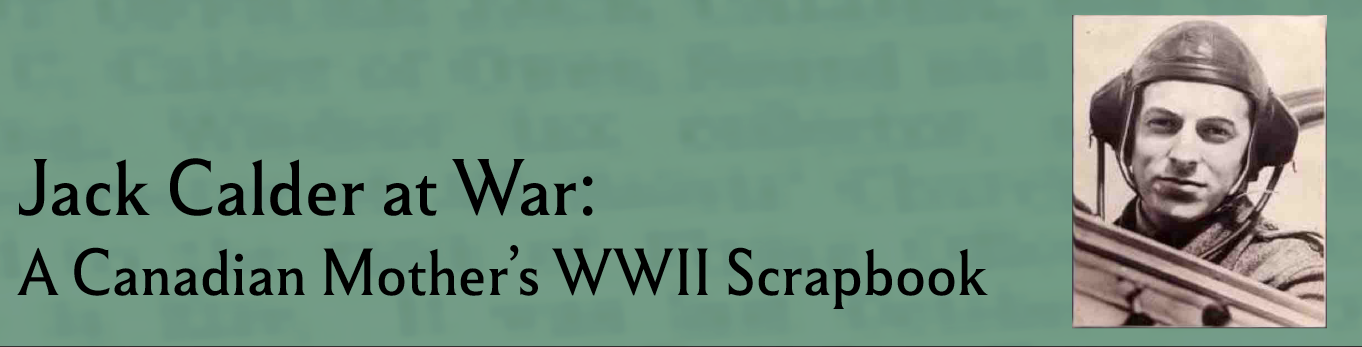

Agnes's Story by Patricia Calder

December, 1939

When we gather for Christmas, Jack requests that we take a group portrait that he and his brothers can carry in their breast pockets when they go to war.

Philip (front row, left) is just finishing high school at age 18. Marjorie, 19, (beside Philip) is working in Toronto at Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce. Mary, 20, (middle row) is training as a nurse at St. Joseph’s Hospital in London. Jake, 27, (front row, right) an instructor of army recruits in Toronto, is trying to recruit his younger brother.

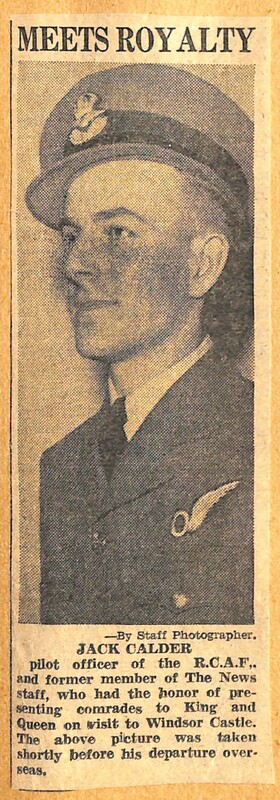

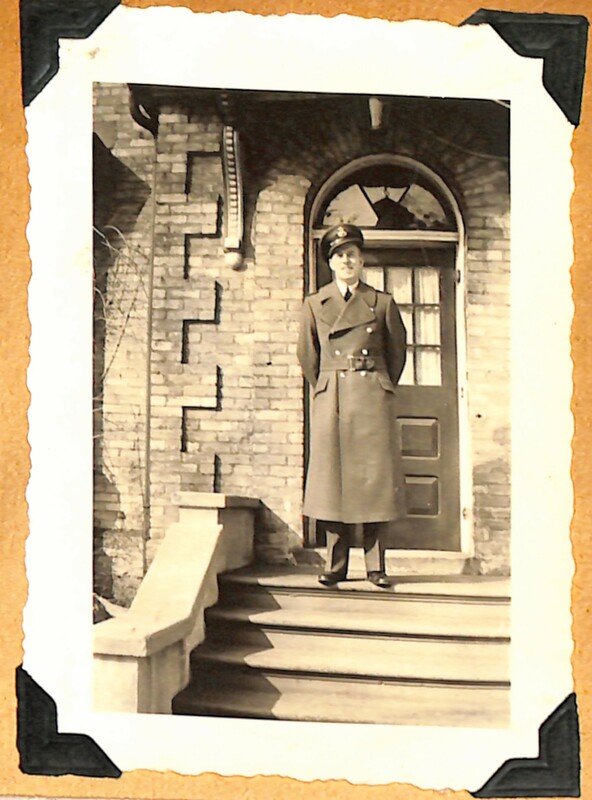

Jack, 25, (back row, right) has been a sports editor with the Canadian Press. He has enlisted in the Air Force, and is about to be deployed in January.

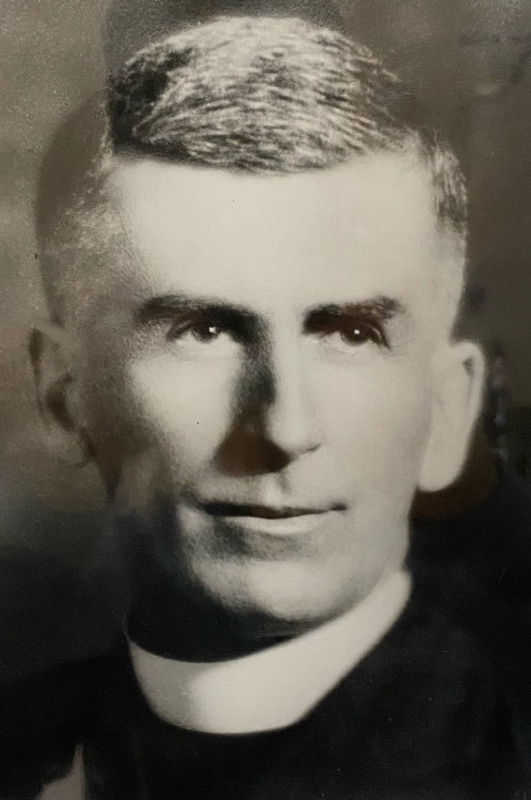

My husband, the Reverend A.C. Calder, (I call him Archie) (at the back, left) is 60 this year. He is an inspired preacher. In 1934, he ended his second term as a Member of Provincial Parliament for Chatham-Kent. He has recently been moved by the Anglican Bishop from Goderich to Owen Sound, St. George’s Church.

That’s me, beside Jake, Agnes Calder, 50, adjusting to a new home and parish, finding my purpose in war time as the mother of three sons who will soon all be overseas.

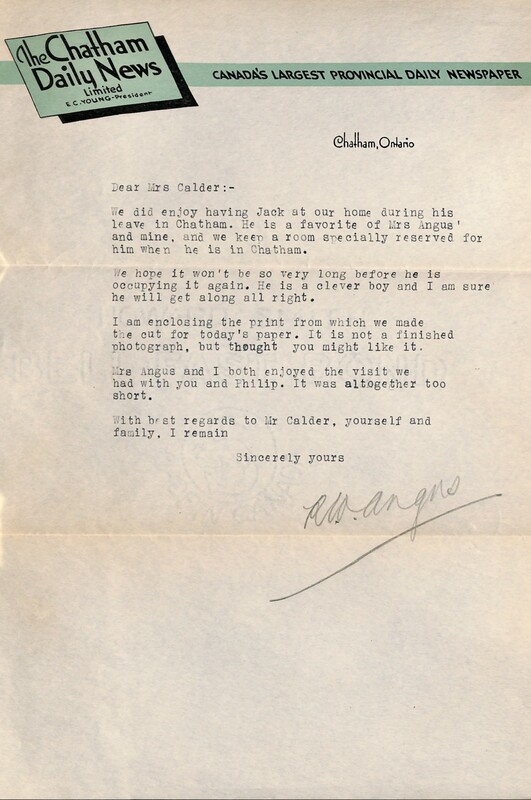

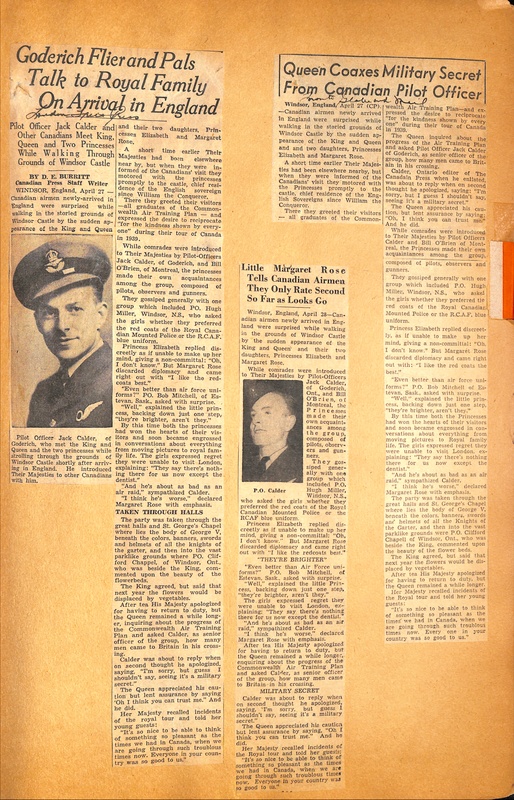

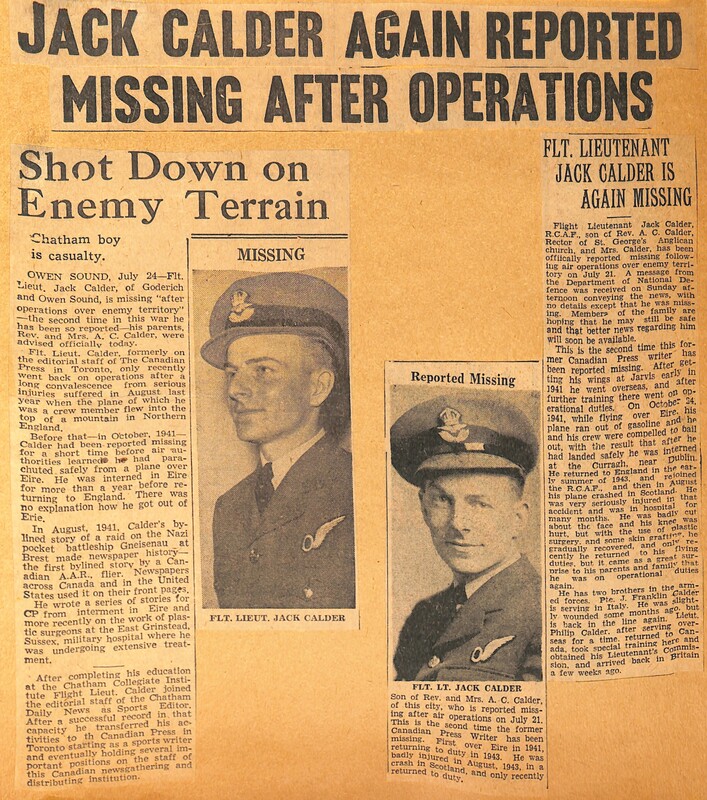

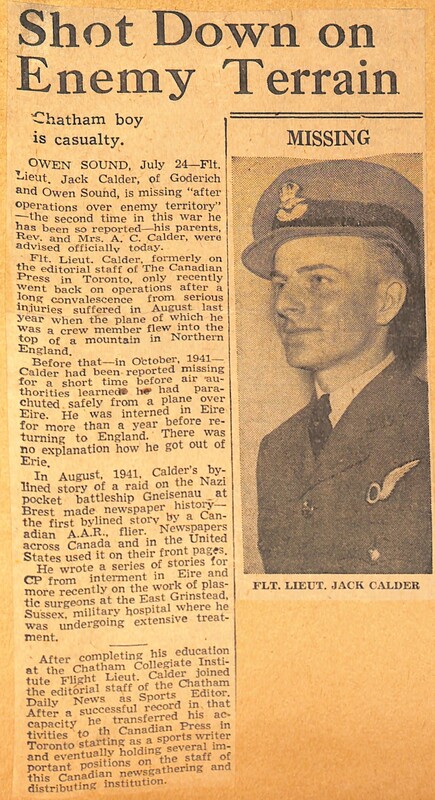

Whenever Jack’s name is mentioned, Canadian Press perks up its ears and publishes a story. I am so grateful that friends and relatives all over the country mail clippings to us.

