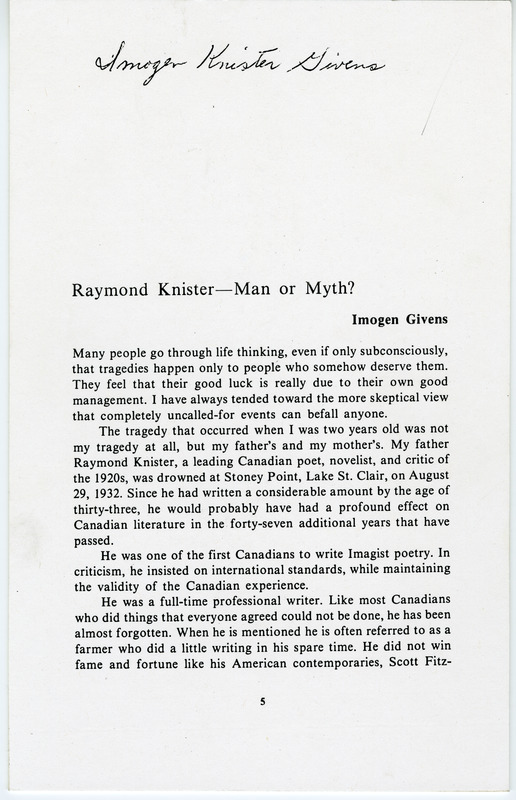

Raymond Knister—Man or Myth?

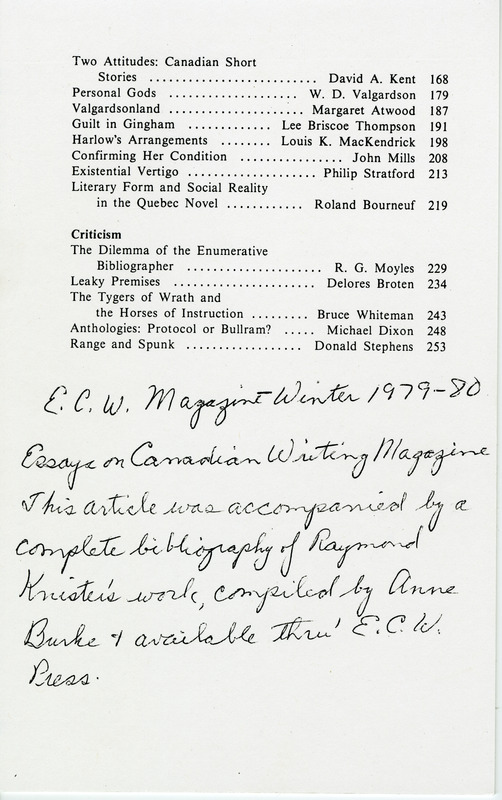

By Imogen Knister Givens, originally published in Essays on Canadian Writing Magazine, Winter 1979-80. The essay includes a diary excerpt from Myrtle Knister, Raymond's wife, recorded the summer of his death.

Many people go through life thinking, even if only subconsciously, that tragedies happen only to people who somehow deserve them. They feel that their good luck is really due to their own good management. I have always tended toward the more skeptical view that completely uncalled-for events can befall anyone.

