“Knister came of age in the 1920s. Both his life and work seem to reflect the steady drift from an agrarian society to an urban one. As a poet, he moved ever closer to the world of William Carlos Williams. At the time of his accidental death by drowning, he was well along the road to the simple direct statement of the modernist lyric.”

George Fetherling in The Vancouver Sun. Vancouver, B.C., April 3, 2004, page. D. 16.

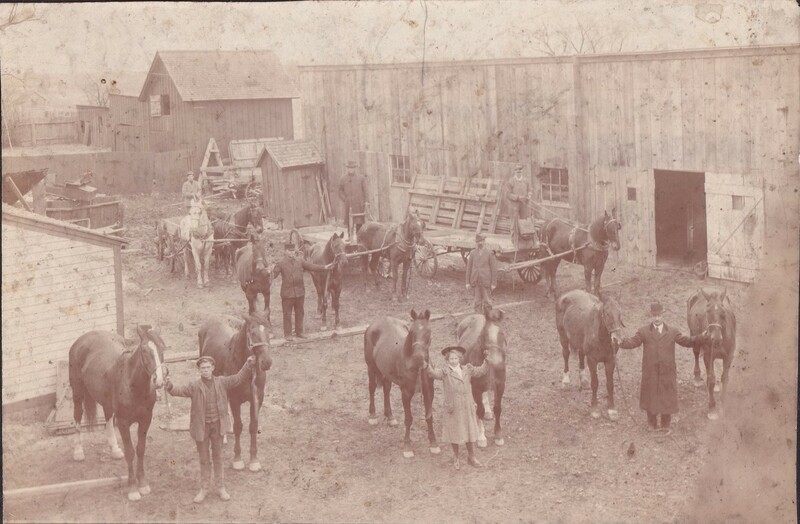

Knister wrote about “A Row of Stalls” in a letter to Olaf P. Reichnitzer in 1930: “A dozen free verse poems about horses which I had published in This Quarter in Pariz, might give you a better notion of my capabilities. The language could not be plainer, nor the material more homely. Yet a definite impression is made in each case, I think, along with some sense of the life which produced them. The art which conceals art seems to me best...”

From After Exile edited by Gregory Betts. (Exile Editions, 2003, page 84)

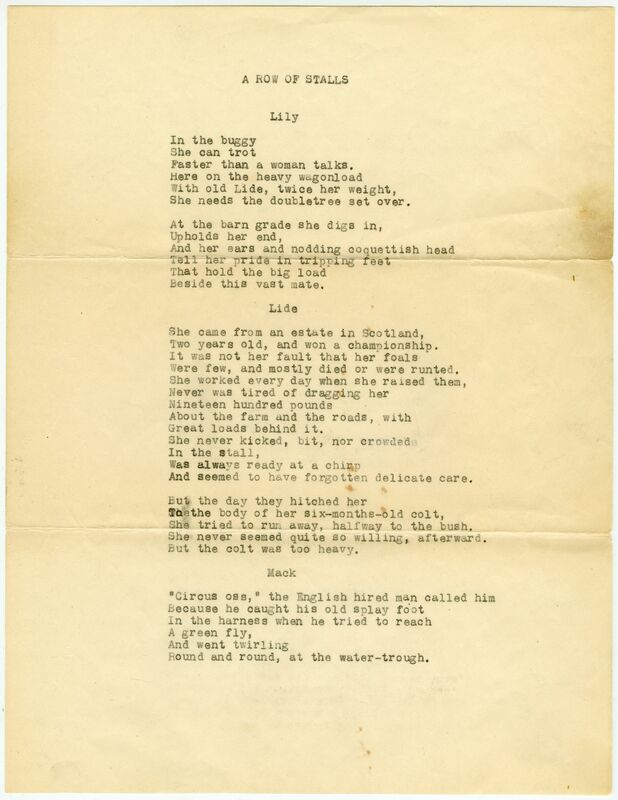

A Row of Stalls

Lily

In the buggy

She can trot

Faster than a woman talks.

Here on the heavy wagonload

With old Nell, twice her weight

She needs the doubletree set over.

At the barn grade she digs in,

Upholds her end,

And her ears and nodding coquettish head

Tells her pride in tripping feet

That hold the big load

Beside the vast mate.

Nell

Nellie Rakerfield

Came from an estate in Scotland,

Two years old and won a championship.

It was not her fault that her foals

Were few, and mostly died or were runted.

She worked every day when she raised them,

Never was tired of dragging her

Nineteen hundred pounds

About the farm and the roads, with

Great loads behind it.

She never kicked, bit, nor crowded

In the stall,

Was always ready at a chirp

And seemed to have forgotten delicate care.

But the day they hitched her

To the corpse of her six-month-old colt,

She tried to run away, half way to the bush.

She never seemed quite so willing, afterward.

But the colt was too heavy.

