After Exile: On Raymond Knister

A collection of obituaries, letters of condolence and writings about Raymond Knister after his passing, originally published in After Exile edited by Gregory Betts (2003, page 105-122).

Border City Star, 30 August 1932

J. Raymond Knister Lost Life Monday Afternoon Whilst Swimming in Lake St. Clair at Stoney Point

Young Novelist Drops From Sight While Swimming.

Was Well-Known Short-Story Writer; Born in Kent County

Raymond Knister, of Toronto, was drowned late yesterday afternoon near Stoney Point while swimming about a mile off shore. The body has not yet been recovered.

Born in County

Born in Rochester township about 32 years ago, he was the son of the late Robert W. Knister and Mrs. Knister. His father was prominent in Agricultural circles in Western Ontario, and one of the active workers in the Com Growers Association for some years. The family home was in Essex County for some years and later in Kent County, south of Chatham.

For several weeks, Mr. and Mrs. Raymond Knister and their small daughter have been summering in the John Goatbe cottage at Willow Beach near Stoney Point. Yesterday afternoon he went out alone in a boat for a swim. He was about a mile off shore and in water about to his shoulders and Mrs. Knister was watching him from the beach when he jumped in for a swim. But he did not anchor the boat and it drifted away. In trying to swim after it, Mr. Knister perished.

Wife Alarmed

When Mr. Knister disappeared, his wife, frantic with fright, started to rush out into the water and then attracted attention of some fishermen nearby and they immediately went to the spot indicated by Mrs. Knister. They were unable to locate the body. The boat had drifted some distance out into the lake and was recovered four miles out.

He was known locally through publication of some of his works in The Border City Star.

He was one of Canada's most promising writers. A writer of short stories which are found in many modern collections, he edited a representative volume, "Canadian Short Stories."

Won $2,500 Prize Contest

He also wrote two novels, "White Narcissus" and "My Star Predominant," a novelized life of Keats; which won the $2,500 prize offered by an Ottawa publishing firm in 1931.

31 August 1932

To Mrs. Raymond Knister

Canada is greatly impoverished today. Her loss is the greatest since Carman left us. My deepest sympathies are with you Myrtle. Raymond was a loyal friend and the most brilliant son of soil of recent years. His spirit will live long among us.

Wilson MacDonald

Windermer, Ontario

30 August 1932

Raymond's star is still in the ascendant.

Edward Herman to Myrtle Knister

1 September 1932

Dear Mrs. Knister,

It is not a time to bother you, but I felt I must write. I heard the news of Raymond's death in Montreal and was terribly shocked; and grieved, as much for his sake, as for yours. Though I saw him only for a brief about three weeks ago, I was worried about his future, for the game of writing he had chosen has become such a precarious one these days. Moreover the stories he showed me I did not like so well as some of his previous work, and I told him so. But I have always been very interested in his work, it showed an inspired and profound mind. For this reason I would like to ask if there is anyone now in charge of his manuscripts—Pelham Edgar or Morley Callaghan—and if not, whether you would consent to let me see them. He has told me his plans about a play about his stories and poems and it might very well be that I could interest Mr. Eryrs of Macmillans in this publication. I should like very much to try. Doubtless you realise that such a venture would be a help to you, financially. My own interest is purely a personal remembrance, a wish to do something for so good a friend.

Could I see them? Perhaps I could come to Port Dover if there is too much to be put through the mails? What is your house address there?

Believe I am sincerely troubled by all this sorrow that has come to you. —are there no more intimate details of what actually happened than what appeared in the paper? Is there no hope of finding the body?