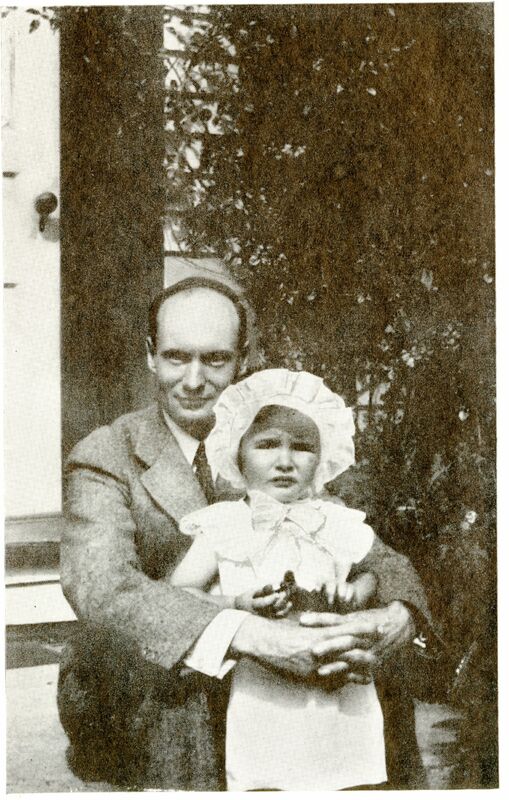

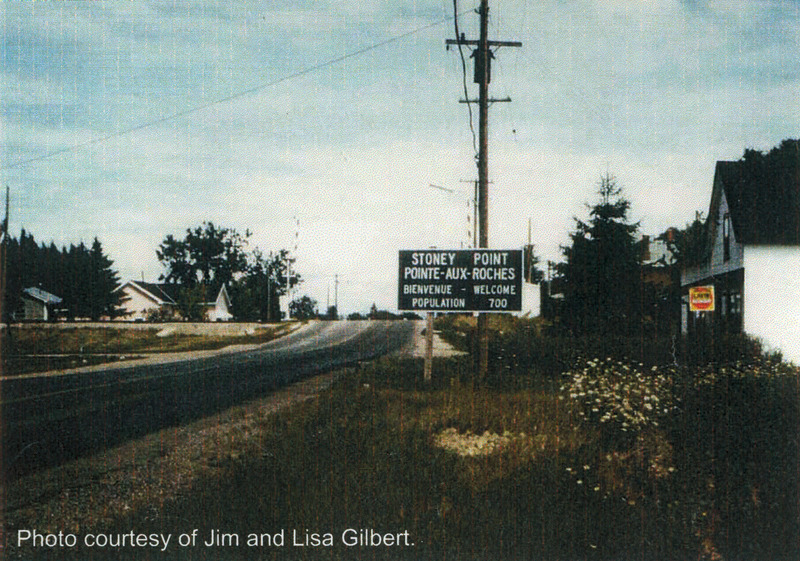

The tragedy that occurred when I was two years old was not my tragedy at all, but my father's and my mother's. My father Raymond Knister, a leading Canadian poet, novelist, and critic of the 1920s, was drowned at Stoney Point, Lake St. Clair, on August 29, 1932. Since he had written a considerable amount by the age of thirty-three, he would probably have had a profound effect on Canadian literature in the forty-seven additional years that have passed.

He was one of the first Canadians to write Imagist poetry. In criticism, he insisted on international standards, while maintaining the validity of the Canadian experience.

He was a full-time professional writer. Like most Canadians who did things that everyone agreed could not be done, he has been almost forgotten. When he is mentioned he is often referred to as a farmer who did a little writing in his spare time. He did not win fame and fortune like his American contemporaries, Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway, but he was able to write full-time, which was all he really wanted. In the eleven years from his first short story in 1921 until his death in 1932, he wrote three novels set in Ontario, a non-fiction novel based on the life of John Keats, about one hundred short stories, an equal number of poems, and a play. He also wrote hundreds of book reviews for magazines and newspapers in the United States and Canada, and articles ranging from humorous essays for The Star Weekly and stories about Long Point and Point Pelee to lengthy critical studies of the leading writers of the time. He also edited the first anthology of Canadian short stories in 1928, the only one until 1947.

However in the communities where I have lived, in small-town and rural Ontario, most of the people, like Canadians anywhere, could not name half-a-dozen Canadian writers. They have little interest in literature, Canadian in particular. Therefore I never considered myself the daughter of a famous person, nor did I have the contact with the literary world that might have occurred if my father had lived. Nevertheless I was curious to know what sort of person he had been and what he had been trying to do in his work. It has proven to be a fascinating search.

Since I was only two years old when my father drowned, I did not have the usual feelings of affection, anger, and guilt that are common in parent-child relationships. I did have a trunk full of his letters, manuscripts, and note-books. My mother remarried and had four more children to raise, so when I married I took my father's books and papers with me. Until the last few years I have been too busy with my family of three daughters and three sons to do much traveling to talk to writers who knew my father. I have talked to a few but their memories are rather vague after forty years. My relatives remembered what sort of person he was but knew little about his work. My mother, of course, knew him best and he always involved her in the work he was doing. She remembers the poems he loved to recite and the books he was most enthusiastic about, and has many memories of the literary community in Toronto in the 1920s. The old copies of This Quarter, The Midland, Dial, Maclean's, books received for review, news paper clippings, correspondence and an old ledger with jottings of money spent, short stories written, rewritten, sent out, accepted or rejected, and ideas for stories never written, all add up to a fairly complete picture of his life.