There's a picture of Jack where it appears as he is trying on a parachute. The thought of his having to parachute out of a plane fills me with dread, but I suppose it could save his life.

I am receiving more mail than I have in my entire life. I have confiscated half the dining room table as an office because I need space to sort my correspondence. Archie has a den as the parish priest, but with this war on, we mothers will also be engaged in writing letters.

The next one asks for $50 to be cabled to the Canadian Press Bureau because Philip is coming. I expect the two of them will go out on the town. He also remembers my birthday. Ironic that he’s asking me for a gift this April 22nd.

I long for letters. Jack says he’s working hard. Letters would explain more detail; however, they might be censored by the boys with black markers.

I must be content with telegrams. A telegram from him means he’s alive.

I am thrilled to hear the very kind words people say about my sons now that they are overseas.

April 8, 1941

Jack’s boss in the Canadian Press, Andrew Merkle, writes personally to us that Jack is a fine fellow.

Andrew is probably a father himself, so he understands my anxiety and reassures me. I shall treasure this letter. I don’t believe that a boy of good character has any better chance of coming home, but I want to believe it.

It’s funny that letters mention how happy my son is to be going to war. What an odd thing to say. It’s meant to be reassuring but doesn’t quite do the job. When I looked into Jack’s eyes our last evening together, there was a moment of silent communion between us. A mother knows what is in her son’s heart when it’s too complicated for words.

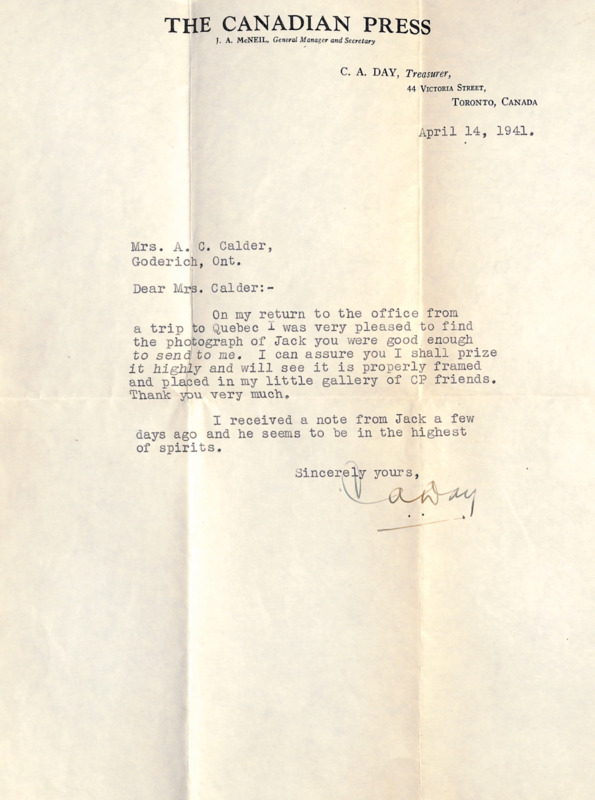

A letter arrives from the Canadian Press head office. The Treasurer, C.A. Day plans to frame the picture of Jack I sent him and add it to his “little gallery of friends.” I am deeply moved that people I don’t even know care so much about my son.

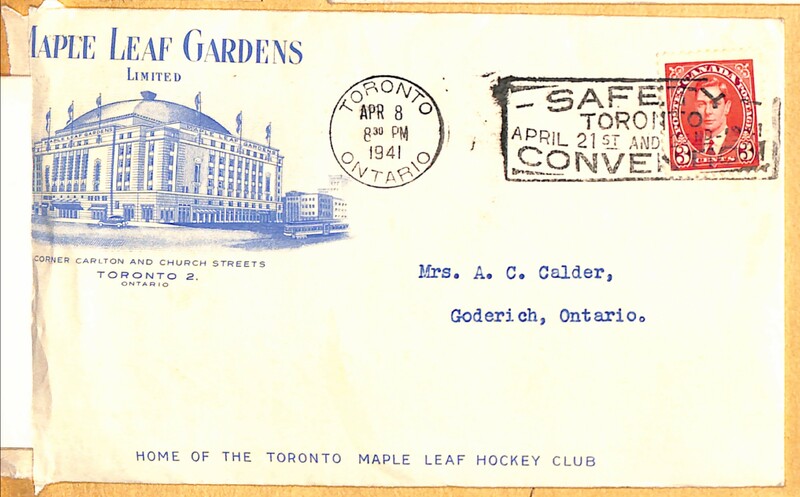

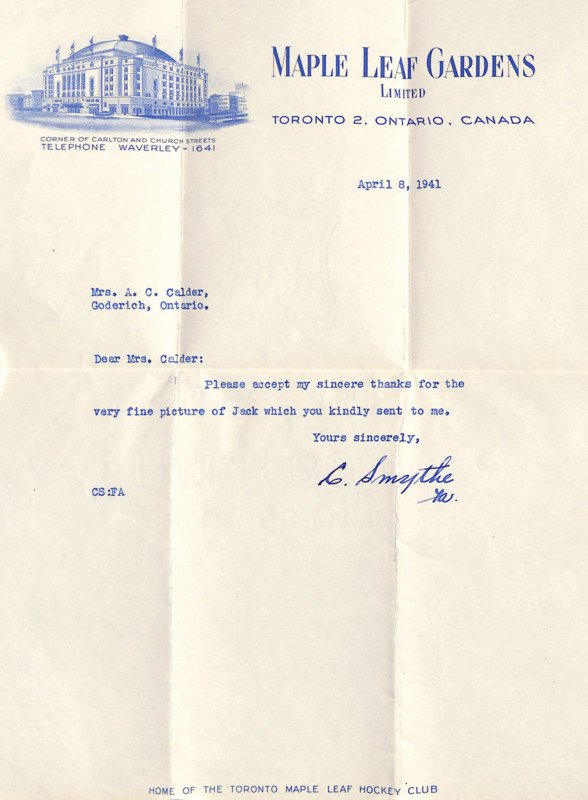

Today I open an envelope with a very grand logo of Maple Leaf Gardens at the top of the page.

I shall keep it for the signature–owner of the Toronto Maple Leafs, Conn Smythe. I am surprised that my son moves in circles of the rich and famous as he doesn’t brag to his family about these connections. At home he is simply one of us.

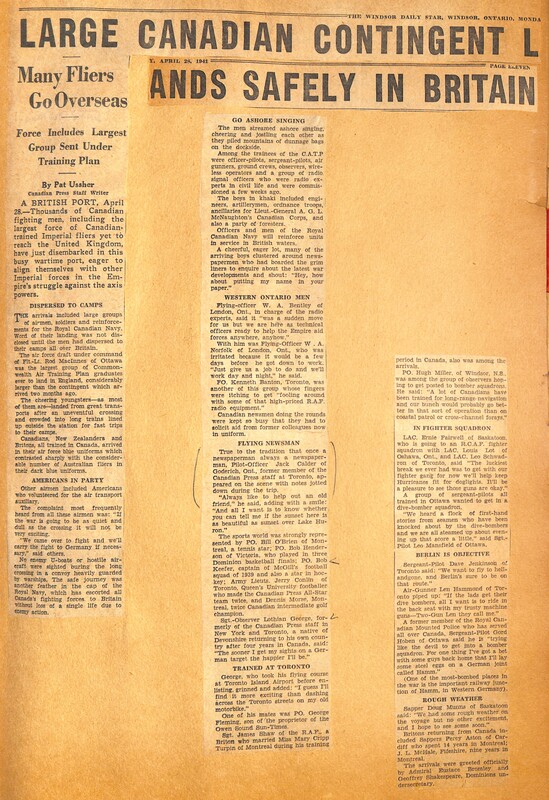

The mail is exciting for the last few days. News clippings are arriving from all over— the Globe and Mail, Toronto Star, London Free Press, Windsor Star, as well as the Chatham Daily News.

Canadian Press is circulating the story everywhere of Jack and other airmen meeting the Royal Family, even having tea with them over an extended conversation.

Is this truly wartime for these men? Jack and the others have obviously not been exposed to the full impact of conflict yet.

The Queen mentions "hard times" but she hasn’t seen battle first-hand; she’s been protected in Windsor Castle.

How surprising that the Royals rush to meet the Canadians. We tend to think of them as high and mighty, but at the bottom of it all, they’re just people like us. They have their hopes and dreams, and who said, “They pee in a pot the same as us.”

The visit finishes with a history lesson, to restore the gravitas of the crown and to remind these lads why, in a few short days, they will be risking their lives to preserve and protect it.

I wonder when the risk will hit them, as it has hit us, the mothers and fathers at home.

July, 1941

Jack wrote a letter to the Chatham Daily News. I’ve received a copy in the mail this morning. He tells stories of the Brits he’s met and ends with a very personal note: “And now I’m set down on a station outside a pretty little English village. After two nights with the Canadian Press boys in London, both my pocketbook and I are ready to plunge deep into hard work.”

This paragraph sinks into my heart. He has a way of addressing me in his words to the public. He is reminding me of the cups of tea, and occasional drams of Irish whiskey we shared late at night in our screened-in porch in Goderich. I hear you, my boy. I hear you.

