1860s: Rumor, Ruin, and Raids

The close of the 1850s saw the appointment of Malbos’ successor, Father Clement Frachon, whose tenure would result in the “costliest mistake” of Pinsonnault’s administration of Assumption College [1]. In April 1860, both the Detroit Free Press and Toronto’s The Globe reported on Frachon’s sudden disappearance from Assumption and suspicion that he had absconded to Louisville, Kentucky, with a significant portion of the college’s funds, estimated around $1,000 which today would amount to well over $31,000 [2]. Frachon’s letter to Bishop Pinsonnault stated that he had taken $60 for travel expenses and “coolly requested” that his books be accepted as compensation for this additional theft [3]. In addition to this scandal, rumors abounded that Frachon had taken “improper liberties” with female servants as Assumption, aligning with the discharge of all women from the college, raising questions if these were simply rumors or had aspects of truth [4]. With Frachon’s only achievement to obtain funding from the Legislature, giving Assumption steadily increasing funding till 1868, Frachon and the College were disgraced, resulting in the college’s indefinite closure in the wake of this event [5].

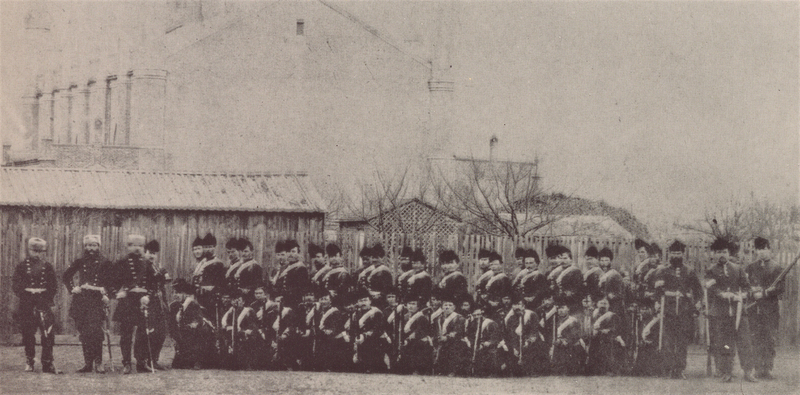

In the aftermath of Frachon’s disgraceful tenure, in September 1857, Bishop Pinsonnault negotiated an agreement with the Benedictines of Pennsylvania to take over administration of the College [6]. The first group of the German-speaking Benedictines arrived in Sandwich later that month, led by Father Oswald Moosmueller, but had left by April 1863 due to financial problems and issues with Bishop Pinsonnault [7]. While the Benedictines gave the College some semblance of stability and legitimacy, their problems with the French elements of Sandwich and Pinsonnault’s overbearing nature resulted in yet another disaster for Assumption College [8]. To add onto these issues, international events brought further turmoil to the College, threatening to upend its already shaky foundations. By February 1864, with fears of Fenian raids to pressure for Irish independence from Britain, multiple companies of troops were quartered at Assumption College to prevent against further incursions across the border [9]. With the end of the American Civil War in 1865, Fenians organized Confederate sympathizers in the northern United States near the border, resulting in additional garrisons of British troops at Assumption College in 1866 to protect the Sandwich area [10]. While no real Fenian threats ever materialized in Sandwich, the fear of such threats was palpable. Impromptu civilian militias, emboldened by exaggerated and false news of Fenian raids, patrolled Sandwich day and night, ready to respond to any potential threats [11]. In one of many similar incidents, a cross-border ferry called the Union was spotted going further down the river and closer to the Canadian shore than usual, which sparked fear of Fenian invaders who were planning to land, resulting in a large force of troops, local militia, and townspeople that, once news travelled through that it was a false alarm, “must have appeared rather ludicrous” [12]. Events such as these demonstrate the tensions that existed in Sandwich at the time, which, with multiple garrisons of troops stationed there, must have affected both the students and staff of Assumption College. Despite this period of disorder from both local and international concerns, Monsieur Théodule Girardot, who had been the first instructor of the College since its opening in 1857, continued to maintain Assumption’s common school, thus ensuring some semblance of continuity during chaotic times and establishing a pattern of laymen who would serve Assumption College and allow it to thrive in spite of upheaval that would continue to haunt it [13].