John Raymond Knister was born on May 27, 1899, at Ruthven Ruscomb [edit by Knister Givens], near Windsor, Ontario. His great-grandfather had come from Germany after the Napoleonic Wars. (The name Knister is pronounced with the "K" sounded and the "i" long.) The Knister farm was on the north shore of Lake Erie, like the one where John Kenneth Galbraith was born nine years later. Robert Knister, his father, [edit by Knister Givens] grew seed corn and soya-beans and raised pedigreed Clydesdale horses. His wife, Raymond’s mother, [edit by Knister Givens] the former Elizabeth Banks, was of Scottish descent and had been a teacher.

Raymond decided to become a writer and prepared himself by reading the classics of world literature, some in the original Latin, German, and French. The old ledger still exists in which he listed "Books Read" from the age of fifteen to twenty-five, about eleven hundred in all, ranging from the classics to the newest experimental writers. In 1919 he enrolled in Victoria College, University of Toronto, but in February contracted pneumonia in the devastating influenza epidemic. When he recovered he continued writing and studying on his own, as well as working on the farm. He had been writing poetry and had contributed essays to the Victoria College Magazine, Acta Victoriana. During the winters of 1921 and 1922 he wrote the stories that are in so many Canadian anthologies—“The One Thing," “The Strawstack," "Mist-Green Oats," "The Loading," and "The Fate of Mrs. Lucier." An American literary magazine, The Midland, published "The Loading," "Mist-Green Oats," and seven of his poems in 1922. He was also writing a book-review page for the Windsor newspaper, and doing free-lance journalism for the magazines.

In 1923 he went to Iowa for a year to act as Associate Editor of The Midland and in the summer of 1924 spent some time in Chicago, writing by day and driving taxi by night. When his taxi was commandeered by some criminals, he was temporarily thrown in jail along with them, giving him the material for the stories, "Innocent Man" and "Hackman's Night." He had to return to Canada to help his father move to a new farm.

During the 1920s his stories were placed high on O'Brien's Honour Rolls of The Best Short Stories of each year. This Quarter, a literary magazine in Paris, which published newer writers such as James Joyce, Carl Sandburg, Ernest Hemingway, and Morley Callaghan, published two Knister stories, "The Fate of Mrs. Lucier" and "Elaine," and twelve of his poems. In 1925 he was supporting himself by writing a weekly sketch for The Star Weekly while continuing to work on his novels. In 1926 he became engaged to Marion Font, daughter of a wealthy New Orleans family, whom he had met while attending the University of Iowa. The romance started well, with both sets of parents disapproving because the Fonts were Roman Catholics and the Knisters were originally Congregationalists, by this time United Church. Later Marion started issuing orders, one being that he give up writing for a more profitable occupation. Meanwhile he had moved to Toronto and had fallen in love with Myrtle Gamble. They were introduced by a mutual friend, the poet Wilson MacDonald, and were married on June 18, 1927. She had studied at the Ontario College of Art—Arthur Lismer was one of her teachers—and she kept her job as a dress designer after they were married. That summer he wrote White Narcissus which was published in 1929 in Canada, Britain, and the United States. Canadian Short Stories, published in August 1928, took about a year to compile.

Canada almost had a volume of Imagist poetry in 1926 as Lorne Pierce of Ryersons offered to bring out his poetry. But first the manuscript was cut by twenty poems to chapbook size, then Pierce suggested that the author subsidize the printing costs. Windfalls for Cider finally appeared in 1949.

After three years in Toronto, the Knisters moved to a farmhouse near Port Dover, where he researched and wrote My Star Predominant, based on the life of John Keats. In March 1931 the Graphic Press awarded him first prize of twenty-five hundred dollars for the book. That summer they moved to Montreal, traveled to Quebec City, and then rented a large house at Ste. Anne de Bellevue for a year. During 1931 he had many stories and articles printed in the magazines, but in May 1932 the Graphic Press declared bankruptcy. He had received over half the prize-money but the book had not been published. In June they traveled to Ontario and Lorne Pierce managed to get the rights to the book from Graphic and promised my father a part-time editorial position with Ryersons.

