1920s: Assumption Antagonism

Even with the achievement of Assumption’s fiftieth anniversary in May 1920, Bishop Fallon and Assumption College’s antagonistic relationship continued into the new decade [1].

Even after two years of affiliation with Western, almost all of Assumption’s college-level students were American, further upsetting Fallon, who wanted to encourage London students to enroll in Assumption’s programs [2]. Further adding to these tensions was the announcement in fall 1922 that the St. Mary’s Seminary in Detroit would add an arts course, creating additional competition with Assumption’s existing arts program that would diminish both Assumption’s number of students and steady source of tuition income [3]. At the same time, land that Assumption owned came up for sale, with a Mr. Marentette from Windsor offering the Basilians a significant sum of money in exchange for twelve acres of land along Huron Line, where the entrance to the Ambassador Bridge is located [4]. As the Basilians were desperate for cash, they were willing to potentially anger Fallon further by selling the land, so in April 1922, Muckle and the Basilian community offered Fallon $25,000 for Fallon to turn ownership of the land over to the Basilians, who could then negotiate with Marentette [5]. However, Fallon was extremely upset and took the matter to Rome in January 1923, signalling a future all-out confrontation rather than local negotiations [6].

In 1922, Forster had arranged the separation of Canadian Basilians from their French home base, creating a “new” religious community, the Basilian Fathers of Toronto, to which Forster was elected the Superior General of [7]. Forster convinced this community to accept “a simple vow of poverty with total dependence on a common life” rather than their current “qualified vow of poverty” that gave the Basilians a small salary [8]. This controversial provision led to Muckle asking to be relieved of his duties in November 1922, where he was replaced by Father Daniel Dillon, who, despite initial hesitation, “turned out to be a superb choice, the kind of hard-nosed administrator the College needed if it were to outlive the crisis that was about to erupt" [9].

Due to the new provisions, four of Assumption’s professors, including Father Charles E. Coughlin, left to join the Diocese of Detroit, leaving Assumption severely depleted and giving an opportunity for Fallon to flex his power over the College [10]. Coughlin had taught at Assumption College since 1916, but after Forster’s policy change, Coughlin left to join the Archdiocese of Detroit, where he constructed the grand Shrine of the Little Flower and where he began his religious radio broadcasts that received wide acclaim and success throughout the Midwestern US [11]. Later known as the “radio priest,” Coughlin’s broadcasts evolved to become bastions of anti-Semitism, along with anti-union and both anti-Communist and anti-capitalist rhetoric, that played upon fears of the American people and turned himself into a political powerhouse that could ruin careers with a mention on his broadcasts [12]. However, Coughlin’s increasing anti-Semitic and pro-Nazi rhetoric resulted in backlash from the Detroit Archbishop, Edward Mooney, who, under pressure from the American National Association of Broadcasters, forced Coughlin to end his radio broadcasts and stop printing his companion magazine, Social Justice, leaving him as the pastor of his church until his retirement and death in 1979 [13]. While Coughlin’s tenure at Assumption preceded his public expressions of anti-Semitism, Coughlin, much like Frachon in the 1850s, represents a darker element of Assumption’s history. But in the 1920s, the loss of four of Assumption’s best professors to Detroit gave Fallon an opportunity to force the transfer of the Arts Department to Western. As the school’s annual operating costs were $180,000, requiring 200 boarders on campus, if Fallon was able to go through with his plan to move the Arts Department to London, Assumption would see a deficit from $10,000 to $20,000 per year, which would force this historic school to close [14].

In response to the loss of a significant portion of Assumption’s faculty, Fallon contacted the Basilian vicar-general with rumors that “a considerable number of your members intend to leave your community,” highlighting that these events could embarrass the Basilian community [15]. Fallon then commented to London newspapers about the plans to build two new colleges at Western, Brescia College and Assumption College, which was news he had not shared with the Basilians [16]. To add to the pressure, Fallon gave Dillon an ultimatum in April 1923, stating that Assumption “had not lived up to their end of the bargain” in regards to affiliation with Western, contrasting the Ursulines that had affiliated and started construction on a new building in London, giving Dillon a deadline of June 1, 1923 to respond and threatening to open university courses for Western students if he wasn’t satisfied with their response [17]. Fallon received a forceful response from Dillon that stated only the Basilian superior general and the council could decide what to do with the Arts Department, but this Basilian council missed Fallon’s deadline to respond [18]. In response to Fallon’s increasing challenges to his former school, Forster outlined “his reasons against a transfer in 1923 or at any time in the foreseeable future,” where he emphasized how this transfer would cause severe financial harm to Assumption with the loss of a significant amount of its student body and that the Basilians did not have the finances required to construct a new building on Western’s campus [19].