—Forgive me if I have interfered. It is because I would like my sympathy to be of some use.—

Very Sincerely yours,

Dorothy Livesay

2 September 1932

Dear Mrs. Knister;

Please accept my deepest sympathy. I was shocked beyond measure on learning of the tragedy. My wife and I feel with you in your grievous loss. The personal loss to you and the children is, I know, beyond estimate and the loss to Canada and to Canadian literature cannot be reckoned. He had accomplished so much worth-while in a few years, against the terrific odds which confront a writer striving to maintain sincerity and integrity in his work in this country, that he was obviously one of our few genuine artists. The blind eradication of that power and sensitivity is a stunning and bewildering blow. I am glad that I was privileged to meet him even for a few moments during his lifetime and while I know that words are feeble things in the face of such disaster I wanted you to know that our hearts are with you at this time.

If there is any possible service I can render in a professional capacity please accept my assurance that I shall be only too happy to be of any help.

Yours very sincerely,

Leslie McFarlane

5 September 1932

Dear Mrs. Knister:

Friends of Raymond Knister, and they are everywhere I am sure, are haunted by his tragic loss. To me the sorrow is a great and personal one, and I assure you of my profound sympathy.

Raymond came to me with his novel on Keats, and I believe that I was among the first to praise it, hazarding the opinion that it stood a good chance in the Graphic Contest. Later he told me of their failure, and asked me to assist in retrieving it, so that it might be published, earn royalties, and above all protect the copyright. After a great deal of correspondence I was able to purchase the standing type, when the legal tangle, following bankruptcy proceedings, had been cleaned up. I am happy to think that he learned of our success before he went. Later I had planned to send a contract, and settle the date of publication.

He was anxious to find employment, and it was my hope that we could make an opening at The Ryerson Press. As you know, times are trying, and we were anxious to hold our staff without dismissing any or cutting salaries. To engage new help, in view of this, was a real problem, yet I hoped to solve it. In the meantime I promised some personal work, and he had written accepting it. Raymond followed with another letter, telling me of your camp, and expressing his eagerness to get in to Toronto and at work. He wanted an advance by return. The letter was addressed to my office, and I, being out of town on vacation, did not receive it until a few days later, when I went in for an hour or so. I brought my mail to my cottage, and wrote him at once, saying that I was enclosing a cheque. The next morning I motored back to town to mail it, and when I reached my office word was awaiting me of his lamentable passing.

He was a rare spirit, and it would have given me great joy to help him.

I shall send the contract to you soon. Will you command me in any way?

Your friend,

Lorne Pierce

62 Delaware Ave.,

Toronto, Ontario, Canada,

Now. 27th, 1940.

Dear Mr. Gustafson, —

While I never knew Raymond Knister, I learned something about him from a friend. He never published a book of his verse, but probably would have done so. He was about to return to Toronto to live when he was drowned in the fall of 1932.

Immediately before his death a group of his poems appeared in The Canadian Forum along with an article by Leo Kennedy. I have copied out the group in its entirety.

A group of seven poems appeared in The Midland of December 1921. Enough poems have appeared in American poetry magazines to form a small volume but they are still uncollected. He lived twenty years on an Ontario farm, died at 32. He worked on The Midland, also for Poetry. He placed short stories and poetry with This Quarter (Paris, in the late twenties).

He had not become well-known and I am anxious to help make sure that he doesn't get overlooked, which might possibly happen as anthologists hereabouts show a tendency to follow a well-worn track.

Yours sincerely,

W.W.E. Ross

13 October 1945

Owing to Dr. Pierce's limited time and health, he passed the task of preparing "Windfalls for Cider" to me, as well as the writing of the memoir on Raymond Knister, my mother and I knew him quite well in a literary way, so the main emphasis will be on that side of his life. There are however several biographical details which I need as background and also to explain why he wrote and how he wrote...

You will be interested to know that I read some of the poems in a lecture recently on Contemporary Canadians, and they were wonderfully well received. I read first the White Cat, but several more were asked for. I think the book should become really popular and of great literary interest.