August 13, 1941

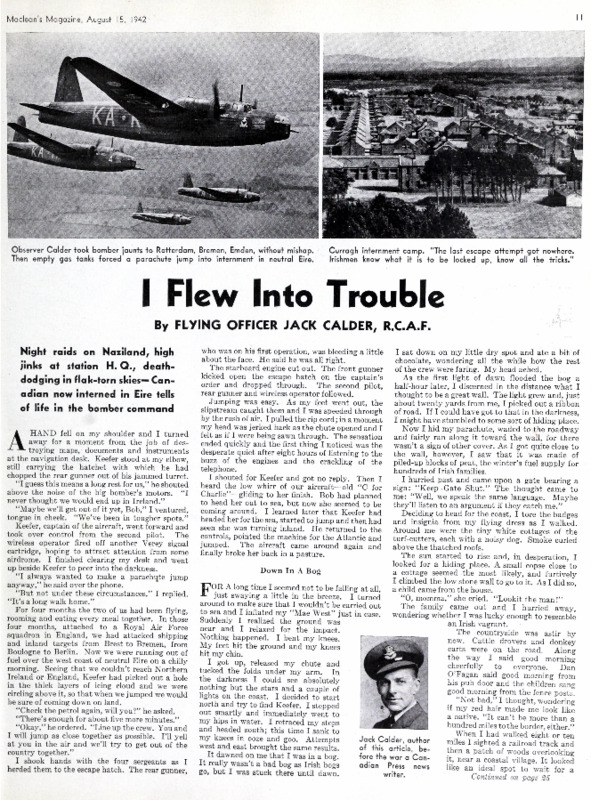

I am thunderstruck! Jack participated in leading an attack on the German pocket-battleship Gneisenau. His story takes me right inside the aircraft during a mission. As navigator he not only directs the captain where to fly, he informs the smallest details of the flight toward the target, right up to the moment the bombs drop. Jack’s instructions affect two other aircraft flying in formation behind him. I am in awe of my own son. He is using those leadership skills he learned as a youth when he was member of two or three sports teams and editor of the school yearbook.

Through Jack’s story-telling I learn a little about the relationships among the crew, how they communicate during the attack. The respect owing to the captain is flavoured with good natured teasing, calling him “Slapsy Maxie.” He holds their lives in his hands. They depend on his cool temperament in a tense situation when they are under enemy fire, or when a friendly bomb descends from the plane above and nearly wipes them out.

I’m learning new words: antiaircraft shell bursts, barrage balloons, ack-ack, evasive action, drift wires, dry docks, and mess.

As a mother I note that the men don’t wear their parachutes all the time; they put them on when the going gets tough.

I feel proud that my son is playing a role in making history; however, this story leaves me terrified. I will not sleep tonight.

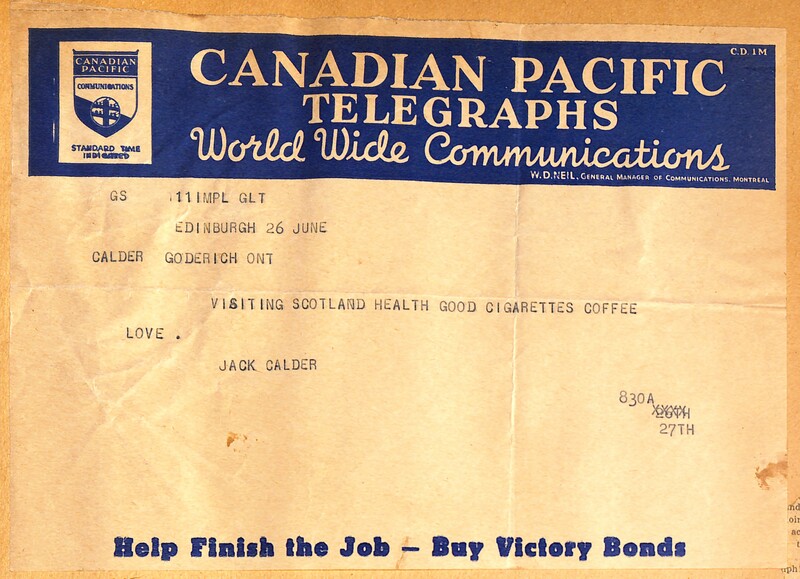

Jack sends me telegrams when he doesn’t have time to write a proper letter.

Telegrams are rather cryptic. I have to interpret what he means; for example, this one ends “cigarettes coffee.” Does that mean “Thank you for your care package containing cigarettes and coffee” or “Cigarettes and coffee needed urgently?”

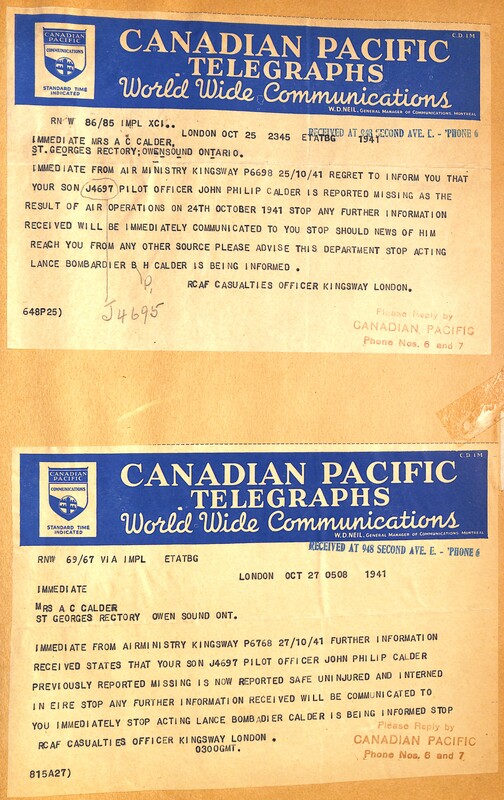

October 25-27, 1941

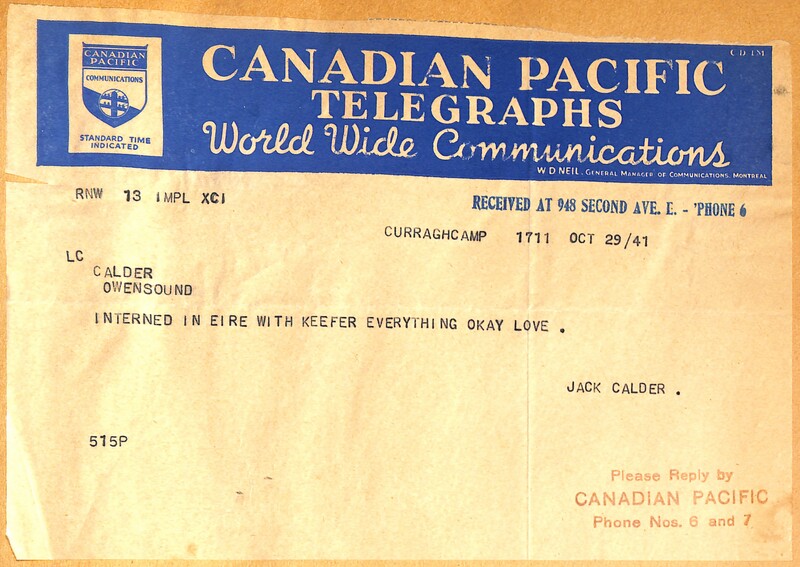

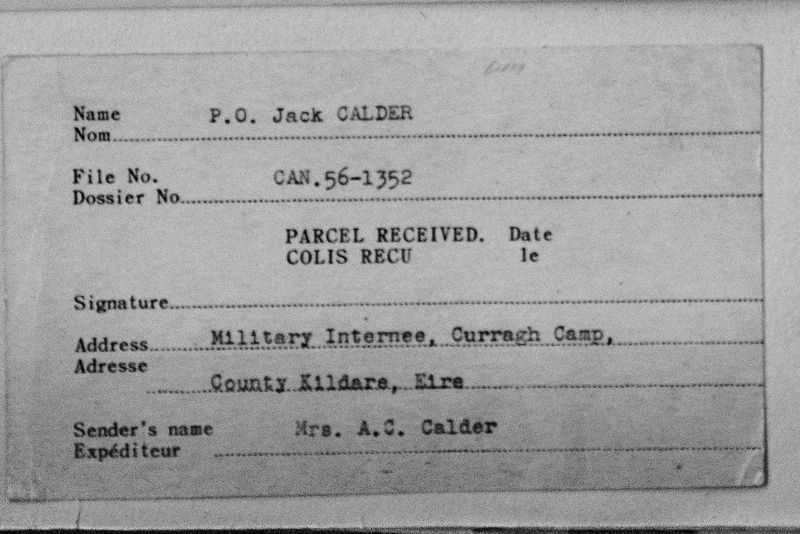

Two telegrams have sent us on a roller-coaster of emotion. First that Jack is missing in action on October 25th. We didn’t sleep until we heard by telephone from CP on October 27th that he is alive, in prison in Eire. Then we received the second telegram on October 27th confirming the information.

Eire is not part of the UK (as is Northern Ireland); hence it is neutral. They take prisoners from both sides; anyone who lands on their territory or within three miles of its shore is collected by the guards.

No word yet from Jack. I wonder how he is being treated as a POW.

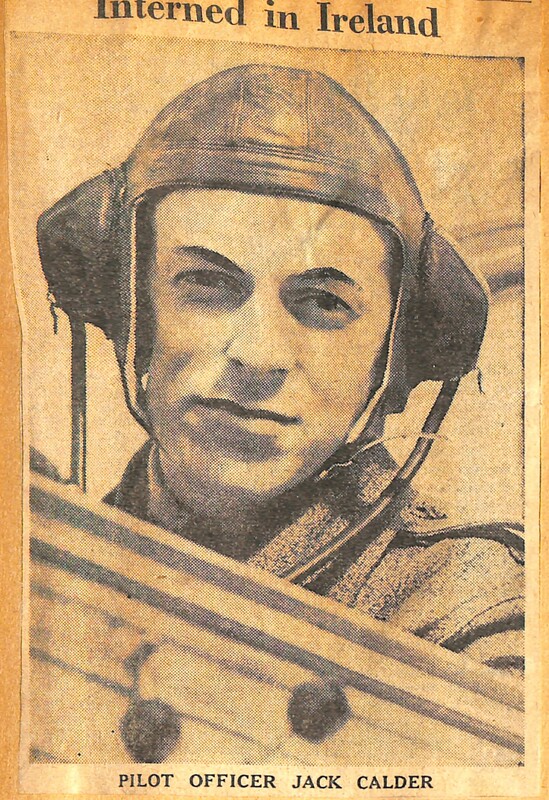

Details of Jack’s crash and arrest are leaking out, one news story at a time.

