Raymond Knister: An Appreciation

By John B. Lee

On Monday, August 29, 1932, thirty-three-year-old, award-winning southwestern Ontario author, Raymond Knister, full of promise, lost his strength and drowned in the slightly choppy waters of Lake St. Clair while swimming in the afternoon out beyond the weeds near Stoney Point. It had rained all morning the day of his drowning. Never a strong swimmer, he’d misjudged the lake and was sucked down by the undertow into a deep hole.

For three long days his body went unfound. Among the throngs of rescuers, his widow, Myrtle, searched for naught. As if to add to her distress, on Wednesday, a calm day of extreme heat, as she and her father and her thirteen-year-old brother, Harry Gamble, gazed over the wide blank surface of the still calm water, a total solar eclipse occurred adding a macabre livid blue mid-day darkness to her grief, followed briefly by weird crescent-shaped shadows created by a reappearing sun.

The following day, divers with grapples loosened the mortal remains, hooking the body from its deep hole so the apple-blight black and bloated corpse of the dead poet drifted slowly through the depths and eventually washed ashore from there, the face disfigured by fishes.

How horrible and morbid it must have been for the young wife as she was drawn away from the sight of her face-down husband into the consoling embrace of her grieving family. How great a sorrow to consider that two-year-old daughter Imogen would have no private memory of the man she called, “daddy.”

For some this tragedy became the myth of the poet drowned. But those who grieve a poet gone, might also think on father loss. For those who yet lament large silences of promise dying young, might also mourn the deeper loneliness of life destroyed and love distraught.

For there were those who loved and knew the man, who cherished the merit of what he had been, who grieved the life unlived and the promise unattained. That day remains for them the day a friend went down, the day a husband drowned, the day a father disappeared.

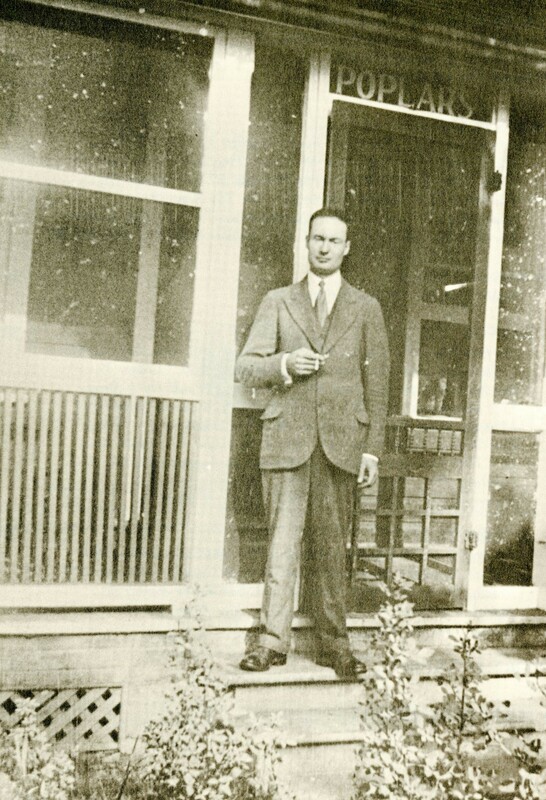

The remains of Raymond Knister had washed ashore and were found the morning of September 1st, the day after the sad and haunting eclipse. A large funeral, attended by dozens of writer friends of Knister’s acquaintance was held at Comber, near Stoney Point, the following day at 2 p.m. On September 3rd, at two o’clock in the afternoon of the day, a service was held in the residence of father-in-law George Gamble, in the village of Port Dover. That service was presided over by Knister’s friend and literary enthusiast, the Reverend David Cornish. Only a short while before, Cornish had accompanied Knister to the award ceremony where he was honoured for his prize-winning posthumously published novel. Knister’s body was interred at the Port Dover cemetery where his wife Myrtle lived after his death. Harry Gamble, the boy in the boat on the day of the fateful eclipse, lives there still.

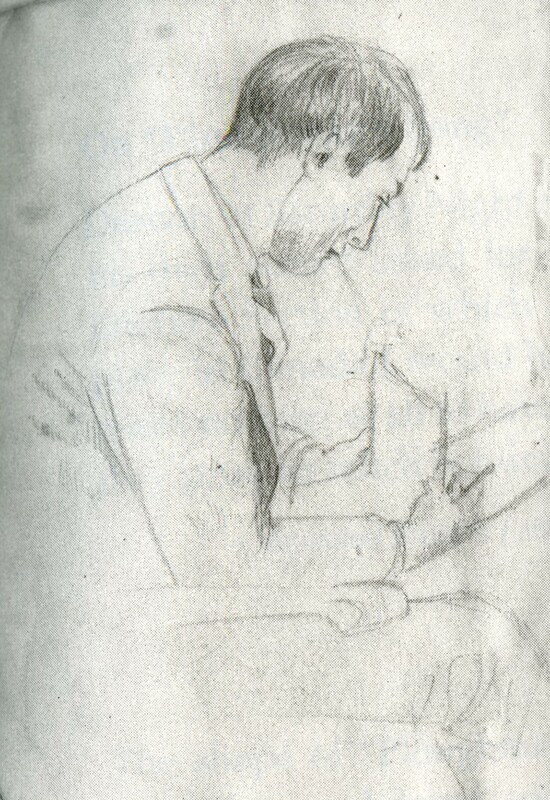

Born a farmer’s son, Raymond Knister was an avid and ambitious reader, setting himself the task of becoming a writer from a very early age. Unfortunately, his career as a student was cut short when he contracted influenza in the spring of his first year at the University of Toronto. His father brought him home to convalesce on the farm near Cedar Springs. Knister would stay there for the next two years to work the long hard eleven hour days, labouring through the summer in the fields and in the barns, and writing poems and stories in the winter months.