In the absence of Benedictine support at Assumption College, Father Pierre Dominic Laurent of the Sandwich diocese took over as administrator and achieved much success, increasing student enrollment to 52 boarders by 1870 [14]. As he had practically saved the College from extinction after its disastrous early 1860s, Laurent came into conflict with Bishop John Walsh, the second bishop of the London diocese, who sought different plans for Assumption. In 1868, Bishop Walsh saw the benefit if both Assumption’s parish and College were under the care of a religious congregation, and thus began negotiations with the Basilians of Toronto so they would resume control of Assumption [15]. As Walsh had seen the success of St. Michael’s College in Toronto, a Basilian college, and didn’t want to “repeat [what he believed were] the Machiavellian tactics” of previous presidents, he felt that Basilian control of Assumption would benefit the parish, school, and community, despite Laurent’s opposition to such a plan [16]. Father Jean Mathieu Soulerin, the Fourth Superior General of the Basilians, selected a young Father Denis O’Connor to oversee the negotiations with Bishop Walsh for the fate of Assumption College and to oversee the administration of St. Michael’s College on account of his administrative experience at St. Michael’s, which would serve him well in his later responsibilities at Assumption [17]. As a result of their negotiations, the Basilians were given the College buildings along with 80 acres of land south of it, while Walsh assumed all debts and a collection taken up in London diocese to repair the College buildings, and any government grants possible would be given to the College [18]. In return, the Basilians would assume responsibility for the church and parish, and would re-open the College with “classical and commercial course of studies” based off of St. Michael’s College [19]. However, the Basilians would have the responsibility to ensure they maintained sufficient staff members to operate, and would teach, at their own cost, two to three students personally selected by the Bishop [20]. All of these criteria would have to be met within two years of the College’s reopening [21]. With these high standards, the Basilians were given an out: Walsh stated that the congregation could withdraw from the “Sandwich College” if operating it proved too costly or difficult [22]. The resumption of Basilian control of Assumption College proved to be a new chapter in its history, one that would see some of its greatest successes.

[1] McMahon, 4.

[2] “An Absconding Priest,” The Globe (1844-1936), 11 April 1860, 2; Ian Webster, “CPI Inflation Calculator: 1860,” In 2013 Dollars.com, 2021. https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1860?amount=1000.

[3] “An Absconding Priest,” The Globe (1844-1936), 11 April 1860, 2.

[4] “An Absconding Priest,” The Globe (1844-1936), 11 April 1860, 2.

[5] McMahon, 4.

[6] McMahon, 4.

[7] McMahon, 4.

[8] McMahon, 4.

[9] “Earadian Items,” Detroit Free Press (1858-1922), 4 February 1864, 3; John R. Grodzinski and Peter Vronsky, “Fenian Raids,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, 5 June 2020. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/fenian-raids#.

[10] Grodzinski and Vronsky, “Fenian Raids,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, 5 June 2020. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/fenian-raids#; “British Troops on Assumption Campus During the Fenian Raids,” Assumption High School Yearbook 1949-1950, Southwestern Ontario Digital Archive (SWODA), 20. http://swoda.uwindsor.ca/node/3622.

[11] William H. Aston, History of the 21st Regiment, Essex Fusiliers, of Windsor, Ontario, Canadian Militia: With a Brief History of the Essex Frontier, the War of 1812, Canadian Rebellion of 1837, Fenian Raids, War in South Africa, etc., Including an Account of the Different Actions in Which the Militia of Essex Have Been Engaged (Windsor: William H. Aston, 1902), 85. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.9_90155/80?r=0&s=1.

[12] Aston, History of the 21st Regiment, Essex Fusiliers, of Windsor, Ontario, Canadian Militia, 89. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.9_90155/80?r=0&s=1.

[13] McMahon, 5; Kelly, 3; “Heritage,” Assumption University, 2016. http://www.assumptionu.ca/about-us/history/.

[14] McMahon, 5.

[15] Roach, 24.

[16] McMahon, 4-6.

[17] McMahon, 6-7.

[18] McMahon, 8.

[19] McMahon, 8.

[20] McMahon, 8.

[21] McMahon, 8.

[22] McMahon, 8.