Fallon responded to Assumption’s continued reluctance with “the biggest weapon in his arsenal” on September 1, 1923: placing the community of the College under interdiction, which prevented any member of the community to administer sacraments while in Fallon’s diocese [20]. This drastic action forced the Basilians to appeal to the Vatican in Rome for what they believed was Fallon’s spite against them [21]. After reviewing the situation, the Vatican ruled that the Basilians were not allowed to sell the land without Fallon’s permission and that Fallon had a right to establish a three-year Arts course in London, decisions that greatly affected Assumption’s ability to retain students and make enough money to keep its doors open [22]. However, the Vatican also ruled that Fallon “had no right to impose interdiction” and that the Basilians “had every right to maintain their parish” in Sandwich [23]. McMahon states that if Assumption had moved to Western’s campus, giving into Fallon’s demands, “post-secondary education in the Sandwich/Windsor area would have come to an end,” thereby altering the history of Windsor and its inhabitants [24].

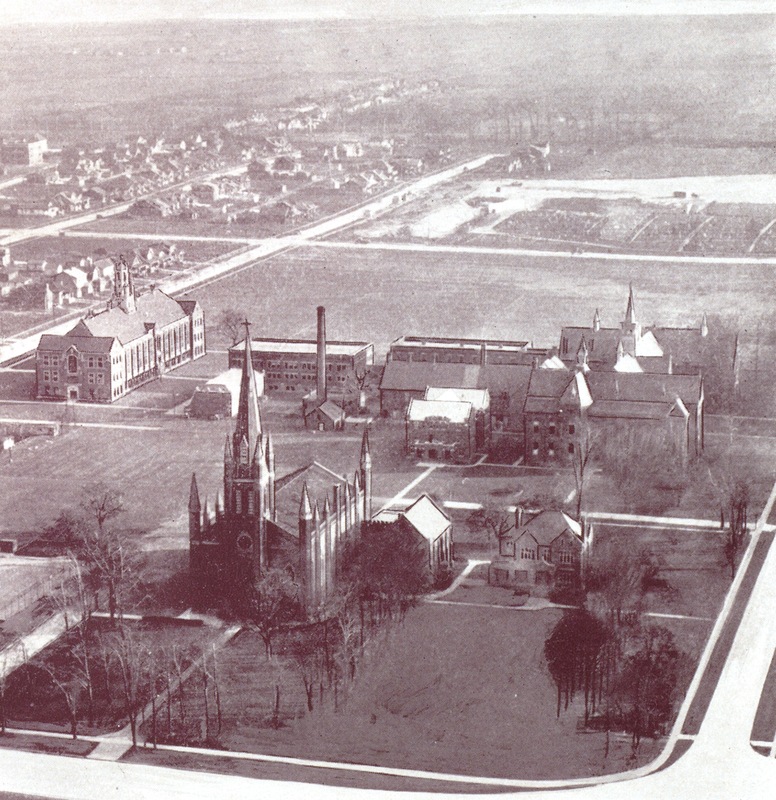

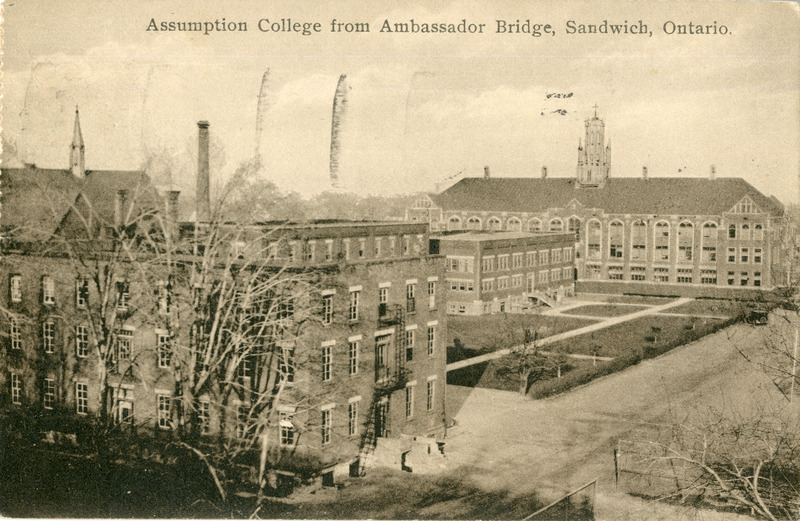

After the debacle with Fallon, Assumption was concerned with internal affairs to ensure that it could take in enough students to continue operating. Dillon’s main concern in the 1925 school year was the start of negotiations to build a bridge to connect Windsor to Detroit, which would be located close to the campus, creating fears that “prospective patrons [would] be unfavourably impressed with the location of the College” [25]. With the construction of the bridge, the Canadian Transit Company negotiated with the Basilians (and, due to the Vatican’s ruling, with Forster as well) to purchase 15.3 acres of Basilian land, with the sale giving Assumption some financial breathing room [26]. Additional concerns about inadequate ventilation and general disrepair resulted in plans for the construction of a new building in December 1926 at the cost of $250,000 (today at the cost of well over $3,500,000) [27]. This building would eventually be named Dillon Hall after Assumption’s sixth superior [28]. Dillon Hall was used by both the high school and college until the “new” Assumption High School was built on Huron Church Road in 1957 [29].

