Henry and Mary Bibb

By Irene Moore Davis (2020)

In the Underground Railroad era, Sandwich was not only a magnet for freedom seekers. It was also an appealing destination for abolitionists: rather than being harassed or actually endangered by pro-slavery forces in the United States, these individuals could now carry on their anti-slavery work in relative safety while still being in close enough proximity to like-minded American activists, organizations, and sources of funding… and they could be on the ground, helping the Black refugees at their time of greatest need, immediately following their arrival in Canada.

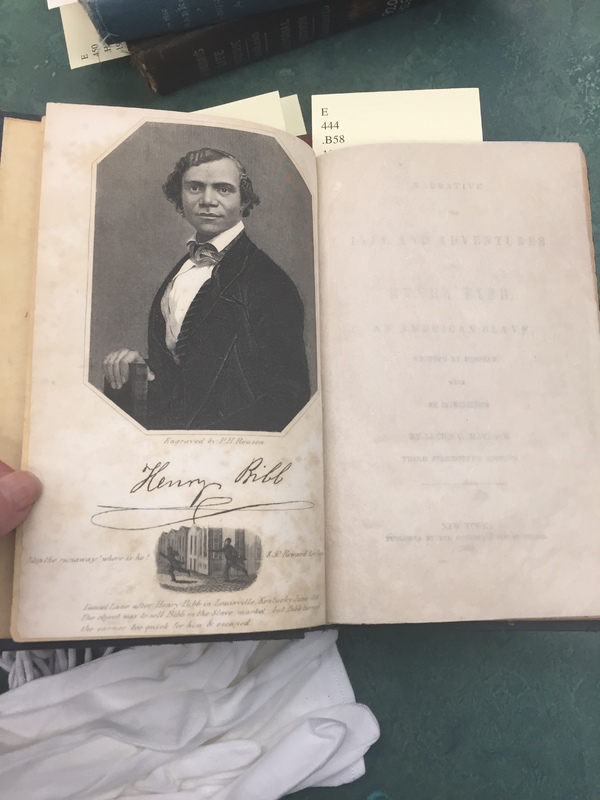

The most notable (but by no means the only) example was a remarkable couple, Henry and Mary Bibb. Born in 1815, Henry Bibb had been enslaved in Kentucky, Louisiana, and Texas, escaping slavery, being recaptured, and escaping slavery again before becoming a respected anti-slavery orator and writer. His wife, Mary Miles Bibb, was a teacher who had been born a free person of colour in Rhode Island in 1820. By the time they arrived in Sandwich in 1850, they were already well established members of the abolitionist movement. They had met through the movement and were married in 1848.

Henry Bibb wrote in his 1849 autobiography, Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb, An American Slave, Written by Himself, that he had been thinking about Canada for some time. Even while enslaved in Kentucky, he heard that “Canada was a land of liberty, somewhere in the North.” The fact that he published such an autobiography in the United States while his slave-owner was still looking for him is a testament to his courage and commitment to anti-slavery efforts.

With the passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, the Bibbs felt compelled to seek greater security in Canada. Along with Henry’s mother, Mildred Jackson, whom he had brought north to freedom in 1845, the Bibbs chose Sandwich as their new home. Observing that Black children and adults had no access to the schools in Sandwich, Mary Miles Bibb opened her own school and taught day and evening classes without pay for over a year. While the conditions of the school were far from ideal, she was able to secure donations from abolitionist philanthropists in Michigan to obtain a chalkboard, books, and other needed supplies. She then earned money through a dressmaking business. At their home in Sandwich, the Bibbs offered food, clothing, shelter, and other supports to newly arrived Black refugees; sometimes, they received freedom seekers right on the shore of the Detroit River. One day in 1852, Henry received three of his own brothers at the end of their Underground Railroad journey, with joy and relief.

In November of 1850, Henry organized and chaired the Sandwich Colored Convention, where he convinced the delegates to pass a resolution to establish a newspaper to advocate for Blacks in Canada West. The Bibbs wasted no time and published the first issue of The Voice of the Fugitive in Sandwich on January 1, 1851. Their newspaper garnered support for the anti-slavery movement, provided tips for Blacks who were interested in emigrating to Canada West, and told stories of both success and hardship, the latter with the hope of raising funds and awareness around the Black refugees’ experiences. Both Henry and Mary were involved in writing and editing. So, too, was James Theodore Holly, another young Black star of the anti-slavery movement who had moved to Sandwich with his wife, Charlotte.

The Bibbs also took responsibility for managing the Refugee Home Society and administering its funds. They were not the founders of the Refugee Home Society: it had been established in 1851 by abolitionists in Ontario and Michigan. The Society raised funds in the United States and Canada to purchase land which could be resold to formerly enslaved families with low rates and favourable terms and conditions, and to provide refugees with tools, supplies, training, and protection from slave catchers so that they could become successful farmers. Settlements were created in Sandwich and Maidstone Townships, totaling approximately 2,000 acres. Many descendants of Refugee Home Society settlers continue to live in the region today.

In 1852, the Bibbs moved from Sandwich to Windsor, where Mary opened a new school which was open to both Black and white students. This time, she received financial support from the American Missionary Association. At one point in 1853, she reported that she was teaching sixty nine students. Over and above all of their other efforts, the Bibbs went on to establish the Windsor Anti-Slavery Society.

Tragically, Henry Bibb died on August 1st, 1854 at the age of thirty nine. Widowed at the age of thirty four, Mary Miles Bibb continued working as a schoolteacher. Eventually, she married Isaac N. Cary. From 1865 until 1871, she operated a store in Windsor. When her second husband died, she relocated to Brooklyn, New York, where she remained until her death in 1877.

Henry and Mary Bibb have been designated Persons of National Historic Significance by the Government of Canada. Their federal heritage plaque can be found on Sandwich Street, adjacent to Mackenzie Hall.