Letter from Mrs. Duncan Macnair to Mrs. Myrtle Grace (nee Knister)

November 1945

I am startled to discover that in the little time since Raymond was drowned, (1932-3) a legend has sprung up that is as utterly cock-eyed as you'd expect one to be in a century. I was working on the Montréal Herald the day the news came, and promptly some mugs who worked on that feeble sheet started nodding their heads wisely and saying, 'Ah yes, Knister, a suicide of course.' Presumably with as little basis, similar specimens did the same thing in Ontario. If anyone was close to Raymond Knister in his last year, I was, and I will swear on as high a stack of Bibles as you elect that the man drowned. What is more, I shall be happy to go into print and fight the first published inference that such warn't the case. I shall fight you, if you like. And I've a docket of evidence and argument as long as your arm. When Raymond Knister drowned, with his wife screaming at some lounging oafs to go to his rescue, he was on the way up. He was through with the crazy Graphic business; lawyers had nicked a good piece of his prize money but he did have the bulk of it. We had just read the proofs of the Keats novel. Macmillan had made a deal with him to serve as a reader at a price. Economically he was in the clear. What's more, he felt, as he wrote me from Ontario (I was still in the depression in Quebec), all his creative powers quickening. Everything was going good for that guy and he knew it. He said it. He wrote it too me. These are some of the reasons why I shall be most happy to knock the block off the first sensationalist who starts construing his tragic death as self-destruction.

Leo Kennedy to Dorothy Livesay

16 June 1949

To me there are two mysteries about Raymond. One, of course, was the mystery of his death which still depresses me when I think about it. What could I have done that I did not do? And I wonder why, but no one can say. Certainly his work was done, at least done in a matter far beyond his years, and his influence is abiding. The second mystery is how a boy so young, from a farm, almost without academic training, should naturally move into his rightful place beside the most creative and progressive minds of his time, how could he unerringly place his finger on the great long before it became recognized and point out the shoddy even while it was being acclaimed.

I have changed the reference to Morley Callaghan. I agree with you that it might sound unfair. I put in its place Sir Gilbert Parker, who is a classic example of a man who sold out to the commercial.

Letter from Lorne Pierce to Myrtle Grace

19 May 1949

Miss Margaret V. Ray,

Associate Librarian,

The Library,

Victoria University

Toronto

Dear Miss Ray:

I did not get to know Raymond Knister until shortly before his death which came as a great shock to me because on,his last night in Toronto he came to my house and stayed until the small hours, urging me to keep on reading a partly finished manuscript of mine, later published as "Think of the Earth".

His eagerness to know what other writers were doing and his encouraging constructive comments on their work were indicative of a generous attitude toward competitors which unfortunately is all too rare.

While it was obvious that he had read widely and was alert to current trends, his conversation was free of sophistication and artiness, being redolent rather of earth and growth and weather and simple souls.

In My Star Predominant, of course he was dealing with another world, another time, and with the tortured complex nature of a young poet of immense gifts. His study of Keats, however, although dealing with works of imagination of the highest order, matches in the humility of his treatment the humility he shows, mixed with exalted egotism, in the nature of Keats. There is a fine passage of dialogue which paraphrases the famous letter regarding the "negative capability" of the poet, and one feels as one reads that Knister was not so much creating something as absorbing and revealing what he had learned of Keats' creative achievement.

There is a slightly archaic tone throughout the book which helps to carry us back to the tune and the people who were drawn into the circle of Keats' life. Few Canadians have attempted such a task, let alone carried it through to so satisfactory a conclusion.

The only other work of Knister's which I can remark on with any degree of familiarity is an unpublished manuscript titled "The Innocent Man" which he left with me to read. It was our intention to have a session on it later, but I never saw him again.

The manuscript, which I turned over to Dr. Lorne Pierce, is of novelette length and concerns a convict. If I remember correctly the story takes place entirely within the prison walls. There is little action, but I can still recall the trueness of the dialogue between the cell-mates. It is close to being typical of so many manuscripts written by Canadians whose independence prevents them from following leads or pandering to a market.

Had he lived, Knister's robust mind, generous heart, and exceptional gifts, would undoubtedly have contributed in an outstanding way to Canadian literature.