My mother kept a diary and in it she recorded the events of that summer from the time they arrived at Port Dover to visit her parents.

(Excerpt from Diary)

We reached Port Dover about seven o'clock and they were glad to see us and made a big fuss over Imogen. We stayed here for six weeks or so. Raymond went to Toronto a couple of times but we did not go. Finally he had arranged, with Professor Pelham Edgar's aid to occupy a cottage at Port Hope. So, as we had a couple more weeks before the cottage would be ready, I suggested we go to visit his sister Marjorie. We had been promising to go up all along. We went up in August and it was pretty·warm there and Imogen and Bobbie did not get along. On Sunday we went on a picnic to Belle Isle and the following Tuesday we drove out to Comber to see Uncle John Goatbe. He took us out to see a cottage he owned at Stoney Point. It was very attractive and Raymond was quite taken with it.

Partly because he was weary of visiting and partly because Imogen was exhausted from crying and not sleeping, we decided to take the cottage. He paid two weeks' rent and we went back to Windsor and told Marjorie. We bought groceries and left next day. My sister, Verna, was with us and she and Raymond took the boat out and went swimming after dinner. The shoreline was choked with weeds so that it was necessary to row out to deep water. Friday they went out again and Saturday Verna went home. Sunday, Marjorie, Clarence and Bobbie came and I watched the two children while the rest went swimming.

Monday we three went out in the boat but in Wednesday's paper was an account of a baby just Imogen's age falling out of a boat, which frightened me. On Thursday we waded out and got in the boat and when we got out about a mile he wanted to row still further and did in spite of my coaxing him not to. Then we rowed back and were in the same locality as he usually went swimming in. He touched bottom with the oar, played with the baby a minute and then let himself down over the prow of the boat. But he couldn't touch bottom so he pulled himself back into the boat. He put the oar down again and found he could not touch bottom with it. So we must have drifted over a hole in those few minutes. He went swimming further in to shore. I said to him, "Now Raymond what would you have done if you had let go of the boat? You would have gone right down to the bottom of that hole and from pure surprise you would have opened your mouth and taken in a lot of water."

He agreed that he might have but just laughed about it. That frightened me because I could see that if he disappeared beneath the water, the little girl would have had to be left in a floating boat if I went in after him.

He went alone the next couple of days and seemed to enjoy the water so much. He would come home looking tired and brown and stretch out on the sunny verandah to brown still more. He said it made him feel like a new man. There was a corn-field opposite and he would take Imogen and go over and steal some corn for dinner. She just loved carrying an ear home and then they would husk it together. One day when he was ready to come home, she wasn't and cried so loudly the neighbours must have heard. Raymond looked so comical coming out of the cornfield with ears of corn sticking out of his pockets and the little girl held wriggling and howling under one arm. Then he would tie a rope to the dust-pan and put the teddy-bears on it and run around the room for her to see how long they would stay on. He made a sort of walk of blocks for her to walk up and across. Raymond would carry her little parasol and show her how to imitate a tight-rope walker.

The second Sunday Ray's cousin Lorne Knister and a friend came to visit. After supper we sat around talking, and invited them to visit us at Port Hope. I promised them a spiced-ham dinner which was Raymond's favorite' meal.

The next morning I started packing and got ready to leave, all but the mopping. Raymond would have liked to stay longer but we could not spare the time or the money. It began to rain and kept it up until after noon. Uncle John came and Raymond went with him to fix the water system, which had broken, and stood talking with him until nearly noon. I got all the papers ready to burn and told him to light the fireplace but to look up it first and see if the draft was open. He, boyishly eager to light the fire, touched a match to it first and then tried putting his head up afterward. I came into the room just as he was drawing back nearly scorched. I scolded and spanked [edited by Knister Givens] him for putting himself in danger.