Father Vincent Kennedy took over from Dillon in 1928, who was perceived as “more a scholar than an administrator,” but was able to achieve several accomplishments during his short term from 1928-1931 [30]. Kennedy established better relations with Fallon, including an agreement for all future land sales that would give 1/3 of the profits to the London diocese and 2/3 to the Basilians and an agreement to sell the front area of campus (from former London Street, now University Avenue, to the river) to the Sandwich Parks Commission [31]. Just after his arrival, Kennedy began planning for methods to expand Assumption’s student body and reputation, including the introduction of an M.A. program in Philosophy, a pre-medicine program, and Extension part-time evening courses for adult students, mainly elementary school teachers, that would be open to secular and non-secular students as well as women [32]. While graduate programs at Assumption were established in the 1930s, the discussion of Extension courses with the education of women by religious men and having non-Catholic students in Catholic schools ended in 1929 with Forster’s final dismissal of the proposal shortly before his tragic accidental drowning on November 11, 1929 [33]. Similarly, Kennedy’s plans to modernize Assumption’s education system with a pre-medicine program failed due to the financial expenditure required, as the Wall Street Crash of 1929 only exacerbated existing problems [34].

Despite the calamity of the negotiations with Bishop Fallon, Assumption managed to weather the tumultuous 20s and emerge more well-equipped to deal with future crises, with an expanded campus, financial plans, and the framework for a more diverse student body. However, Assumption’s continued financial problems were only exacerbated by the Great Depression, and with Kennedy’s departure in 1931 due to ill health, Assumption needed a strong leader to see it through the 1930s [35].

[1] Power, “Fallon Versus Forster,” 57.

[2] Power, “Fallon Versus Forster,” 57.

[3] Power, “Fallon Versus Forster,” 57.

[4] Power, “Fallon Versus Forster,” 57.

[5] Power, “Fallon Versus Forster,” 57.

[6] Power, “Fallon Versus Forster,” 57.

[7] Power, “Fallon Versus Forster,” 58.

[8] Power, “Fallon Versus Forster,” 58.

[9] Power, “Fallon Versus Forster,” 58-59.

[10] Power, “Fallon Versus Forster,” 58.

[11] “A Historical Exploration of Father Charles E. Coughlin’s Influence,” University of Detroit Mercy, https://libraries.udmercy.edu/archives/special-collections/index.php?collectionSet=community&collectionCode=coughlin_cou&page=2.

[12] Albin Krebs, “Charles Coughlin, 30’s ‘Radio Priest,’ Dies,” New York Times, 28 October 1979, 44. https://www.nytimes.com/1979/10/28/archives/charles-coughlin-30s-radio-priest-dies-fiery-sermons-stirred-furor.html.

[13] “A Historical Exploration of Father Charles E. Coughlin’s Influence.” University of Detroit Mercy. https://libraries.udmercy.edu/archives/special-collections/index.php?collectionSet=community&collectionCode=coughlin_cou&page=2; Krebs. “Charles Coughlin,” New York Times, 28 October 1979, 44. https://www.nytimes.com/1979/10/28/archives/charles-coughlin-30s-radio-priest-dies-fiery-sermons-stirred-furor.html.

[14] Kelly, 46.

[15] Power, “Fallon Versus Forster,” 59.

[16] Power, “Fallon Versus Forster,” 59.

[17] Power, “Fallon Versus Forster,” 60.

[18] Power, “Fallon Versus Forster,” 61.

[19] Power, “Fallon Versus Forster,” 61.

[20] McMahon, 21.

[21] McMahon, 22.

[22] McMahon, 22.

[23] McMahon, 22.

[24] McMahon, 22.

[25] Kelly, 51.

[26] Kelly, 53.

[27] Kelly, 51-53.

[28] Kelly, 51-53.

[29] Kelly, 51-53; McMahon, 43; Ian Webster, “CPI Inflation Calculator: 1926,” In 2013 Dollars.com, 2021. https://www.in2013dollars.com/canada/inflation/1926?amount=250000.

[30] McMahon, 61-62.

[31] McMahon, 62.

[32] McMahon, 65; 67.

[33] McMahon, 66; 71-72.

[34] McMahon, 72; 74.

[35] McMahon, 83; 85.