. The numerous and varied businesses in the McDougall Street Corridor suggest the needs of community were often met through the formal and informal services of other residents.