After lunch we put Imogen to bed for her nap and he began reading poetry aloud while I mopped the floor. Soon he began talking about Keats and as I saw it was going to be a long talk I put the mop in his hand and flung myself on the couch. He good-naturedly took the mop and kept right on with his soul-edifying talk about the immortals. After a lengthy discussion of Keats, he said, "I feel just like Keats did when he was just coming into his powers. I feel as though I am just coming into mine. The world is before us, Myrtle. We have everything we want and we are happy." And he talked cheerfully of all the things we would do when we got back to Toronto. He was going to work in the editorial room at Ryersons with Lorne Pierce. We were to stay in a cottage at Port Hope. I dreaded the thought of the long days alone there and happened to say that maybe Imogen and I could stay awhile at my mother's place until he saw if he liked it at Ryersons. But he was indignant at the very idea and said I didn't appreciate having a husband who was independent.

How very true have all his words proven since! I have written these words between heart-rending memories and tears. My poor little girl wonders why her mother doesn't sing and dance anymore and sometimes scolds her unjustly. If I am crying, she looks up at me and weeps too.

But, to continue the story, Raymond said, "Let's all go for one last swim," and wanted me to get Imogen up from her nap. But I said, "No, she is safe in bed and will stay there." He coaxed and I said maybe I'd go fishing if I could find some fish-worms. So we poured pails of water on some soft ground at the back of the house and dug into it with sticks, but never a worm came up. So I said that settled it, as though I had flipped a coin. He said he would go over into the bush and get a green frog he saw that morning for bait. But I knew he wouldn't as he was very kind to animals and creatures of all kinds. So he stood around, and I could have told him not to bother going as it was almost four o'clock. But I said, "Well, if you are going you may as well go as I am not coming."

He said, "Well, I think you're a pretty poor sport."

I said, "I know I am, but I've had a lump in my throat ever since we came to this place and I’ll be glad when we leave."

He said, "Well, we won't have this lake next week!"

So he put on his suit and said as he was going out the door. "Well I get tired of going alone!"

Poor dear! And I let him go at that. He walked slowly down the road and over the beach and I watched every step he took and wished I had told him to wait and we would have gone along. So I went straight into the bedroom and Imogen was awake and I put her sun-suit on her and got into my bathing-suit and after locking the house went down to the beach. But Imogen walked so slowly that by the time we got there he was out a mile, swimming back and forth to his boat. There were some fishermen putting out in a boat but there were no other boats or swimmers in the lake. I waved my red jacket at him as I saw him swimming towards his boat again, but do not know whether he ever saw it or not. Then I thought with a panic that he was almost in the identical spot where we found the hole last week and then another thought from nowhere—”Oh, he's too lucky! Nothing would ever happen to him!"

Just then a little French-speaking girl started to pull Imogen's parasol away from her and I turned to separate them. Then I got my sketching book ready and began to draw a few lines for a boat. Then I looked out and could not see him swimming but saw the boat had drifted somewhat with a little breeze that had sprung up. I put down the sketch-books and red coat on a stone. I carried Imogen out to a large rock and set her to playing there. I stood up on top of the rock and waved and screamed to Raymond, but I could only see the boat floating empty. I gathered Imogen up in my arms and ran as fast as I could over to where two small boys were putting out in an old rowboat. I called to them to go out and see if there was a man lying in that boat. Then I carried Imogen up a steep bank to try to get help from the men who had been on the beach. Just as I rounded the corner of the cottage I saw the men going away in a car. Before I could get a word out, I was so spent from carrying the little girl, they had gone.

I left Imogen with a French-speaking woman, hoping she understood, and ran back down to the water again. I ran, calling at every step, as I now saw the boat was drifting away at a great speed. It was as far again by now as it was when the boys were setting out. I never stopped running and calling until I was as far out as l could wade. By now the boys were altering their course and had gone over to where two men were fishing out of a boat, to ask them to help. But they said that the boat was empty when they saw it first and that the only way that they could help would be if the boys would go back in to shore and up to their cottage and get their outboard motor. I was about exhausted by now and screamed for the boys to come back and get me. They came for me and wanted to go in after the motor, but I was fascinated by the horror of that fast disappearing boat, bobbing up and down like a cork on the waves. He might easily be hanging on to it, too weak to pull himself up into it, and our delay might mean that he would just slip off before we got there. So we pulled that old tub of a boat for about three-quarters of an hour and as we gained on the other boat we all three thought we saw a head and shoulders over the prow of it. Oh! the suspense of that last pull and the awfulness of that bathrobe rolled up boyishly in the prow of that boat . . . and nothing else . . . can hardly be dwelt on!