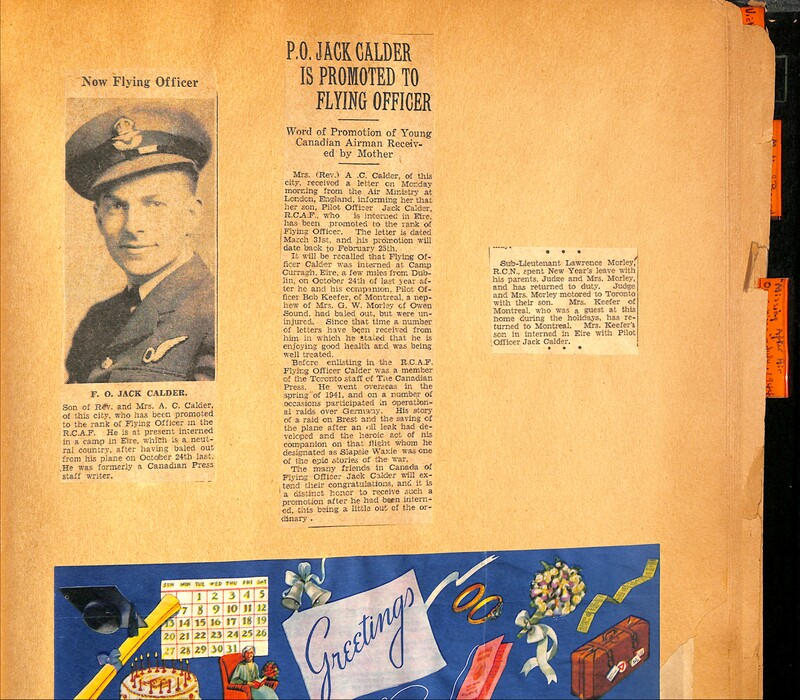

Today we learn that Jack has been promoted to the rank of Flying Officer. CP advises that it is very unusual for an officer to be promoted in prison. I must confess, I feel an inkling of pride.

Now the newspapers are printing the story of Jack’s plane crash and arrest. It’s being circulated by Canadian Press everywhere that has a connection to one of the lads in Jack’s crew, lads like Bobby Keefer.

Because of Jack’s story about the bombing of the Gneisenau, his name is big all over.

When Jack was MIA, the reporters at CP had half-finished an article that reads like an obituary!

Jack’s imprisonment in Eire instead of Germany is a relief to me, although Archie tells me that the Curragh prison is rebel territory and the guards are likely former IRA. I wonder what life will be like for him in camp.

Why is Eire taking prisoners since Britain just saved it from the Nazis? One of Germany’s goals in the Battle of Britain was to take over the Irish ports as a launching pad to UK. We hear rumours of Nazis docking in Belfast port and mixing with the locals in certain pubs.

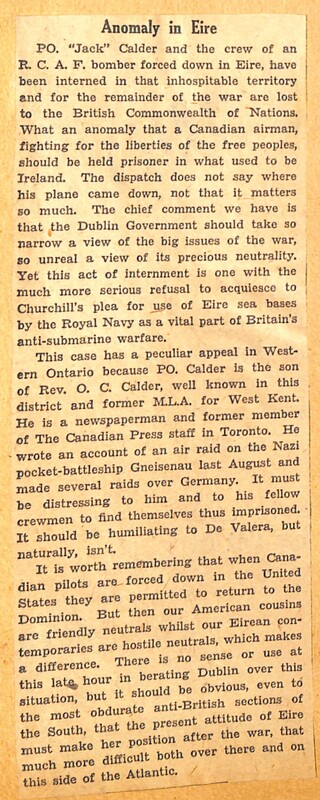

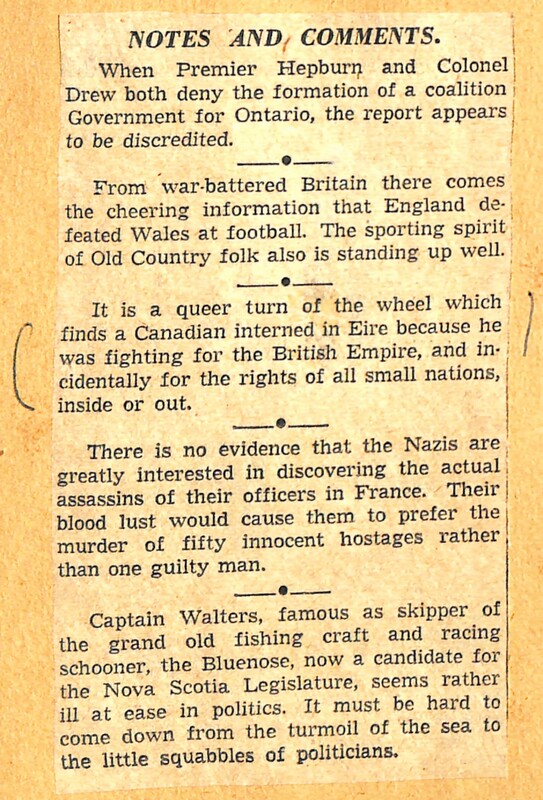

A tiny strip of news column is striking in the level of its anger towards Eire. Its tone uses phrases such as, “inhospitable territory,” “Dublin government should take so narrow a view…so unreal a view of its precious neutrality,” “should be humiliating to De Valera (the Prime Minister), but naturally, isn’t,” and ends by calling Eirean contemporaries “hostile neutrals.”

Hatred for the British is still very strong in Northern Ireland.

Churchill pleaded with the Dublin government to give the Royal Navy access to Eire’s sea bases as a vital part of Britain’s antisubmarine warfare. The Irish Sea is rife with U-boats. Dublin refused.

Irish politics is confusing.

A gentler opinion refers to Jack’s situation as “a queer turn of the wheel.”

When Jack and his crew were arrested by the guards, one of their many fantastic claims was that they ran out of fuel during "a training exercise." If this had been the case, they would have been returned to service in UK.

However, the guards escorted them to the crash site where all could witness bullet holes in the fuselage. The evidence was clear. Thus, it was determined they had been returning from a military mission and could therefore be held prisoner.

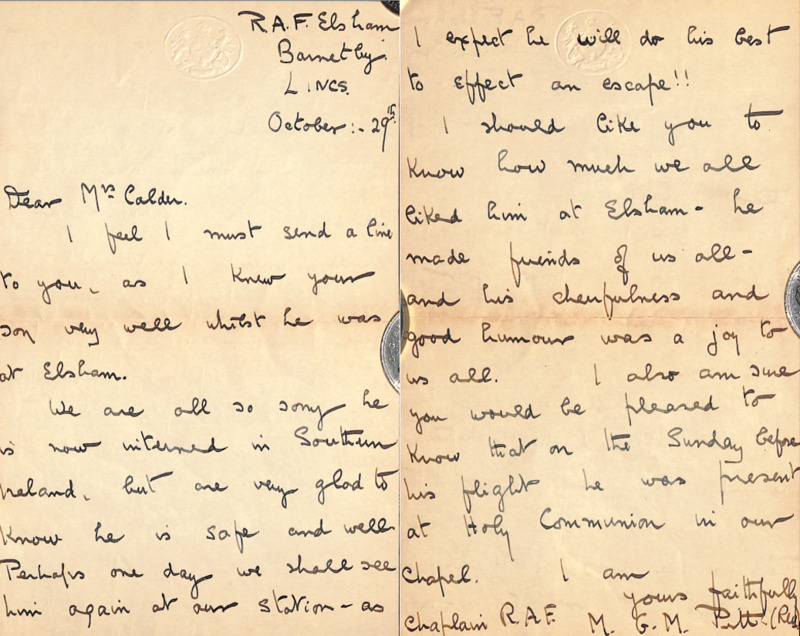

I also receive a letter from the chaplain stating that Jack made friends with everyone—“his cheerfulness and good humour was a joy” to them all, and he is sure Jack will do his best to effect an escape.

I don’t know what to hope for. He’s out of danger, for the moment; however, if he escapes, he’ll be thrown back into the fray.

Is it fair to pray that my son will be safe when so many others are fighting for their lives? I struggle to remain calm with these questions always in the back of my brain.

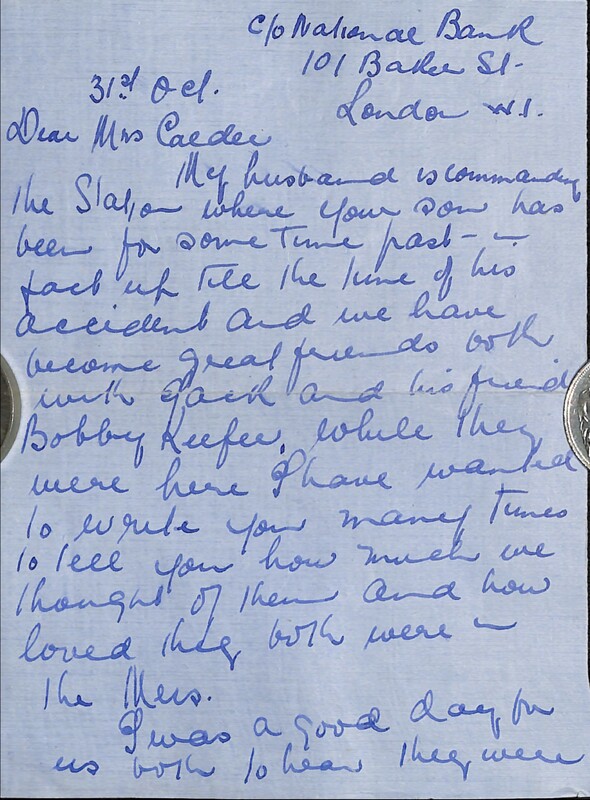

Finally, a lovely letter from Helen Constantine, the wife of the commander of Jack’s station, who states that she and her husband have become great friends with him and Bobby; she even shed many tears before news of their safety arrived.

She writes: “from every point of view Jack has been a tremendous success–so clever–so cool and brave–and always making a joke about the most difficult things.”

Well, that’s Jack to a tee. I must confess to feeling some jealousy. She writes as one mother to another, so kind of her, but I wish Jack were here in my dining room, laughing and joking.

Who knows when I shall see my boys again. I’m having a moment of sadness. This too shall pass. As Winston Churchill says, we carry on.

October 27, 1941

Archie receives a very kind letter from Senator Arthur Meighen. He and Archie knew each other when Archie was MLA for Chatham-Kent for two terms.

His good wishes for Jack include Jake and Philip, the only letter we have received so far that remembers we have three sons overseas.

October 29, 1941

Finally, a word from Jack himself. He only says, “Interned with Keefer. Everything okay.”

I want a letter.