Sincerely,

Bertram Brooker

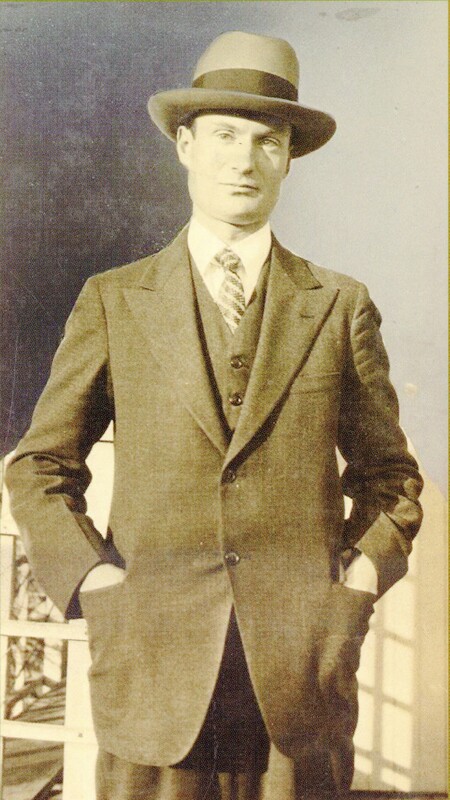

Morley Callaghan on Raymond Knister

Raymond was - well, I would say, a rather good-looking man. He had a sensitive face and his forehead was enlarged by a kind of premature baldness which was really just at the front of his head which gave him a very dignified and rather an interesting intellectual appearance—but I'll tell you the peculiar quality about Raymond—he had very interesting eyes—they used to irritate me a little, these eyes of Raymond's—they were good eyes and in a sense they were the eyes of a writer but they were also the eyes of an enormously self-conscious man. Now you might be talking to Raymond—say—if you were in a room with six or seven people—and then you would notice that Raymond was not talking directly to you—he would be talking to you—but these eyes of his—you know—they'd be wandering all around the place—the eyes of either a nervous man or a self-conscious man or a man intent on knowing what was going on behind him, in back of him, in front of him, so you always had the feeling that he was in four or five places.... Raymond knew what was going on in London and New York, Paris and so on. I couldn't figure the guy out—I mean—this was what was strange to me about Raymond—how did this boy, off the farm—you know—have this taste and understanding about writing? I have no idea how he got this way—this was what [was] so strange about him among Canadian writers. He was the only guy I knew in Toronto at that time—who, you know, that I might do a story and I could take it to Raymond and I would know that Raymond was reading this story just as someone in New York or Paris might read it and his judgment was just as good. Raymond knew what was good! In any time and in any period, these men are very rare—and Raymond had this peculiar taste and understanding about literature....

And this is where we sort of went two different ways—I was interested in talking with Raymond, but Raymond sort of knew everybody. He had this hunger to know writers—you know—so he would go off visiting Charles G.D. Roberts and Wilson MacDonald and Mazo de la Roche and so on, and he'd come back reporting to me about them...

Excerpt taken from CBC Radio Show "The Farmer Who Was Also Poet." Produced by John Wood and Allan Anderson. 19 July 1964.

Arthur Stringer came to Toronto in November 1928 and the Writers' Club invited him to speak. This drew a large crowd and excited unusual interest. Arthur Stringer was not only what women called "a gorgeous hunk of a man" but he was outstanding among Canadian authors of his day for sales and earnings. There was secret envy in the Toronto writing world, mingled with open admiration for his achievements. (25)

Raymond Knister and his wife occupy the suite just above us. I am constantly hearing the intonation and the sentence rhythm; though never the words, of a Canadian author, as I sit in my living room at my portable type-writer. Before I finish these notes I am sure to hear the low vocal vibration, and the step of his foot immediately above me. When Raymond starts typing (on a portable, like my own) a subdued clicking is also audible. Thus I can hear the slow growth of a Canadian novel that, for all I know, may set the literary Thames on fire. (28-9).

from Literary Friends. Wilfrid Eggleston. Borealis Press, Ottawa 1980.