So we started back over the route we had come and I was nearly crazy with grief by this time. As we seemed to be over the area where he had been swimming I tried to get out of the boat, but the boys rowed faster than ever and I guess I would only have drowned.

This had happened about 4:30 or 4:45 and we got in off the lake at nearly 7 o'clock. In that time not a boat or swimmer had put out to aid us although quite a crowd had collected on the beach. The two fishermen actually shouted across to us on our way in and would not believe there was anyone drowned and said he had just played a trick on me and was probably home at the cottage, waiting for me. I was so angry, and so grief-stricken that I called them down for fair. Even then, they drove on ahead of me in their car to the cottage, while I trudged along carrying Imogen until some bathers ran along and helped me. I unlocked the cottage and of course there was no one there. His typewriter was on the table, and his clothes were lying on the bedroom floor, just as he had stepped out of them to put on his bathing-suit.

In spite of the awful truth which was forced on me, I could not believe my Raymond was dead. I began calling Uncle John Goatbe on the phone and his son Carl came right out with the truck and went down to the lake to see what he could do. Imogen and I were all alone in the cottage and I cried so hard, she thought I was laughing and lay on the floor and kicked and laughed. She asked when her Daddy was coming to give her a boat-ride.

They did not find him for three days, in spite of boats and planes and divers. My father and brother came with equipment from their shipyard to direct the search. Finally the divers with grappling hooks found Raymond's body wedged in a hole in the bottom of the lake, held down by the strong undertow.

Epilogue

In the 1940s Lorne Pierce decided to bring out my father's poetry and asked Dorothy Livesay to write a "Memoir." Since this was, for many years, the only biography, everyone refers to it for information. Unfortunately, Livesay chose to distort both his life and his death. She says in her book, Right Hand, Left Hand, that she "began collecting his poems." Actually she simply used the shortened manuscript Pierce had, leaving half the poetry unpublished, but leaving ample space for her own writing.

Livesay was only twenty-two when my father died and, by her own account in Right Hand, Left Hand, had been in Paris for a year living with a man named "Tony." She saw my father once in the summer before he was drowned. He was a friend of her parents, particularly her mother who had been editing an anthology in which some Knister work was to be included. Yet in Right Hand, Left Hand she says, "I thought immediately that I was the cause of his death" (p. 48). She gives no reason for this. A highly intelligent man with a career planned is hardly likely to commit suicide over a casual acquaintance who is caught up in Marxism and "free love." However, Dorothy Livesay seems to be a person who sincerely believes whatever she wishes to believe, in spite of all evidence to the contrary.

Many anthologies record that Raymond Knister drowned at Port Dover, because Livesay says, "the funeral which took place near the scene of the drowning in Port Dover."1 Port Dover is at the eastern end of Lake Erie, thirty-seven miles from Hamilton, a long way from Stoney Point, Lake St. Clair. Yet she claims to know the very mood he was in the day he drowned. Livesay gives her version of Mother's diary, which I have just quoted, but she changes it to conform to her theory, as a comparison will show.

My mother and her sister Minnie, a close confidant of my father because she was interested in writing too, both recall that my father did not really approve of Dorothy Livesay. He referred to her as a "bluestocking" and thought she was a worry to her parents, especially her mother. Of course, she was ten years younger than them and so she was just a schoolgirl during most of the time she knew my father. Mother recalls that my father had an instinctive distrust of women who wanted to tell him what to do. His mother was very manipulative. So was Marion Font, his fellow psychology student at the University of Iowa, who, like Livesay, became a Social Worker; Marion was the girl he decided not to marry. I have all her letters, and some of his to her, as he kept carbons of most letters he wrote, even love-letters. Both his parents were very strong-willed people, his father a typical German patriarch, very warm and hospitable, but very domineering; his mother was a Scottish school-marm, very reserved, and not about to be dominated by anyone. Although they had produced a son who was very generously endowed with will-power, they had also produced a marriage that was a prolonged "cold war." Since my father could not change his own personality, he very wisely chose a wife who was good-natured, adaptable, and happy-go-lucky. She came from a large, happy family, Irish and English on her father's side, Irish and Pennsylvania Dutch on her mother's. She was charmed by his habit of quoting poetry and by his outrageous sense of humour. His stammer was like a barometer; with compatible people such as my mother and her sisters, and certain male fellow writers, it practically disappeared. His mother and Marion Font both had the opposite effect. He seems to have aroused the social worker in Dorothy Livesay as well. In life, he resisted her. After his death, she was able to put him in his place.