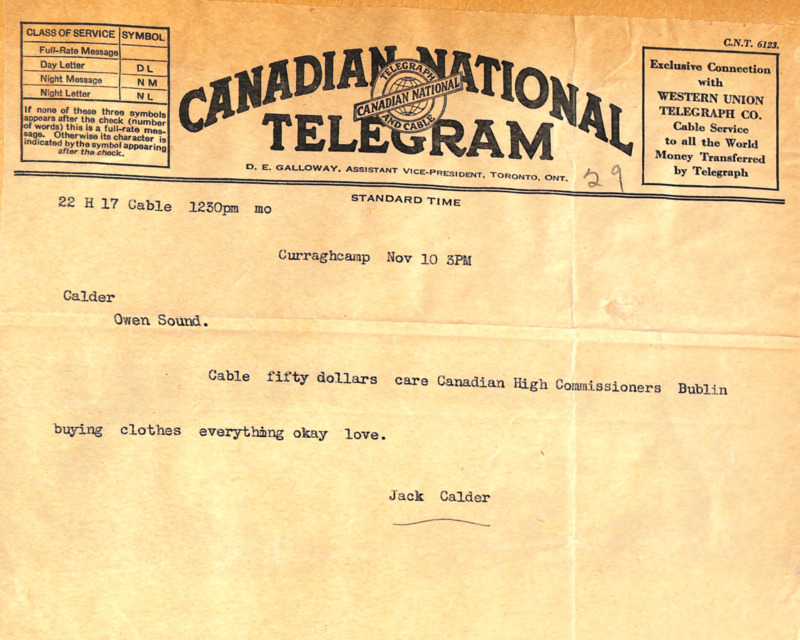

Another telegram from Jack. He is buying more civilian clothes. The Curragh prison has very liberal parole, possibly a political soft touch to appease the British who object to losing their highly trained RAF aircrew to the ridiculous neutrality policy. A curious blend of regulations has been agreed by the RAF and the Dublin government.

As I understand it, parole in Eire means that prisoners of both Allied and German sides may leave the Curragh daily to mix and mingle with locals but must return at night. During their outings they are pledged not to attempt escape.

At night, however, there’s a different story. The RAF requires prisoners to attempt escape by all means to return to their duties. They lead a sort of double life: during the day, pretending to be merely prisoners on parole, they are secretly seeking safe houses, using double-speak like spies to determine who is friend and who is foe; at night, they plot escape plans.

Civilian clothes will allow Jack to blend in, at least visually, with Irish folk. His red hair and freckles will be an asset, but should he escape, he’d better not open his mouth!

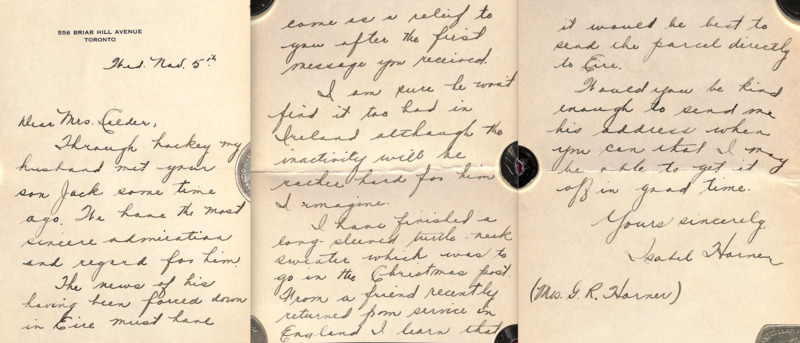

November 5, 1941

A surprise from Isabel Horner today. She has knitted Jack a long-sleeved turtle-neck sweater for Christmas. Isabel Horner is another person, unknown to his parents, who respects Jack. I suppose she met him at Maple Leaf Gardens. These letters from strangers are helping me build a more informed picture of my son’s life before the war, and his character through others’ eyes.

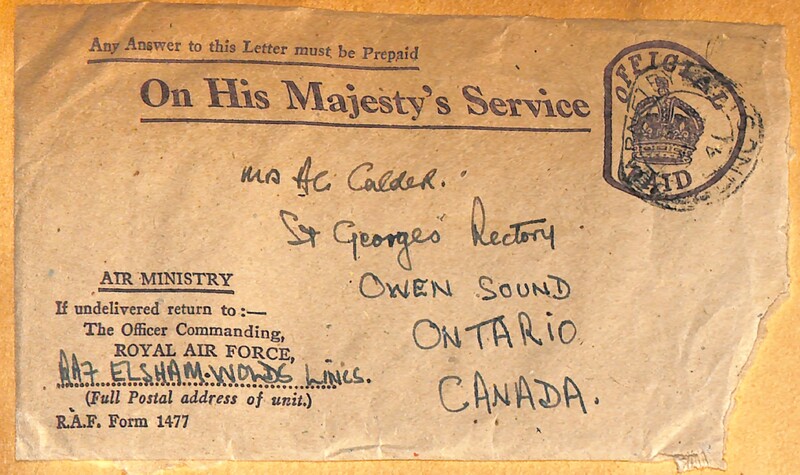

Oct. 29, 1941

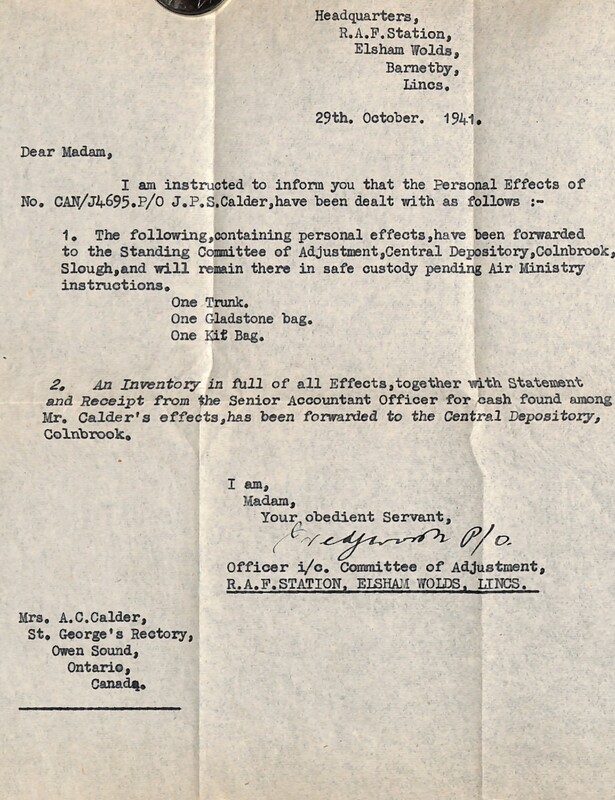

A number of very strange missives arrive this week. I’ve had messages from Headquarters because Jack is missing in action.

I've had a compassionate letter from the commanding officer of his squadron, claiming that Jack was his “best navigator.”

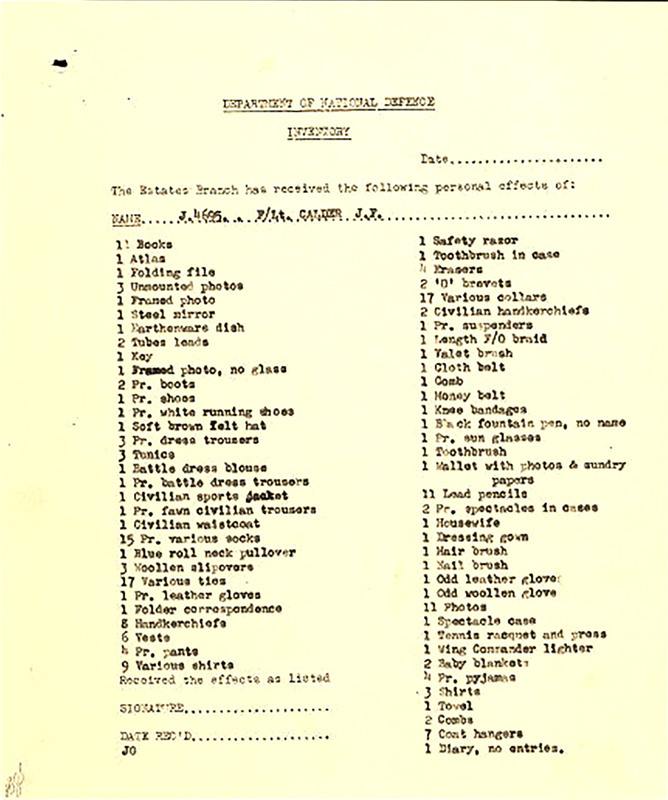

I've received a list of Jack’s belongings, as if he is already presumed dead.

August 4, 1942

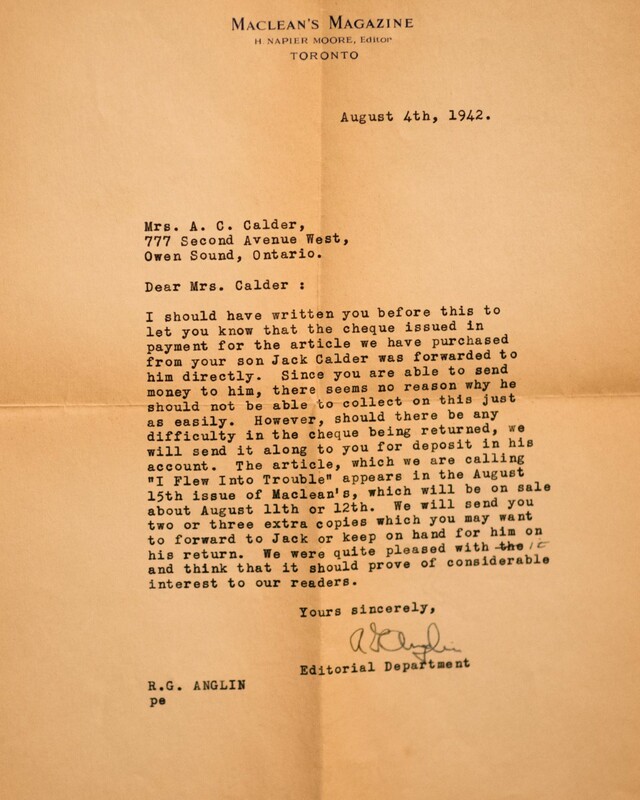

A letter arrives from the editor of Maclean’s magazine confirming that Jack will be paid for a story he wrote about his crash and subsequent arrest and internment in Eire.

This article has been widely circulated and is also receiving a great deal of attention on the radio. I am pleased at how Jack writes in a light-hearted voice, his dialogue reflecting the expressions of the local people, the whole story uplifting the reader with gentle humour and a positive outlook.

I frequently wonder at my own children’s intelligence and wit. Did they inherit these genes or were they grown in the healthy environment of western Ontario?

At last, I have received a letter from Jack. The parameters of his parole have widened from the immediate environs of prison to include Dublin. He sends two enclosures; one is a programme from the Gaiety Theatre in Dublin.