Mack

“Circus ‘oss,” the English hired man called him

Because he caught his old splay foot

In the harness when he tried to reach

A green fly,

And went twirling

Round and round, at the water trough.

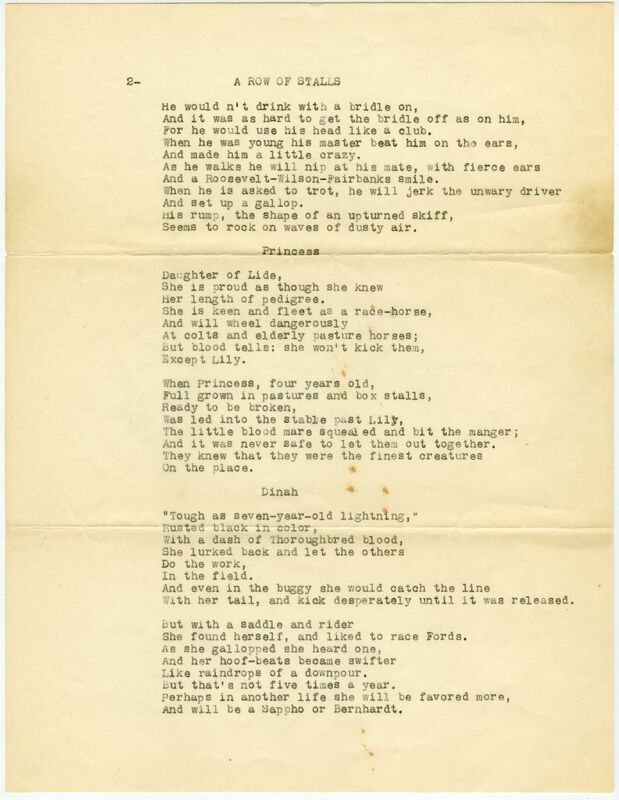

He wouldn’t drink with a bridle on,

And it was as hard to get the bridle off as on him,

For he would use his head like a club,

When he was young one master beat him on the ears,

And made him a little crazy.

As he walks he will nip at his mate, with fierce eyes

And a Roosevelt-Wilson-Fairbanks smile.

When he is asked to trot, he will jerk the unwary driver

And set up a gallop.

His rump, the shape of an upturned skiff,

Seems to rock on waves of dusty air.

Princess

Daughter of Nell,

she is proud as though she knew

Her length of pedigree.

She is keen and fleet as a race-horse,

And will wheel dangerously

At colts and elderly pasture horses;

But blood tells: she won't kick them,

Except Lily.

When Princess, four years old,

Full grown in pastures and box stalls,

Ready to be broken,

Was led into the stable past Lily,

The little blood mare squealed and bit the manger;

And it was never safe to let them out together.

They knew that they were the finest creatures

On the place.

Dinah

"Tough as seven-year-old lightning",

Rusted black in colour,

With a dash of Thoroughbred blood,

She lurked back and let the others

Do the work,

In the field.

And even in the buggy-shafts she would catch the line

With her tail, and kick desperately until it was released.

But with a saddle and rider

She found herself, and liked to race Fords.

As she galloped she heard one,

And her hoof-beats became swifter

Like raindrops of a downpour.

But that's not five times a year.

Perhaps in another life she will be favoured more

And will be a Sappho or Bernhardt.

Cross-bred Colt

It gets its way

Among the bigger colts

Without kicking or biting,

By sheer fierceness of expression,

Seeming to know that it has no name,

And that nobody will care,

Until it is big enough to work.

The only time its ears were not flattened back

Was when the hired boy, tired

Of its regularly striking and tipping the waterpail

When the others crowded it,

Swung a clip to its muzzle.

It turned away and stood awhile,

Ears pricked

Considering – the first contact with man –

Or was it pure surprise?

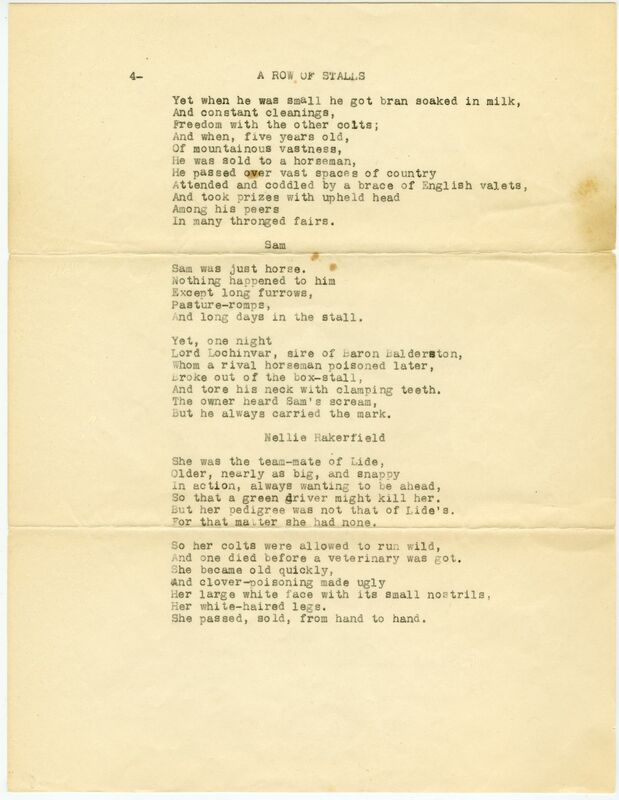

Baron Balderston

From the high window of his narrow box stall

He could see the sunshine,

The colts wheeling in the lane,

Old Nell his dam on the three-horse disc-harrow,

But he never got out.