It is not surprising that Livesay did not understand my father since his way of thinking was quite the opposite of hers. He was a skeptic—about religion and about political ideologies. He concurred with Keats's belief in the negative capability. He felt that the only hope people have of arriving at the truth is to abandon the habit of twisting facts to fit some preconceived system. Because he disagreed with her and said she was wasting her talent by writing political material when she could be writing lyric poetry, she said that he "had gone a long way down a dark road. He had lost somewhere his sense of direction." She claims, "He had talked to religious men, seeking a way to calm himself."2 If she had known him as well as she claims, she would have known he was an agnostic. He had to see an Anglican clergyman on that trip to Toronto, but it was about an assignment to write a history of the Masonic Order. She disapproved of my father's desire to live like Thoreau and claimed that proved he was an "escapist." My mother had been very happy living by the lakeshore while the Keats book was written.

In order to support her suicide theory Livesay had to prove that Knister failed to earn a living. She says, "Knister was not the type of man to cope with a bankrupt press."3 He was a poor choice to portray as a martyr as he was one of the few Canadians of his generation who did earn a modest living by writing. He did a great deal of journalism, as well as having a rather surprising literary success by the age of thirty-three. In Right Hand, Left Hand she says, "Wilfred Eggleston has told me that he happened to be living in an apartment m Toronto’s Parkdale, below the Knisters and knew that they were visited by the bailiff for non-payment of rent. They had to move. By the time I met Raymond again he had moved many times and was living in a cottage at Port Dover."4 Mother remembers the Egglestons quite well. Both couples were newly married, and since Mother loved to cook, the Egglestons often ate with the Knisters. The sheriff probably came about the rent from the previous apartment. My father was very punctilious about paying his just debts, but was constantly breaking the leases on apartments and then would pay only for the length of time he had actually occupied them. He tells about this in his letters as well as in his story “A Brush With Quebec Law" printed in Raymond Knister: Poems, Stories and Essays. He was most contented renting a whole house in the country and running the furnace himself. In city apartments he was always encountering annoyances. Because he worked at home he was very conscious of lack of heat or noisy neighbours who interfered with his concentration. He also loved arguing with landlords, or anyone else, when he was sure he was in the right. So they moved often, in the city, but never in order to cheat anyone on the rent.

When the "Memoir" was condensed for inclusion in Right Hand, Left Hand, Livesay's errors were compounded. The latest version states that the Graphic prize was one thousand dollars of which Knister received seven hundred, most of which went for legal fees. The prize was twenty-five hundred dollars, of which he collected over half. a considerable amount of money in 1931, when wages were a dollar a day or less. Compared to the very real suffering that other people had to bear in the Depression, the Knisters considered themselves fairly lucky. They had no debts and owned a good car, new furniture, good clothes. and a large collection of valuable books, some of which I still have. Best of all, my father had a compatible job waiting for him. Mother's father, George Gamble, owned a shipyard and would have helped them if it had been necessary.

Of course Livesay's version makes a better story. Someone has said that it is no longer enough for a poet to be dead before he can be famous—he must be the author of his own demise. And we all know that a Canadian has to be a loser.

I was just a schoolgirl when the memoir came out and my mother hesitates to enter into conflict with a famous person like Dorothy Livesay who has the media at her disposal. Mother told the truth to anyone who interviewed her, but most preferred Livesay's story.

In 1973, Marcus Waddington came to talk to Mother because he was basing his Master's Thesis on Knister. We suggested he take Livesay's "Memoir" with a grain of salt, but at that time he was sure her portrait must be accurate.