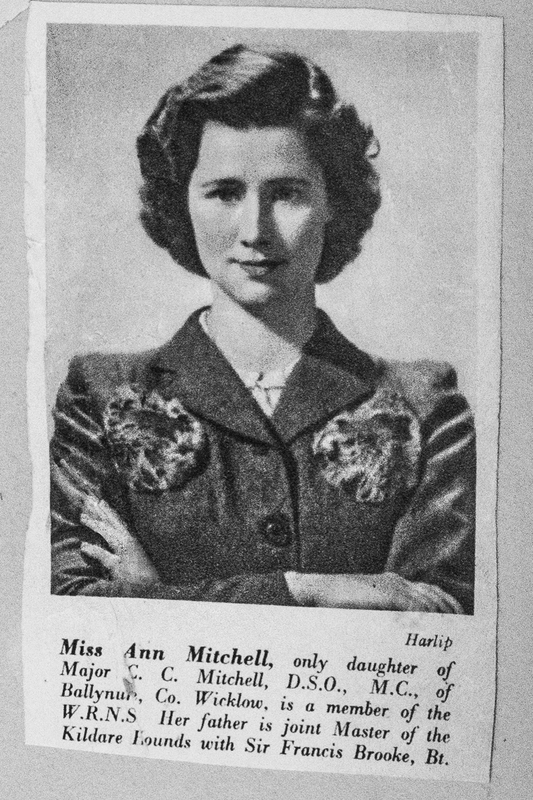

The other enclosure is a beautiful picture of a Miss Ann Mitchell of Ireland. This is the first time Jack has sent me a picture of a girl–she must mean something special to him. I see that she is a member of the WRNS; she travels to work in the UK.

He met Ann at a New Year’s Eve dance where she was wearing a long blue gown, his favourite colour. I think he is smitten.

Her father is involved in hunting. I’m guessing he’s one of the wealthy landowners known as horse Protestants who were given all the best land back in the 1700s. Jack says in his letter that Major Mitchell owns extensive stables and frequently attends the races. Archie wonders if the Major would be willing to provide a safe house if Jack escapes.

Ann Mitchell is a handsome woman, well-dressed and impeccably groomed. Her portrait is obviously a professional photograph. I must find a little silver frame and put her picture on the mantle with the rest of the family.

I bet I’ll soon be a mother-in-law. I wonder what she’s like. Jack always did have good taste in girls but so far he hasn’t been serious about any of them. The war makes young people think of love.

The prisoners occasionally work in the fields, fell trees, attend horse races, go riding, swimming, fishing, play football, rugby or soccer.

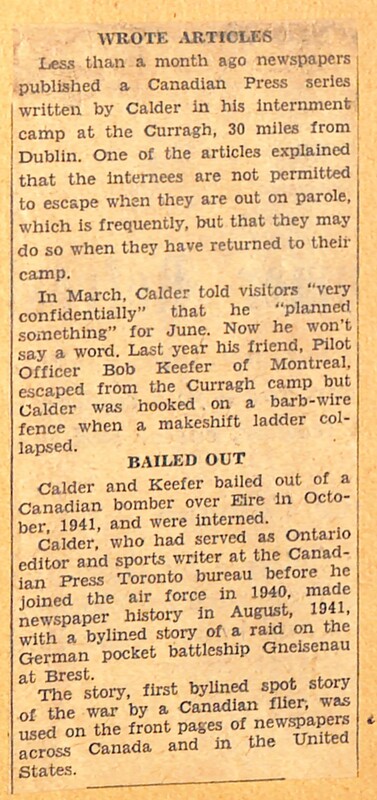

Jack feels it is a personal failure that his friends Grant Fleming and Bob Keefer escaped while he is left behind. I know he feels alone and despondent now. One day he’ll write about their escape: the home-made ladder, secret signals, the disguises, the chase by the guards. Since August, more barbed wire has been added to contain them.

The huts are raised to prevent tunnelling. However, now they've asked for a dog. The dog house hides their tunnel entrance. They disperse dirt slowly from their pants in trails around the compound.

The guards are handpicked from the IRA so they “know a thing or two about escaping.”

The Allied prisoners set off fireworks when Monty began his march into North Africa. The German prisoners have been silent lately.

The men long to return to ops. They want to be part of the final push that ends the war. As for me, I want him to be safe.

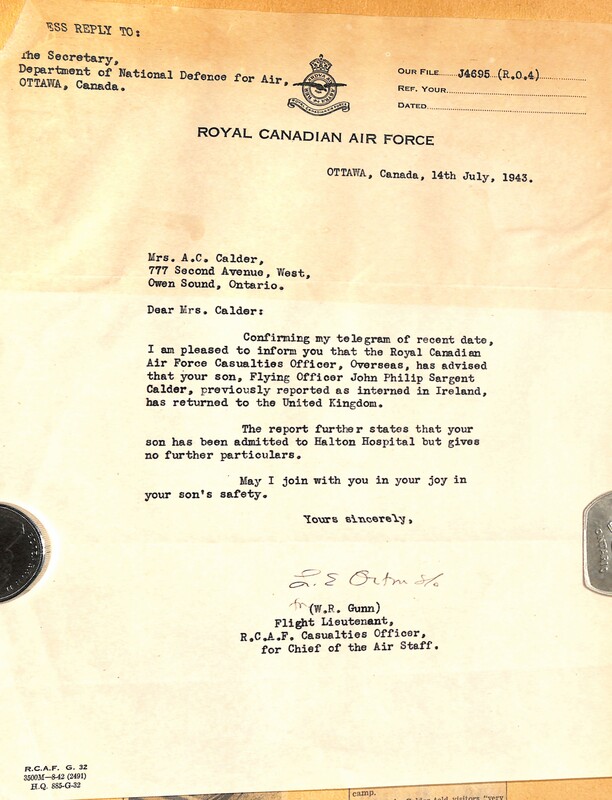

Jack is back in England. Nobody knows how. There’s a story waiting to be told but Jack is not permitted to say a word.

Jack escapes but refuses to tell the story? Not likely! Jack loves to hold an audience rapt with a good story. Something is rotten.

Apparently in March Jack told "visitors" very confidentially that he “planned something for June.”

One more line has leaked out about the night of Bobby Keefer’s escape. Now I know why Jack didn't escape with Bobby: his pants were hooked on barbed wire when the ladder collapsed.

CP is repeating reference to Jack’s story about the bombing of the Gneisenau: “first bylined spot story of the war by a Canadian flier…used on the front pages of newspapers across Canada and in the United States” “…made newspaper history.”

Archie receives a phone call from The Star wanting to know what the telegram said exactly and what was our reaction. “Surprised? I could hardly believe my eyes!” Archie tells them. "The telegram simply read: 'Pleased to inform you your son is safe in Great Britain.’”

Jack’s story is now being labelled “the classic internment case of the war.”

The mailman delivers another article: “Canadian Flier Got Away From Internment Camp.” It concludes with high praise for Jack’s series of articles which “give insight into conditions in Eire. Often his stories sparkled with Irish wit especially when telling how he visited the Eire parliament and various pubs.”

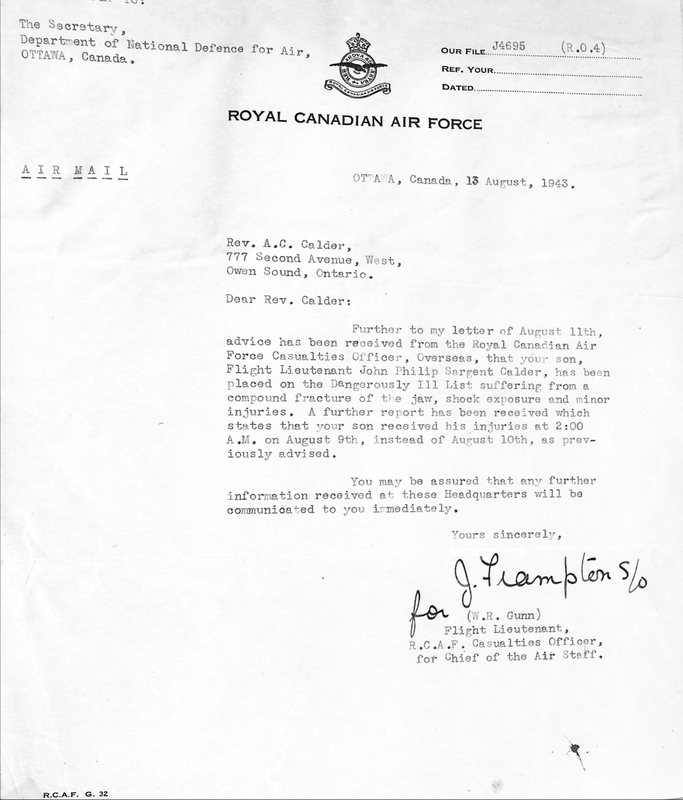

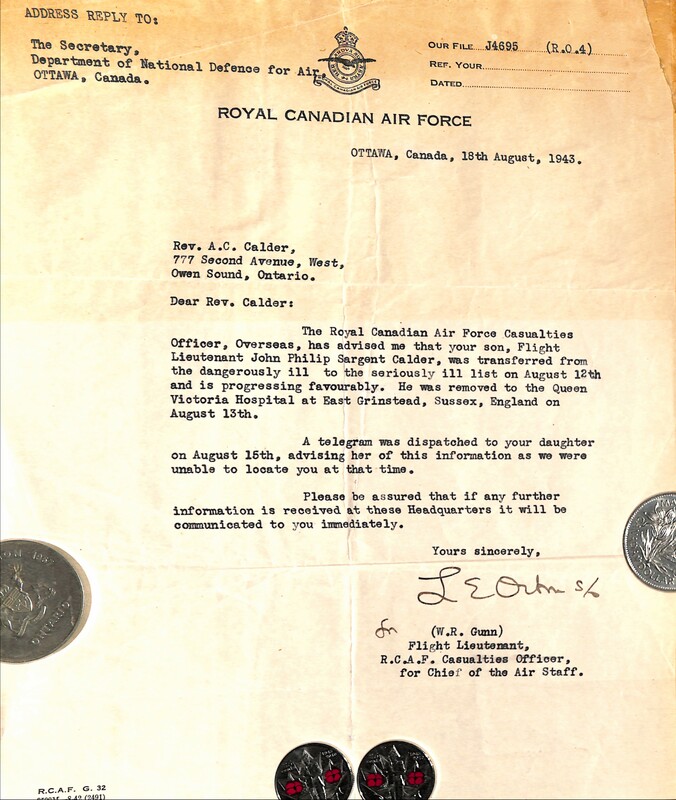

August 13, 1943

Would someone please tell us what happened? Where is Jack? Did he crash? Why is he “dangerously ill?”

August 18, 1943

We learn via telegram that Jack has been transferred from the dangerously ill to seriously ill list. He is moved to Queen Victoria Hospital at East Grinstead, Sussex on August 12.

Did his plane crash? Where?

We hear excellent reviews from parents of other patients who are treated at East Grinstead. It’s famous, “the spot to be if you’ve been in a crash.”