Yet when he was small he had bran soaked in milk,

And constant cleanings,

Freedom with the other colts;

And when, five years old,

Of mountainous vastness,

He was sold to a horseman,

He passed over vast spaces of country

Attended and coddled by a brace of English valets,

Among his peers

In many thronged fairs.

Sam

Sam was just horse.

Nothing happened to him

Except long furrows,

Pasture-romps,

And long days in the stall.

Yet, one night

Lord Lochinvar, sire of Baron Balderston,

Whom a rival horseman poisoned later,

Broke out of the box-stall

And tore his neck with clamping teeth.

The owner heard Sam's scream,

But he always carried the mark.

Nance

"She kicked her foot throught the dashboard,

And I made her go, for about a mile."

The old cattle-dealer's booming voice,

Like that,

Must have lent speed to her three legs.

Then when they got home

He carefully unharnessed her,

Clutched her bridle in one hand,

Half a rail in the other,

And the dance began.

When Art Huffer got Nance,

He declared that he would cure her.

He took ten bushels of corncobs

Into the loft above her stall;

All the rainy day he dropped cobs

And as each one struck her

She kicked as high as ever:

Art had to give up too.

Lide

She was the team-mate of Nell

Older, nearly as big, and snappy,

In action, always wanting to be ahead.

So that a green driver might kill her.

But her pedigree was not that of Nellie Rakerfield' s.

So her colts were allowed to run wild,

And one died before a veterinarian was got.

she became old quickly,

And clover-poisoning made ugly

Her large white face with its small nostrils,

Her white-haired legs.

She passed, sold, from hand to hand.

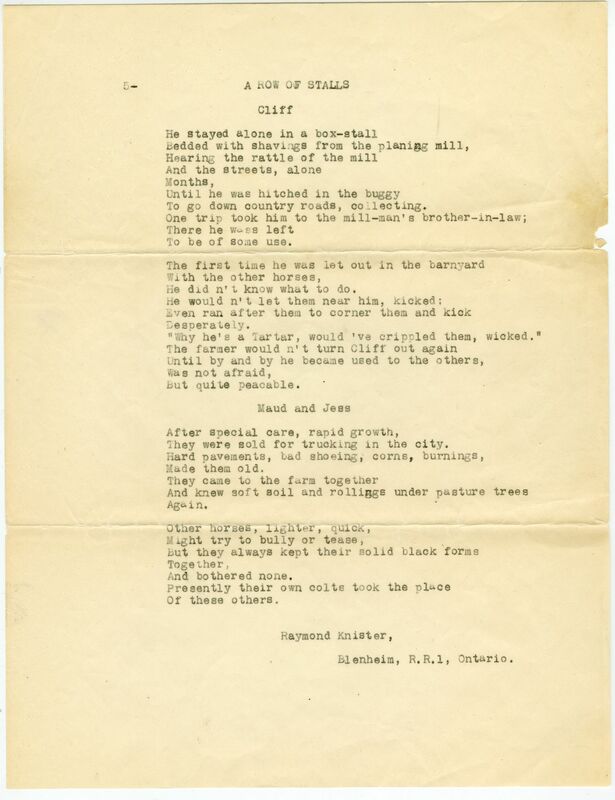

Cliff

He stayed alone in a box-stall

Bedded with shavings from the planing mill,

Hearing the rattle of the mill

And the streets, alone

Months,

Until he was hitched in the buggy

To go down country roads, collecting.

One trip took him to the mill-man's brother-in-law;

There he was left

To be of some use.

The first time he was let out in the barnyard

With the other horses,

He didn't know what to do.

He wouldn't let them near him, kicked:

Even ran after them to corner them and kick

Desperately.

"Why he's a Tartar, would've crippled them, wicked."

The farmer wouldn't turn Cliff out again

Until by and by he became used to the others,

Was not afraid,

But quite peaceable.

Maud and Jess

After special care, rapid growth,

They were sold for trucking in the city.

Hard pavements, bad shoeing, corns, burnings,

Made them old.

They came to the farm together

And knew soft soil and rollings under pasture trees

Again.

Other horses, lighter, quick,

Might try to bully or tease,

But they always kept their solid black forms

Together,

And bothered none.

Presently their own colts took the place

Of these others.

(After Exile, page 85-92)