I wrote to Miss Livesay to find out her reasoning, as I had always admired her poetry and did not want to misjudge her. Her appreciation of my father's work was excellent. It was only when she tried to interpret his personality and mental processes that the distortion occurred. Her interpretation was tentative at the time, but other people's enthusiastic acceptance of it created the myth of what she calls his "self-immolation to save the world."5

Livesay replied that she was not implying suicide but that the marriage was breaking up. She sent a copy of a letter that she said proved she was right. It was from Elizabeth Frankfurth, a spinster friend of my father, whom my parents had visited a few days before the drowning. The letter begins, "No, Miss Livesay, I do not think Raymond Knister was emotionally insecure," and goes on to say she does not believe he committed suicide. Later in the letter she says, "I do not think his wife is capable of understanding his stories"—a common reaction of female friends to authors' wives. Livesay also told me, in her letter, that while "Lorne Pierce was two-faced, R. K. was multi-faceted." She said, "I am not speaking of the possible suicide of Raymond. That is of the smallest significance." In one of her letters in Right Hand, Left Hand, she says, "Is the reality more important than the imagined? Does it last longer really?" The effect of her strange "Memoir" on Knister's place in Canadian literary history seems to prove that point. Knister produced some of the most virile and sophisticated poetry, prose, and criticism of his time, but her stereotyped picture of him as a mentally ill "farm-boy" has killed interest in his work. Perhaps this is not what she intended but this is the impression that has been conveyed, and no one ever questioned it, up to that time.

Marcus Waddington read all the published and unpublished work and all the correspondence, a lengthy task as my father saved all incoming letters and made carbons of those he wrote. He also read the notebook, the diary, and the news clippings of the time—interviews and news of the drowning, and reviews of my father's books in Canada and abroad. This was the same material that, Mother had supplied to Livesay. Waddington talked to her, and to her sister, Verna Gamble. In the end it became quite clear to Waddington that Raymond Knister had not been suffering from mental depression before his death and had not had creditors hounding him but had handled his business affairs with considerable acumen.

Waddington discerned a man with a sense of humour and a zest for life, coupled with unusual energy and self-discipline. Upon examining the outline for a planned novel, "Via Faust," and an article on Rilke, both of which Livesay used to develop her suicide theory, he found that she had misinterpreted these also. The Journal of Canadian Fiction's Knister Issue printed a condensed version of the biography Waddington wrote, in which he set forth his findings.

When Peter Stevens was working on his collection of my father's work, First Day of Spring, he wrote to McGraw-Hill Ryerson for permission to use the poetry as the book was out of print. They replied that they were about to re-issue it and that Mrs. Grace, my mother, had given permission. They had not even consulted her! We told them that we would like to see the book reprinted without Livesay's "Memoir" and with the rest of the poetry included. At first they agreed but later declined. The poetry remains unpublished. Livesay had the "Memoir" reprinted in her book, Right Hand, Left Hand, in 1977 although she knew how we felt about it.

I am not a very conventional person and I do not consider it a "sin" for someone to commit suicide or break up his or her marriage if it seems appropriate. These actions are not considered "scandalous" by this generation. I admire Dorothy Livesay for her feminism and her poetry. However I must object when the truth about a writer's life and personality is twisted in order to create a martyr or to prove a point in sociology. I'm completely certain that Raymond Knister did not die willingly. He had a tremendous love of life and a great many things he wanted to do. Also he was a very determined man and would have preferred to have had the last word.

Notes:

1Dorothy Livesay, "Raymond Knister: A Memoir," The Collected Poems of Raymond Knister, ed. Dorothy Livesay (Toronto: Ryerson, 1949), p. xxxvii.

2Livesay, p. xxxiv.

3Livesay, p. xxxiv.

4Dorothy Livesay, Right Hand, Left Hand, ed. David Arnason (Erin, Ont.: Press Porcépic, 1977), p. 48.

5Livesay, p. xxxix.

Handwritten note by Knister-Givens on table of contents:

E.C.W Magazine-Winter 1979-80. Essays on Canadian Writing Magazine. This article was accompanied by a complete bibliography of Raymond Knister’s work, compiled by Anne Burke + available thru’ E.C.W. Press.

Pages with annotations