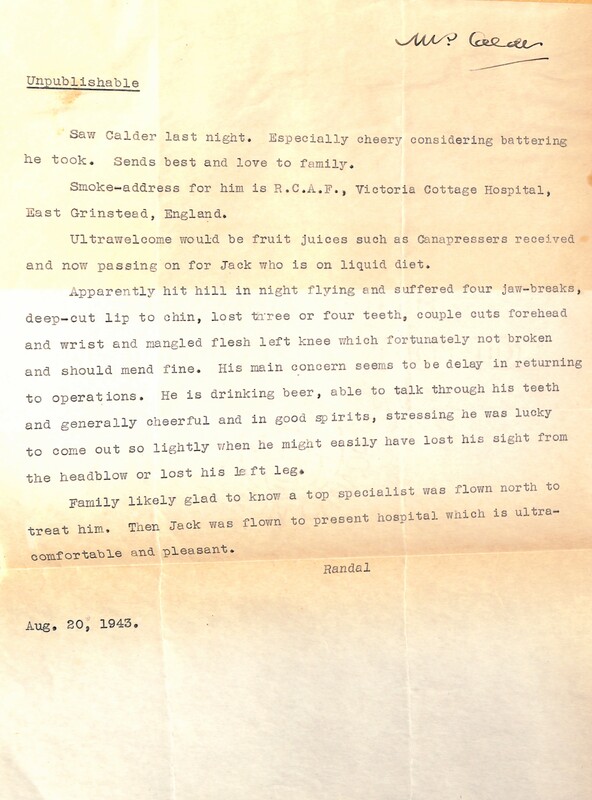

August 20, 1943

Thank Heaven someone from CP named Randal saw Jack in person and sends us a detailed report of his condition.

When we received the telegram that Jack was missing again, I feared the worst.

I’m glad I did not know the full extent of his injuries at the time. I might have lost my mind with worry about him.

I’ll invite the girls here for the weekend and we’ll put together a care package for Jack. We’ll make it fun to celebrate the fact that he has survived a second crash.

I don’t dare think about how many chances Lady Luck has in store for him.

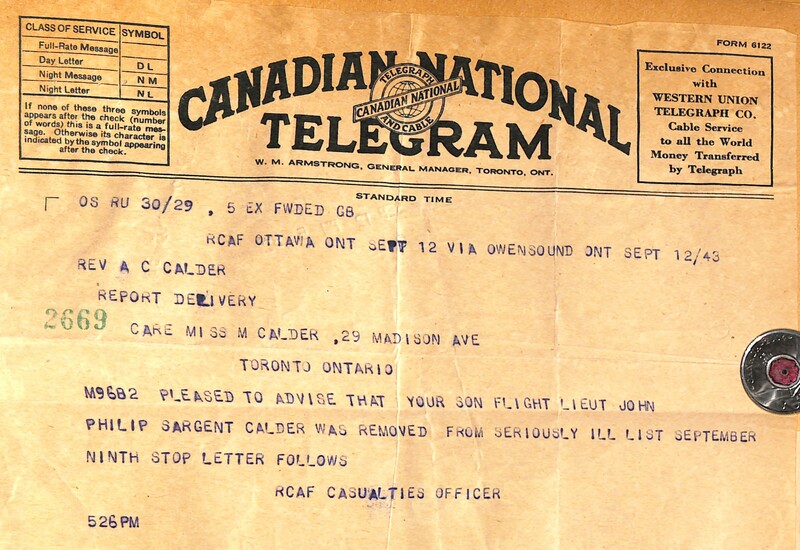

September 12, 1943

Jack has been removed from the seriously ill list.

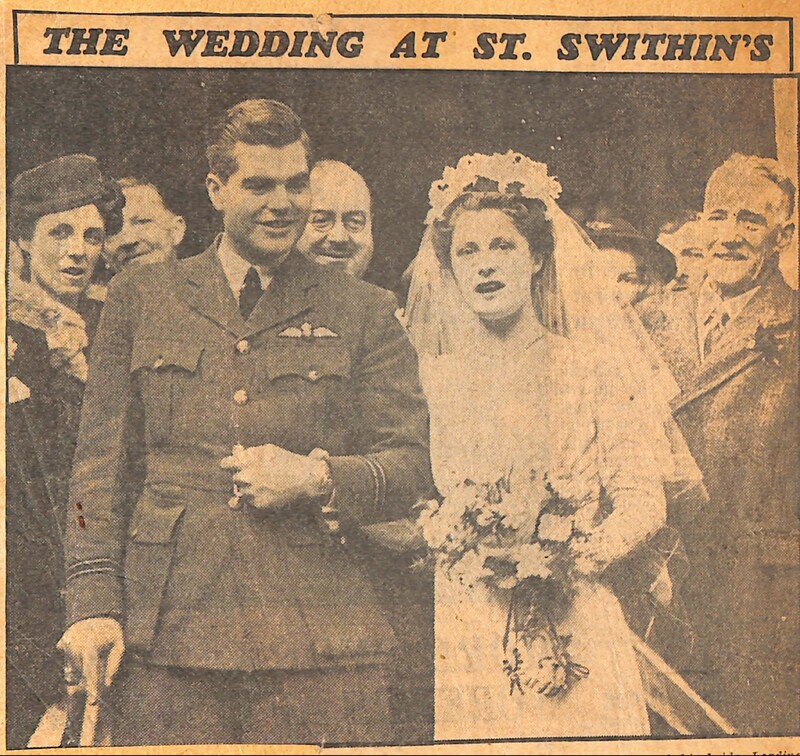

Jack has published a story about wounded Canadians and the care they receive. He weaves stories of the men he has met at Queen Victoria Hospital. I know he’s been too ill to write letters, but I’ve been greeting the mailman every day, hoping for news. Now I have a window into his life for the past eight months.

Jack sent me this story of a Flight Lieutenant, rescued from a dinghy after 14 days tossing in the North Sea, who watched two of his crew die before him. Then, young Betty Andrews nursed him back to health for 18 months, and, on their first date, escorted him out of a cinema moments before a bomb fell. To top it all off, the best man at their wedding was his anesthetist. The groom’s squadron flew fighter planes over the church in salute. How very Royal!

Yippee? I’ve never heard Jack say yippee in his life. He must really be celebrating no further knee surgeries. And he might be home on leave for a month? I’ll believe that when he walks through the front door.

My emotions are all in a turmoil. Why am I weeping?

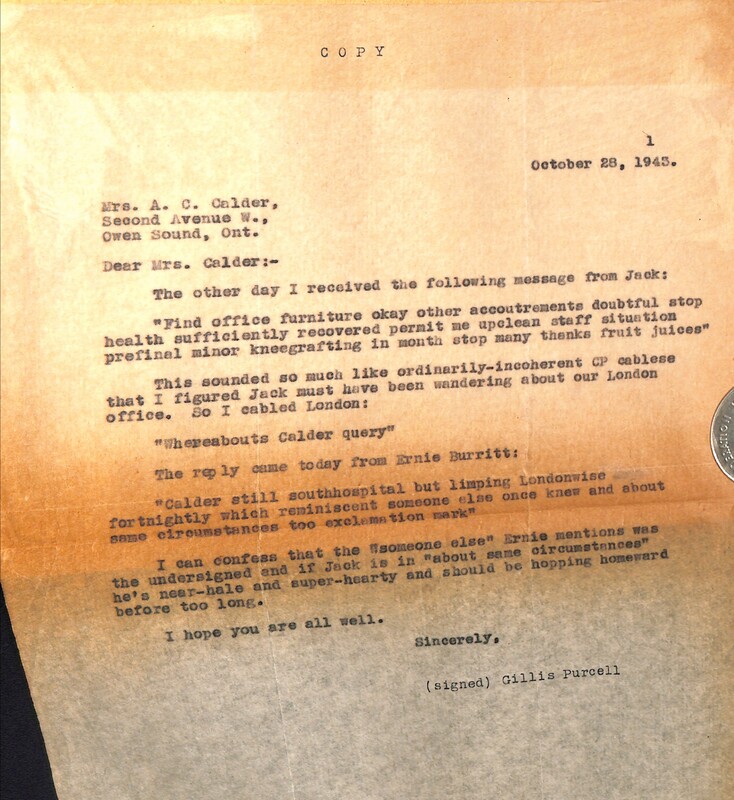

October 28, 1943

Gilles Purcell, chief editor of the London CP Bureau, sends me this crazy message to light a sparkle in my smile. The repartee between Jack and the other editors is delightful. Gilles reckons Jack is “near-hale and super-hearty and should be hopping homeward before too long.”

Best news I’ve heard all year.

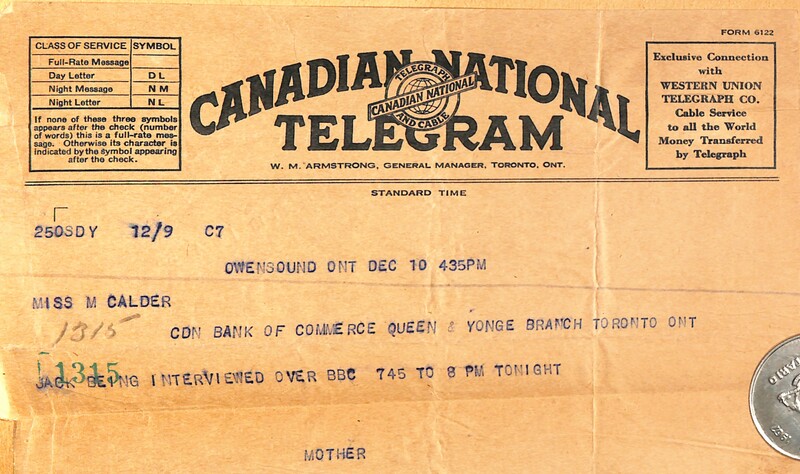

December 10, 1943

Jack is being interviewed over BBC tonight. Wow. That boy knows how to milk the career opportunities. He makes me laugh.

April 15, 1944

CB (probably Charles Bruce, editor-in-chief of the London CP Bureau) writes to Marjorie: "Jack was in town last night, looking exceptionally fit and full of that straight-faced kidding he is noted for. . . It was awfully good to see him again. Looks a bit older and slightly worn, which is only to be expected, but generally operating 100%.”

Hearing from someone who has seen Jack in person is the next best thing to seeing him for myself.

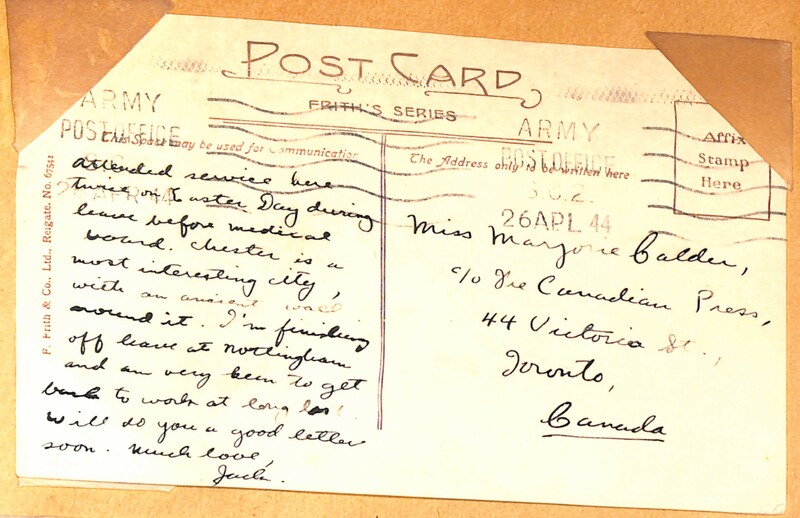

April 26, 1944

Marjorie has received a postcard from Jack. He is on leave and he’s been to church for Easter. Will visit Nottingham before appearing at Medical Board. Very anxious to be cleared to go back to work. Promises her a “good letter” soon.

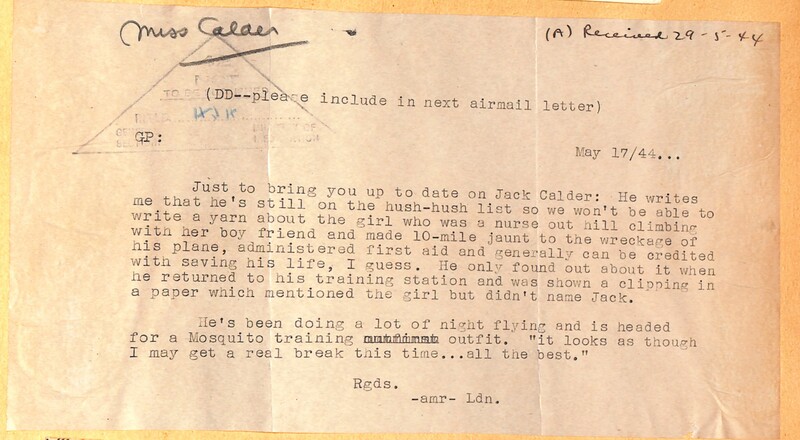

May 17, 1944

Marjorie has received a mysterious note about Jack. Jack is still not permitted to publish anything he writes, but his buddies at CP are leaking stories on his behalf. He nearly died in that night-time crash. He was rescued by a nurse who hiked with her boyfriend ten miles to the wreckage of his plane and can be credited with saving his life. I am reminded of the saying: “the truth will out.”

Jack is practicing night flying again and is headed for a Mosquito training outfit.

Ironically, he feels that he “may get a real break this time.”

May 31, 1944

Jack wrote me a letter with a picture of him in Dumfries. It's short and it looks like he scribbled it in a hurry. But it's a letter and it's in his handwriting.

June, 1944

This photo of Jack at Matlock, Derbyshire arrives today with a short message: "You see how well I have recovered. Ann and I took leave in Scotland, and on the way home, visited the site of my crash into Green Gable Hill where two of my crew died."

Sadly, too many lives are lost on training exercises. Three other Ansons from Jack’s unit crash in fog in the Lake District that same night.

I have been told that because Canadians learn to fly here in our big open skies, they’re not accustomed to flying in hills and low mountain ranges. In fog or low cloud, they cannot see where they’re going.

July 16, 1944

I have finally received a letter from Jack. He says, "Mom, a lot of the boys leave letters behind to be sent to their people if anything should happen to them. I never have written that sort of letter to you and never will. I feel quite strongly that I am not going to be killed." But he says, "I am very happy" and comments that if he should go "missing," then he would want me to think of him walking towards me, "for that," he says, "is what I would want to be doing. There is no death, you know."

I just want him home. And safe. With me.

Jack is missing again.

I can't breathe.

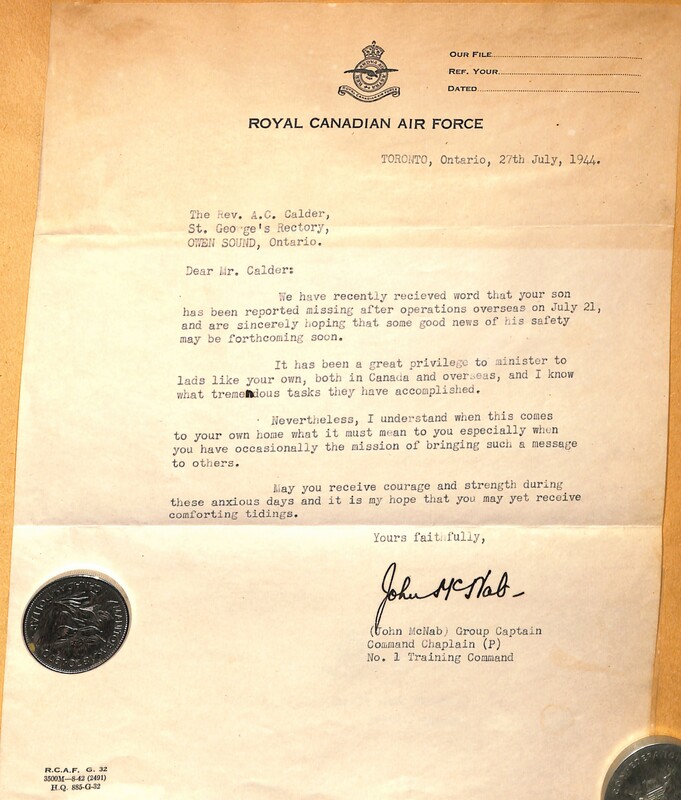

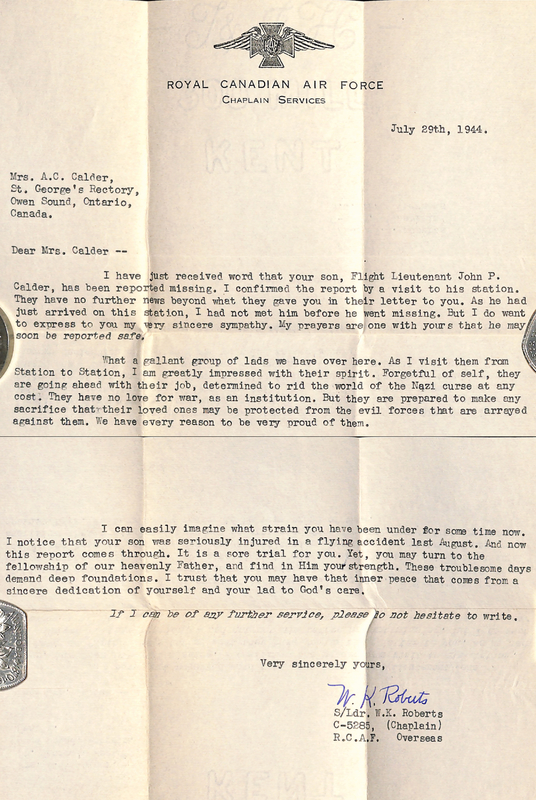

July 28, 1944

Our worst fears are confirmed.

Archie goes to St. George’s to conduct the Sunday service. It is too late to get a substitute and he thinks he should go. Nobody knows yet that we received the official letter.

When it’s time for Archie to deliver the sermon–which is meant to support those suffering loss–he is struck dumb. He stands in the pulpit for a few minutes, unable to open his mouth, and then steps down and exits the church by the side door.

Then everyone knows what we know.

Mary and Marjorie come home for a few days.

The first night the three of us sit in the covered porch and drink Irish whiskey. All the stories of Jack’s antics over the years float up. We laugh, and cry.

The second night we sit around the dining room table and sort all the newspaper clippings, telegrams, and memorabilia we have of Jack’s four years overseas.

The third night we glue the items into the scrapbook.

Every evening after supper Archie withdraws to the study.

His grief is private.

I shall have to write to Ann Mitchell.

I haven’t found the words.

One Wing Commander's lighter? Excuse me? What's the story, Jack?

I have written to ask if we may have Jack's letters and pictures from his trunk. No answer yet.

A dictionary. Even in war my son carried a dictionary. I remember Archie always kept a dictionary at the dining room table and liked to quiz the children on words as an after-dinner game.

At night I dream of my four boys.

Together. Laughing. Safe. Home.

Jack Calder Trophy: the Western Ontario Sports Writers Association, of which Jack was a member, put up the trophy for an annual award to the outstanding high school boy athlete in Western Ontario.

Post script

A year after Jack dies, his pilot, Dave Thompson, writes to tell us about Jack’s last moments in the air:

"The aircraft is a Mosquito de Havilland DH 98 B Mk XVI ML984, 571 Squadron.

"Jack and I are flying home from Hamburg when a German fighter plane latches onto our tail. In spite of repeated evasive action, I cannot shake it and the Mosquito is hit by flak. Jack moves into bombing position where he is wounded in both legs. From there he cannot reach his dinghy. By this time the ‘wooden wonder' is on fire so I order him to bail out because he should land in the sea close to land. I bail out immediately afterward.

“I survive in my dinghy for six hours during which time I see a Sunderland flying boat passing overhead but it does not see me to affect a rescue. After a German fishing boat picks me up, I become a POW.

"When the war ends, I walk to the English Channel and catch a boat back to Britain. All this time I donot know whether Jack is alive or not. I drop into the CP London Bureau to inquire and learn the news. Then I file my report at RCAF Headquarters."

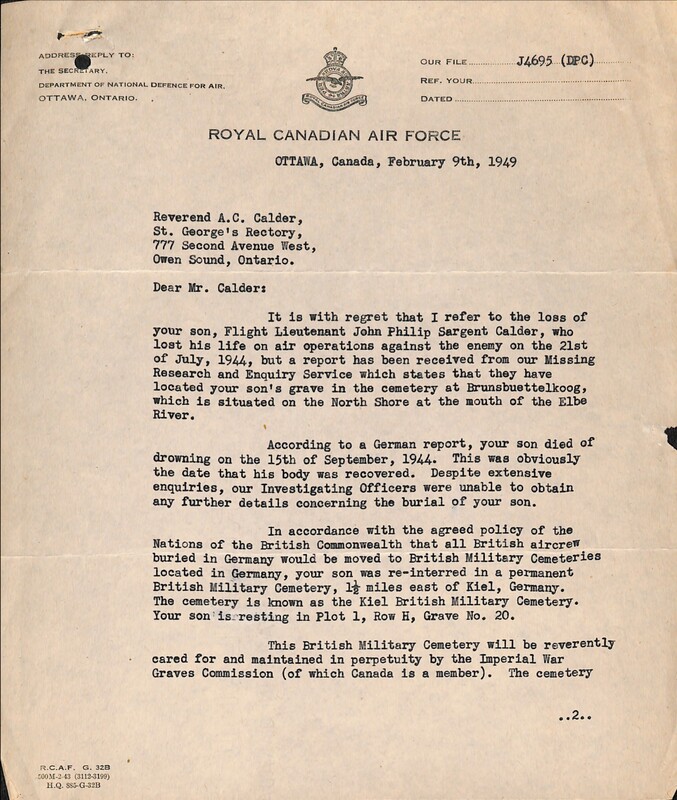

February 9, 1949

Four and a half years later, we are learning that Jack's body has been re-interred to a permanent cemetery near Kiel, Germany. The wound I though had healed is ripped open again.